Political Advocacy in Occupational Therapy: A Professional Imperative

Table of Contents

Abstract

BACKGROUND: Despite Occupational Therapy (OT) practice growing more political, practitioners lack awareness of the impact of current policies on services. Low advocacy levels among practitioners may stem from inconsistent definitions of advocacy and a lack of guidance on effective advocacy.

OBJECTIVE: To explore the meanings of and participation in political advocacy by OT practitioners and students.

METHODS: This qualitative, descriptive study used in-depth, audio-taped telephone interviews to explore participants’ perceptions of political advocacy in OT. The study utilized convenience sampling of 13 occupational therapy practitioners and students recruited from two local OT professional events. Participants defined the term ‘political advocacy’ and shared their participation in political advocacy activities. Concept mapping and thematic analysis were used to analyze the data.

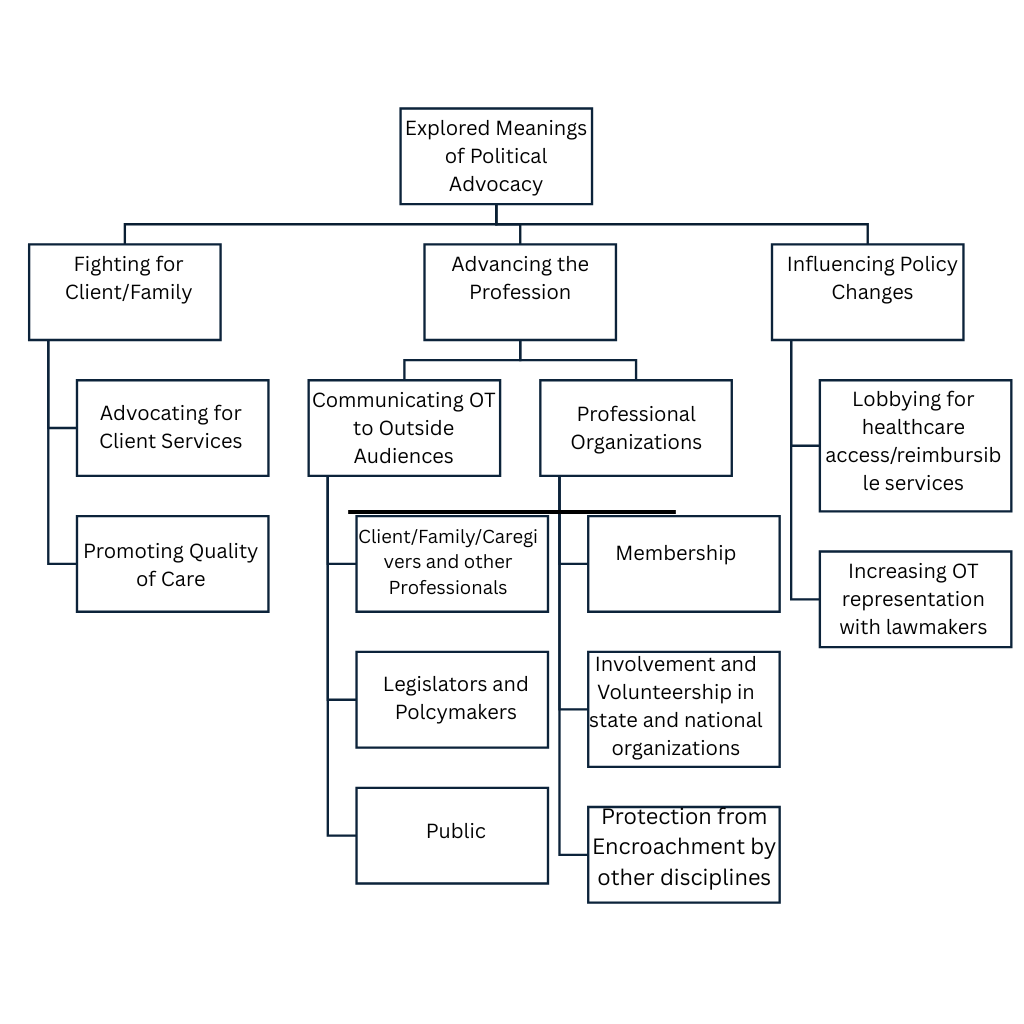

RESULTS: The data revealed three general themes: (1) fighting for client/family; (2) advancing the profession; and (3) influencing policy changes. Motivators and barriers to political advocacy were identified.

CONCLUSIONS: The current study underscored the need to incorporate political advocacy into OT education and stressed the importance of membership in professional associations. Apathy and lack of knowledge can be costly. Lack of participation in political advocacy ultimately places decision-making power in the hands of others whose understanding of OT practice and the healthcare system may be limited. Political advocacy participation offers an opportunity for OTPs to advance the profession and influence policies benefiting consumers of occupational therapy services.

