Exploration of the Use of Balint Groups in Physical Therapy Education

Table of Contents

Introduction

History of Balint Groups

Balint groups were developed by psychoanalysts Michael and Enid Balint in the 1950s for physicians to explore the relational and emotional aspects of providing patient care.1 In Balint groups, a small group of clinicians meets regularly to discuss cases from their practices, with a focus on the humanistic aspects involved in providing care and practicing perspective-taking of varied lived experiences. Balint groups allow for structured peer discussion on the therapeutic patient relationship and emotional reflection to develop empathy, self-awareness (including biases or assumptions), insight into the psychosocial aspects of patients, and understanding of one’s own emotional reactions that may impact patient care.2,3,4

Importance of Empathy

Loss of empathy has been reported in medical students as they move through the clinical phases of their training.