Introduction

Congressional policies impact occupational therapy (OT) services, reimbursement, and consumer access to care. The American Occupational Therapy Association (AOTA) advocates for consumer access to care in legislation, including the Occupational Therapy Mental Health Parity Act, the Allied Health Diversity Workforce Act, and the Enabling More of the Physical and Occupational Workforce to Engage in Rehabilitation Act (EMPOWER Act).1 Despite the growing political nature of OT practice,2-5 many OTs struggle to frame their practices politically3,6 and lack awareness of policy’s impacts on OT services. Public policies influence OT practice7,8 and set boundaries for effective communication between individuals and institutions.7,9

OT and Political Advocacy

According to AOTA (2020)1 advocacy includes promoting occupational justice and is an intervention that includes disability rights advocacy such as “talking with legislators about improving transportation for older adults, developing services for people with disabilities to support living and working in communities of their choice, …and development of policies that address inequities in access to health care.”1,10

Political advocacy has been described as acts supporting change or issues on local, state, or federal levels enabling people to voice their opinions through emails, letters, calls, and social media posts to elected officials, or other methods.11 It can involve pleading the cause of others to promote change in social, economic, and educational norms.12,13 It includes support of policy or legislation and is a key component of political influence.1,14 Involvement can include membership in professional organizations and communication with legislators.15-17 Political advocacy promotes public policy development, healthcare policy reform,18,19 and social justice.20,21

AOTA’s Vision 2025 appeals to occupational therapy practitioners (OTPs) to work to change “policies, environments, and complex systems”22 by modifying structures to improve reimbursement for context-changing interventions.10

OT and the Humanities

While advocacy efforts underscore the importance of structural and policy-level change, the practice of occupational therapy also demands a deeply humanistic approach that centers on individual lived experiences. The health humanities offer a structural framework to examine the personal, social, and cultural dimensions of health and deepen the understanding of the broader impact of advocacy and client-centered care. Humanistic approaches help OTPs understand patients’ experiences by equipping them with the tools to empathize and understand the context of people’s lives.23

OTPs rely on client narratives of their lived experience, including their occupational histories and personal goals, which aligns with the humanistic approach of encouraging narrative thinking, where the client’s goals become part of client-centered care.24

Occupational therapists help clients find new or renewed interest in their everyday occupations while experiencing illness or disability, which is also congruent with humanistic approaches.

The Code of Ethics preamble states “AOTA members are committed to promoting inclusion, participation, safety, and well-being for all recipients of service in various stages of life, health, and illness and to empowering all beneficiaries of service to meet their occupational needs.”25 Political advocacy aligns with principles and core values in the Code of Ethics and sets forth Standards of Conduct the public can expect from those in the profession.25 Beneficence refers to taking actions to benefit others and Justice relates to fair, equitable, and appropriate treatment of persons.25 Both principles are crucial to advocacy as are the core values of altruism, equality, and justice.25

AOTA’s mission is advancing OT practice, education, and research through standard-setting and advocacy on behalf of its members, the profession, and the public.26 AOTA represents approximately 230,000 OTPs and students.26 There are 144,840 employed OTPs in the United States.27 Of these, only 65,000 are AOTA members, meaning that only one-fourth of the practitioners represented have membership in the professional association.

OT Practitioners and Advocacy

OT practitioners have opportunities to communicate the value of their profession to stakeholders at the daily-practice, professional, and systems levels.28 Hart (2020) postulated that advocacy promotes clients’ well-being and ensures that all who benefit have access to OT services.29

In daily practice, OTPs recognize the importance of advocacy as a professional role and work collaboratively with consumers to develop advocacy skills, including accessing information and systems to advocate for various supports.30 However, low advocacy levels among OTPs have been reported and may stem from inconsistent definitions of advocacy and a lack of guidance on advocating effectively.31 Practitioners and students should participate in political advocacy at the legislative and systems level to influence policies. Kirsh (2015) asserted that OTs can impact political and institutional agendas, reduce the social causes of occupational deprivation, and build the capacity to navigate challenges to advocacy.18

While political advocacy has been a research focus in other health professions, the meanings, perceptions, and participation among OT professionals have not been sufficiently explored in the literature. As OT practice is impacted more frequently by policies that affect consumer access to care and the way OTPs deliver services, it is imperative that OTPs advocate to ensure continued coverage of services and for professional viability and continuity. Therefore, this study analyzed the meanings, perceptions, and involvement in political advocacy by OTPs and students to determine gaps in practice, education, and research, and provide recommendations for change.

Political Advocacy in Occupational Therapy Literature

Although few studies explore the meaning and dynamics of political advocacy, the literature emphasizes the importance of OTPs and students’ participation in the profession’s political advocacy agenda.32-35 OTPs and students may utilize resources developed by professional organizations in their advocacy efforts. For example, AOTA publishes information reflecting the need for political advocacy for various health policy initiatives.11

Research has concentrated on advocacy relating to direct practice rather than political advocacy. Sachs and Linn (1997) examined situations where OTs identified client advocacy needs and factors affecting therapists’ behaviors when they protected, represented, or informed clients about their rights.36 OTs became advocates when mediation was needed to represent clients, and client advocacy was affected and shaped by the perceptions and experiences of their interdisciplinary team. These authors highlighted the necessity of a conceptual framework to help OTs understand how to advocate.36

Dhillon et al (2010) sought to understand the meaning of advocacy from OTPs’ perspectives.31 They found OTPs advocated because they experienced personal fulfillment, possessed power and influence, valued client-centeredness, assisted clients with engagement in occupation, and embraced human rights meeting basic needs and improving clients’ quality of life. They indicated that despite increasing recognition of the importance of advocacy, discussion of advocacy was often limited and disjointed.31 They recommended that OT education programs develop curricula to provide students with definitions and conceptual understandings of advocacy.

In a follow-up study, Dhillon et al (2016) found that the discussion of advocacy in literature and research often centered on skills supporting specific groups or marginalized populations in practice settings.37 They found OT participants advocated at the individual level on a case-by-case basis as part of client-centered practice, rather than advocating for and creating change at social policy and political action levels. They recommended the development of an advocacy framework to provide a common understanding of advocacy as multidimensional—individual, third-party, and task-specific.

While these studies illuminated advocacy specific to OT, none expounded on the meanings of and participation in political advocacy from practitioner and student perspectives. Therefore, our study explored the research questions:

- What does political advocacy mean from the perspective of practitioners and students?

- What factors facilitate or impede participation in political advocacy?

Methods

Study Design

This qualitative, descriptive study utilized in-depth interviews to explore participants’ perceptions, conceptualizations, and experiences regarding political advocacy. The University’s Institutional Review Board approved the study.

Participants and Procedures

Participants were recruited through convenience sampling at two regional OT professional meetings in California. Researchers distributed recruitment flyers at the event registrations. Six OTPs and seven OT students agreed to participate in the study. Of the 13 participants, one was male and 12 were female. Telephone interviews were performed one week after the events. Interviews averaged one hour per participant. Participants answered two open-ended questions about their participation in political advocacy. The questions were:

- What does being a political advocate mean to you?

- Have you participated in political advocacy activities? If so, how?

If they did not participate, participants were asked to explain why. Interviews were audiotaped and transcribed verbatim.

Data Analysis

Researchers collected data via a concept map of participants’ definitions of political advocacy and transcripts of telephone interviews. Concept mapping enables people to map ideas for any topic38 and was employed to understand perceptions of the term ‘political advocacy.’ Researchers created the concept map by listing all the definitions of advocacy that participants shared in the interviews. The definitions were placed on the concept map, and researchers reviewed the map for connections. The researchers used constant comparison methods to analyze and update the map by frequently returning to the data and updating it as more definitions and ideas about advocacy emerged.

Once the concept map was completed, researchers independently analyzed the data by performing first-cycle coding on the concept map and the telephone interview transcripts to determine the initial themes that emerged from the data. Second-cycle coding of the concept map and the telephone interview transcripts was performed collaboratively to determine final themes. The authors continuously returned to the data to refine their analysis. This constant comparison allowed investigators to re-examine the codes for meaning elements and consider how patterns and connections emerged to form themes.39 The trustworthiness of the analysis was established using reflexivity to reduce biases.40

At the time of the study, one author worked in hospital administration and held volunteer leadership positions in a state professional association involved in political advocacy activities. The other author worked in academia while holding volunteer leadership positions in state and national professional associations involved in political advocacy activities.

Results

Meanings of Political Advocacy

Narratives obtained from responses to the first question were analyzed using concept mapping to illustrate the meaning of political advocacy as viewed by respondents. Three general themes emerged:

- Fighting for client/family.

- Advancing the profession.

- Influencing policy changes.

(See Figure 1.)

Fighting for Client/Family

Nine out of 13 participants described political advocacy as protecting and fighting on behalf of clients and families regarding access to healthcare services while promoting quality of care. For example, Participant 8 defined political advocacy as:

“increasing access to services and programs and decreasing experiences of occupational deprivation while advancing research that improves the health and well-being of the population we serve.”

Participant 4 defined political advocacy as:

“supporting the quality, delivery, and access to care for our clients. It is support of legal and legislative structure, laws that affect client’s everyday lives.”

Participant 9 emphasized political advocacy as:

“really important because I want to have … the voice of my patients heard.”

Participant 6 viewed it as occurring:

“not just at the government level with lobbyist; it is also seen in patient care delivery.”

Advancing the Profession

The second theme centered on advancing the profession. Two broad categories emerged:

- Communicating OT to others.

- Involvement in professional organizations.

Most participants highlighted the need to communicate the role of OT to client/family/caregivers and other professionals and stakeholders. Participant 1 stated:

“Political advocacy is willingness to discuss what OT is to whoever wants to listen. It is an everyday grassroots approach. It means ‘sticking up’ for your profession.”

Participant 3 stated:

“Political advocacy can be every time we communicate with someone who is not an OT.” Several participants indicated a need for visibility and educating others on the profession’s distinct value.

Participant 6 described it as:

“…advocating in the workplace because many patients, families, caregivers do not know what we do.”

Similarly, Participant 4 stressed the importance of educating others, stating:

“Political advocacy is communicating what the profession is all about and how it services our community.”

Membership in state and national organizations to advance the profession was perceived as a part of political advocacy. Participant 2 described political advocacy as:

“volunteering or running for a board position and joining and becoming involved in your state or national organizations.”

Advancing the profession was also seen as a means of ensuring protection from encroachment by other disciplines, typified by Participant 5, who explained:

“Political advocacy is effort to solidify our boundaries as a profession since other professionals overlap with OT …having boundaries protects encroachment by other professions into OT’s domain.”

Influencing Policy Changes

The third theme centered on political advocacy as an opportunity to influence policy. Study participants discussed lobbying for access to reimbursable services and increasing representation with lawmakers to influence policies. Participant 10 explained:

“I think we really need to get our name out there. We need politicians and policymakers to know who we are first and foremost and have an understanding of what we do as OTs and our impact on so many people. I feel it would be less of a fight to keep our name in the circle so we can fight for insurance reimbursement.”

This was echoed by Participant 11:

“… political advocacy has to do with spreading awareness about our field and what our profession does and then lobbying for different clients and making sure we have rights to reimbursement….”

Participant 7 illustrated a need for practitioners and students to monitor and respond to policies that impact the profession:

“Political advocacy is knowing important legislation that pertains to our profession, getting informed about it, and keeping abreast of legislation affecting the profession.”

Motivators For and Barriers to Political Advocacy

The authors explored the range of activities considered political advocacy. This exploration revealed both motivators and barriers. Participants mentioned writing to legislators, contributing to political action committees, attending legislative events, becoming active in professional organizations, working alongside lobbyists regarding bills that impact OT, and participating in Hill Day activities. Analysis of data identified two motivators for and three barriers to political advocacy.

Motivation to Engage in Professional Political Advocacy

There was increased motivation to engage in political advocacy when legislation was deemed important and directly impacted work, clients, and practice. Participant 1 stated:

“As a practitioner, I may not be interested in all the bills. If I feel it is going to affect the population I work with, I can see myself be more involved with that particular bill.”

Similarly, Participant 5 stated:

“People may want to know legislation affecting their job in particular but not everyone might be interested in it affecting the profession as a whole. People are less apt to advocate if certain bills do not apply to them.”

Participant 10 stated:

“I did write to legislators about important issues and the need for OT research. When something comes up that is important concerning my practice, I react to it.”

Participants described their motivation to engage based on collaborating with lobbyists concerning scope-of-practice issues. Participant 3 stated:

“I am more concerned about who is going to protect our scope of practice and therefore I feel a need to go to our lobbyists to monitor these bills for the profession.”

Barriers to Professional Political Advocacy

Three themes emerged as barriers to political advocacy:

- Navigating time.

- Needing to become more politically astute.

- Feelings of indifference/apathy.

Needing More Time. Nine out of 13 participants reported problems devoting time to political advocacy activities, due to job demands and other professional and personal time priorities, including school and family obligations. Participant 1 stated:

“I am not active due to my busy schedule. I have 2 jobs and a part-time faculty job and a consulting business. I feel like I am spread thin, and it limits the amount of time I truly have to get involved.”

Participant 2 commented:

“I know I can be more active, but I just didn’t have the time.”

Participant 7 stated:

“I am not active in political advocacy as family obligations are taking up a lot of my time and energy.”

Participants also described focusing more on patient care than political advocacy activities. Participant 6 stated:

“My focus is on patient care and how to improve patient care directly. I don’t look at the big picture outside of patient care and how it directly affects us. Other things take more priority over this.”

Similarly, Participant 5 stated:

“I am more concerned about patient care and don’t really reflect on understanding the bills that affect our practice.”

Needing to Become More Astute. The second barrier was the need to increase political astuteness. Most participants lacked the confidence, skills, knowledge, education, or tools to access resources needed for political advocacy. Participant 2 stated:

“To seek it is in the back of my mind but not something I acted on. I am not active in political advocacy because I do not know where to go. The lack of knowledge of the issues is definitely a reason; I know it’s important, but I am not actively keeping an eye on our profession.”

Participant 4 also highlighted lack of knowledge, explaining:

“I am not too knowledgeable about the bills and therefore not sure how I can be of help. I have never talked to anyone in the political world.”

Statements about lack of confidence in political advocacy were related to individual or professional personality traits. Participant 13 mentioned:

“I am not active in political advocacy because I don’t feel comfortable being a ‘go-getter,’ out there telling people what I think.”

Participant 8 commented:

“I’ve heard that as OTs, we are some of the nicest people in the health profession and I don’t know if it comes into play as far as personalities that are attracted to the profession are not very assertive when it comes to standing up for certain injustices.”

Indifference/Apathy. The final barrier was feelings of indifference/apathy, reflected in statements that rejected the concept of political advocacy entirely. Indifference was found in statements describing an aversion to or disinterest in political advocacy, such as:

“It is not an interest of mine.” “I find it intimidating.” “I’ve never gone that far.” “I am not fond of politics.” “It is not my forte.”

Discussion

This qualitative study explored OT practitioners’ and students’ meanings of and participation in political advocacy. Data revealed varied definitions of political advocacy. The word “advocacy” is broad and ambiguous, with several definitions in the literature. Hayward and Li (2014) and Grace (2011) stated advocacy remains difficult to define and is an elusive concept.41,42 This elusiveness and ambiguity can be positive as each practitioner advocates based on their perceptions of the definition.

Findings revealed the need for an inclusive model, framing political advocacy at the systems level. This education can be disseminated via professional training and inclusion in professional documents or OT curricula. Kirsh (2015) stated advocacy is a professional imperative for OT and new competencies are needed in educational programs and professional development.18 This has been realized with the 2023 ACOTE (Accreditation Council in Occupational Therapy Education) standards, specifically, B.4.2, which states: “ Identify and analyze evolving service delivery models; changing federal, state, and local laws and regulations; and payment reform to advocate for occupational therapy.”43 This standard makes OT programs more likely to promote participation in political advocacy.

Two Critical Areas Emerged

Communicating OT to outside audiences and involvement in professional organizations emerged as critical areas of political advocacy.

Outside Communication and Involvement. To maintain and advance its professional status, OT must improve its recognition by the general public.44,45 Disseminating information to customers increases the likelihood of having a voice in political advocacy. Social media is a powerful mode for dissemination of information; Kirsh (2015) believes occupational therapists should become more astute in using social media for advocacy purposes.18

Professional Memberships. Participants felt membership and involvement in professional organizations increased their ability to have a voice in political advocacy. Advocacy has been regarded as a collective duty, assigned for professional associations to perform,46 due to individuals lacking the political clout to resolve systematic problems concerning patient care. Findings indicate that the profession must continually stress the importance of membership in professional associations. According to Matthews (2012), when greater numbers unite, the more powerful arguments can achieve advocacy outcomes.47

Lobbying

A third concept that emerged was influencing policy through lobbying for healthcare access and reimbursable services. Policy changes or the introduction of new legislation can be realized when interest groups advocate. Such actions lead to open dialogues and urge policymakers to examine the profession’s issues. Legislators may not have sufficient knowledge about OT to create laws for equitable access. Hence, OTPs and students need to have dialogues with elected officials.

A Need to Increase Incentives, Reduce Barriers

Findings also underscored the need to increase incentives (motivators) while reducing barriers.

Motivator: Identifying Legislative Impacts. Motivators included identifying specific legislation and its impact on participants’ work, clients, and practice. This is consistent with reports by Dhillon et al31 that therapists valued advocacy and learned this skill when required by job situations.

Motivator: Collaboration. Another motivator involved collaborative opportunities with lobbyists concerning scope of practice and encroachment.31 This statement is supported by Bonsall et al48: “If occupational therapists are not willing to advocate for the profession, other disciplines will encroach on aspects of practice that logically fall within the scope of occupational therapy practice.”48 Increasing knowledge of policy and legislative issues may be a fruitful strategy for engaging in political advocacy.

The Time Barrier. Navigating time was a significant barrier. Time constraints have been identified in the literature as a barrier to participating in professional advocacy by health educators.49-54 However, while some activities require extensive time, others such as emailing an elected official may involve fewer than 5 minutes. Hancher-Rauch, et al (2019) suggest setting time aside, “even just a minute or two a day to read updates from the field relevant to the issues about which you are passionate.”15 Therefore, practitioners must reallocate time to engage in advocacy activities.15,51 Professional OT organizations may find ways to encourage and incentivize participation by making political advocacy easy, simple, and accessible. AOTA makes it simple for members to contact their legislators by providing ways to send electronic communications via their website.

Lack of Resources. Another barrier was participants lacking the confidence, skills, knowledge, and education to access resources needed for political advocacy. The perception of not having the knowledge or skills to engage in advocacy has been documented in the literature.15,51,55 While advocacy requires problem-solving, communication, influence, and collaboration,56 the results of this study suggest participation in political advocacy activities harnesses skills, improves knowledge, and builds confidence. Practitioners and students can begin by advocating for a specific piece of legislation and focusing on learning more about its potential impact on clients and practice. This increases political astuteness or “awareness and understanding of legislative and policy processes, and political skills.”57 As practitioners become more politically astute, they can access resources necessary for political advocacy.

Reluctance. Advocacy is a professional and ethical responsibility.15,58 The current study exposed feelings of indifference and aversion to political advocacy. While being an advocate means involvement in the political sphere, many players in healthcare are reluctant to get involved in politics.59 Occupational therapy practitioners should be motivated to participate in the policy-making processes. Hajizadeh et al (2014) found that nurses can influence through their experiences with policies, laws, and regulations that govern the healthcare system.60 OTPs should aspire to have this same influence. Disinterest in political advocacy initiatives could prove problematic for clients and healthcare providers. Health professionals, including OTPs, are on the frontlines witnessing the everyday needs of individuals, groups, and populations. They have an important role in representing the needs of consumers and communities through health advocacy initiatives. Reliance on a select few for political advocacy related to OT may allow other individuals and groups to prevail when they support positions counter to the profession.

Limitations

Study limitations included a small sample size and limited geographical representation as responses collected represented only one state. Future research could explore similar research questions in diverse geographic locations. The development and evaluation of formal educational training to increase knowledge, skills, and confidence by practitioners and students in political advocacy may also be explored. Other limitations that could have impacted the study include researcher confirmation bias, involving researchers searching for, interpreting, and recalling information that confirms pre-existing beliefs or hypotheses.61 Interpretation bias, researchers misinterpreting participants’ responses due to subjective judgment, leading to erroneous conclusions, could also impact the study.61 Researchers mitigated these issues by reflecting on personal values, beliefs, and biases. Member checking was also performed to validate the accuracy of the interviews.

Conclusion

With constant changes occurring in healthcare, there has never been a better time for OTPs and students to engage in political advocacy. To protect consumers and remain relevant as a profession, OTPs need to understand political advocacy. The profession’s educational programs and professional associations should encourage, educate, and incentivize practitioners and students to advocate and reduce barriers.

The current study underscored the need to incorporate political advocacy into OT education and stressed the importance of membership in professional associations. Apathy and lack of knowledge can be costly. Lack of participation in political advocacy ultimately places decision-making power in the hands of others whose understanding of OT practice and the healthcare system may be limited. Political advocacy participation offers an opportunity for OTPs to advance the profession and influence policies benefiting consumers of occupational therapy services.

Acknowledgment: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose and no funding to report.

References

- American Occupational Therapy Association. Advocacy & policy. Am J Occup Ther. 2020;73(3). doi:https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2019.733002

- Townsend E, Galipeault JP, Gliddon K, Little S, Moore C, Klein BS. Reflections on power and justice in enabling occupation. Can J Occup Ther. 2003;70(2):74-87. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/000841740307000203

- Aldrich RM, Rudman DL. Occupational therapists as street-level bureaucrats: leveraging the political nature of everyday practice. Can J Occup Ther. 2019;87(2). doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0008417419892712

- Baillard AL, Aldrich RM. Occupational Justice in everyday occupational therapy practice. In: Dikaios Sakellariou NP, ed. Occupational Therapies Without Borders: Integrating Justice with Practice. Second ed. Elsevier; 2017:chap 9.

- Njelesani J, Teachman G, Durocher E, Hamdani Y, Phelan SK. Thinking critically about client-centred practice and occupational possibilities across the life-span. Scand J Occup Ther. 2014;22(4):252-259. doi:https://doi.org/10.3109/11038128.2015.1049550

- Galvin D, Wilding C, Whiteford G. Utopian visions/dystopian realities: exploring practice and taking action to enable human rights and occupational justice in a hospital context. Aus Occup Ther J. 2011;58(5):378-385. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1630.2011.00967.x

- Osman A, Webber C, Oliel S, Couture-Lavoie K, Lencucha R, Shikako-Thomas K. Engagement of occupational therapy organizations with public policy: a qualitative analysis. Can J Occup Ther. 2020;87(5):354–363. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0008417420961689

- Lencucha R, Shikako-Thomas K. Examining the intersection of policy and occupational therapy: a scoping review. Can J Occup Ther. 2019;86(3):185-195. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0008417419833183

- Torjman S. What is Policy? Caledon Institute of Social Policy; 2005.

- Harrison EA, Sheth AJ, Kish J, et al. Disability studies and occupational therapy: renewing the call for change. Am J Occup Ther. 2021;75(4):7504170010. doi:https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2021.754002

- Political Advocacy: Definition. https://www.quorum.us/public-affairs-dictionary/political-advocacy-definition/

- Benner P, Sutphen M, Leonard V, Day L. Educating Nurses: A Call for Radical Transformation. Jossey-Bass; 2009. Institute of Medicine. The Future of Nursing: Leading Change, Advancing Health. Vol 2023. National Academy Press; 2011.

- Staebler S, Campbell J, Cornelius P, et al. Policy and political advocacy: comparison study of nursing faculty to determine current practices, perceptions, and barriers to teaching health policy. J Prof Nurse. 2017;33(5):350–355. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.profnurs.2017.04.001

- Hancher-Rauch HL, Gebru Y, Carson AT. Health advocacy for busy professionals: effective advocacy with little time. Health Prom Pract. 2019;20(4):489-493. doi:10.1177/1524839919830927

- Byrd ME, Costello J, Gremel K, Schwager J, Blanchette L, Malloy TE. Political astuteness of baccalaureate nursing students following an active learning experience in health policy. Public Health Nurs. 2012;29(5):433-443. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1446.2012.01032.x

- Clark MJ. Community nursing: health care for today and tomorrow. Reston Publishing; 1984.

- Kirsh BH. Transforming values into action: advocacy as a professional imperative. Can J Occup Ther. 2015;82(4):212–223. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0008417415601395

- Reutter LI, Duncan SM. Preparing nurses to promote health-enhancing public policies. Policy Pol Nurs Pract. 2002;3(4):294-305. doi:10.1177/152715402237441

- Gupta J. Mapping the evolving ideas of occupational justice: a critical analysis. 2016;36(4):179-194. doi:10.1177/1539449216672171

- Reutter L, Kushner KE. Health equity through action on the social determinants of health: taking up the challenge in nursing. Nurs Inq. 2010;17(3):269–280. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1800.2010.00500.x

- American Occupational Therapy Association. AOTA board expands Vision 2025. Am J Occup Ther. 2019;73:7303420010. doi:https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2019.733002

- Murray R, McKay E, Thompson S, Donald M. Practising reflection: a medical humanities approach to occupational therapist education. Med Teacher. 2000;22(3):276-281. doi:doi:10.1080/01421590050006250

- Charon R. Narrative Medicine: A model for empathy, reflection, profession, and trust. JAMA. 2001;286(15):1897-1902. doi:doi:10.1001/jama.286.15.1897

- Occupational Therapy Code of Ethics. Am J Occup Ther. 2020;74(Supplement_3):7413410005p1–7413410005p13. doi:https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2020.74S3006 American Occupational Therapy Association. Mission and vision. Available at: https://www.aota.org/Advocacy-Policy.aspx. Accessed [date].

- S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Occupational Therapists. Available at: https://www.bls.gov/ooh/healthcare/occupational-therapists.htm. Accessed [date].

- Hart E, Lamb AJ. A Mindful Path to Leadership Series Module 4: A Mindful Path to Advocacy. A Mindful Path to Leadership. AOTA Continuing Education; 2018.

- Hart E. Becoming an Advocate. 6th ed. Occupational Therapy Manager. AOTA Press; 2020.

- Hammel J, Charlton J, Jones RA, Kramer JM, Wilson T. Disability rights and advocacy: partnering with disability communities to support full participation in society. In: Barbara A. Boyt Schell GG, Marjorie Scaffa, Ellen Cohn eds. Willard & Spackman’s Occupational Therapy. 12th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2014:1031-1050:chap 70.

- Dhillon SK, Wilkins S, Law MC, Stewart DA, Tremblay M. Advocacy in occupational therapy: exploring clinicians’ reasons and experiences of advocacy. Can J Occup Ther. 2010;77(4):241–248. doi:https://doi.org/10.2182/cjot.2010.77.4.6

- Stover AD. Client-centered advocacy: every occupational therapy practitioner’s responsibility to understand medical necessity. Am J Occup Ther. 2016;70(75):7005090010p1–7005090010p6. doi:https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2016.705003

- Fisher G, Friesema J. Implications of the Affordable Care Act for occupational therapy practitioners providing services to Medicare recipients. Am J Occup Ther. 2013;67(5):502–506. doi:https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2013.675002

- Hildenbrand WC, Lamb AJ. Occupational therapy in prevention and wellness: retaining relevance in a new health care world. Am J Occup Ther. 2013;67(3):266-271. doi:10.5014/ajot.2013.673001

- Stoffel VC. Opportunities for occupational therapy behavioral health: a call to action. Am J Occup Ther. 2013;67(2):140-145. doi:https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2013.672001

- Sachs D, Linn R. Client advocacy in action: professional and environmental factors affecting israeli occupational therapists’ behaviour. Can J Occup Ther. 1997;64(3):207-215. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/000841749706400316

- Dhillon S, Wilkins S, Stewart D, Law M. Understanding advocacy in action: a qualitative study. Br J Occup Ther. 2016;79(6):345-352. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0308022615583305

- Trochim WM, McLinden D. Introduction to a special issue on concept mapping. Eval Prog Plan. 2017;60:166–175. doi:10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2016.10.006

- Sechelski AN, Onwuegbuzie AJ. A Call for enhancing saturation at the qualitative data analysis stage via the use of multiple qualitative data analysis approaches. Qual Rep. 2019;24(4):795-821. 6. doi:https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2019.3554

- Ahmed SK. The pillars of trustworthiness in qualitative research. J Med Surg Pub Health. 2024;2. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.glmedi.2024.100051

- Hayward LM, Li L. Promoting and assessing cultural competence, professional identity, and advocacy in doctor of physical therapy (dpt) degree students within a community of practice. J Phys Ther Educ. 2014;28(1):23-36.

- Grace PJ. Professional advocacy: widening the scope of accountability. Nurs Phil. 2001;2:151-162. doi:https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1466-769X.2001.00048.x

- ACOTE Accreditation Standards. AOTA. Available at: https://acoteonline.org/accreditation-explained/standards/. Accessed [date].

- Carrier A, Freeman A, Desrosiers J, Levasseur M. Institutional context: what elements shape how community occupational therapists think about their clients’ care? Health Soc Care Community. 2020;28:1209–1219. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12954

- Cooper JE. Reflections on the professionalization of occupational therapy: time to put down the looking glass. Can J Occup Ther. 2012;79(4):199-209. doi:https://doi.org/10.2182/cjot.2012.79.4.2

- Welchman J, Griener GG. Patient advocacy and professional associations: individual and collective responsibilities. Nurs Ethics. 2005;12(3):296–304. doi:https://doi.org/10.1191/0969733005ne791oa

- Matthews JH. Role of professional organizations in advocating for the nursing profession. OJIN. 2012;17(1):Manuscript 3. doi:https://doi.org/10.3912/OJIN.Vol17No01Man03

- Bonsall A, Wolf RL, Saffer A. Experiential education in advocacy for occupational therapy students: didactic approaches and learning outcomes. J Occup Ther Educ. 2023;7(2). doi:https://doi.org/10.26681/jote.2023.070207

- Gosselin-Acomb TK, Schneider S, Clough RW, Veenstra BA. Nursing advocacy in North Carolina. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2007;34(5):1070-1074. doi:10.1188/07.ONF.1070-1074

- Cramer ME. Factors influencing organized political participation in nursing. Policy, Polit Nurs Pract. 2002;3(2):97-107. doi:10.1177/152715440200300203

- Galer-Unti RA, Tappe MK, Lachenmay S. Advocacy 101: getting started in health education advocacy. Health Prom Prac. 2004;5(3):280–288. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1524839903257697

- Holtrop J, Price JH, Boardley D. Public policy involvement by health educators. Am J Health Behav. 2000;24(2):132-142.

- Clark P, Holden C, Russell M, Downs H. The imposter phenomenon in mental health professionals: relationships among compassion fatigue, burnout, and compassion satisfaction. Contemp Fam Ther J. 2022;44(2):185–197. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10591-021-09580-y

- Winter MK, Lockhart JS. From motivation to action: understanding nurses’ political involvement. Nurs Health Care Perspect. 1997;18(5):244–250.

- Hossain MS, Conteh E, Ismail S, Francois P, Tran D, MacIntosh T. Perceptions of advocacy in high school students: a pilot study. Cureus. 2023;15(6):e40581. doi:10.7759/cureus.40581

- Tomajan K. Advocating for nurses and nursing. 2012;17(1):Manuscript 4. doi:https://doi.org/10.3912/OJIN.Vol17No01Man04

- Primomo J. Changes in political astuteness after a health systems and policy course. Nurse Educ. 2007;32(6):260-264. doi:10.1097/01.NNE.0000299480.54506.44

- Tappe MK, Galer-Unti RA. Health educators’ role in promoting health literacy and advocacy for the 21st century. J School Health. 2001;71(10):477-482. doi:10.1111/j.1746-1561.2001.tb07284.x.

- Siedlecki CR. Political Influence: Why and How Healthcare Leaders Must Get Involved. medical Group Management Association. 2024. https://www.mgma.com/MGMA/media/files/fellowship%20papers/Political-Influence-Why-and-How-Healthcare-Leaders-Must-Get-Involved_2.pdf?ext=.pdf

- Hajizadeh A, Zamanzadeh V, Kakemam E, Bahreini R, Khodayari-Zarnaq R. Factors influencing nurses’ participation in the health policy-making process: A systematic review. BMC Nursing. 2014;20(1) doi:10.1186/s12912-021-00648-6

- Lemire M. Navigating Bias in Qualitative Research: Identifying and Mitigating Its Impact. 2/11/2025, 2025. https://www.qrca.org/blogpost/1488356/506750/Navigating-Bias-in-Qualitative-Research-Identifying-and-Mitigating-Its-Impact

About the Author(s)

Luis Arabit

Luis Arabit, OTD, MS, OTR/L, BCN, BCPR, C/NDT, PAM, FAOTA is an Associate Professor at San Jose State University, College of Health and Human Sciences, Occupational Therapy Department. He is an accomplished and experienced occupational therapist with a demonstrated history of working in the hospital and healthcare as well as higher education industry. He received his Bachelor of Science degree in Occupational Therapy from the University of the Philippines, Manila, his Master’s in Science degree in Rehabilitation Sciences from Texas Tech University, and his Doctoral degree in Occupational Therapy from the University of Saint Augustine, FL. He currently teaches Professional Development, Leadership, Administration and Management, and OT with Middle- Aged and Older Adults in both the Masters and Doctoral OT programs. He has served in various volunteer leadership positions in state, regional, and national associations. His research interests include advocacy, caregiving, faculty development, student engagement, OT and AI, and orthopedic shoulder rehabilitation.

Pamela Lewis-Kipkulei

Pamela Lewis-Kipkulei, PhD, OTD, OTR/L is an Associate Professor at the University of Tennessee Health Science Center. She has been an occupational therapist for over 30 years and has been in academia for the past decade. She received a Bachelor of Science in Occupational Therapy from Washington University in St. Louis, a Master of Science in Education from Harding University, a Clinical Doctorate from Chatham University, and a Doctor of Philosophy from Walden University. She currently teaches the Evidence-Based Practice series and serves as the Capstone Coordinator for UTHSC’s OTD program. Her research interests include advocacy, student engagement, and participation in the learning process.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.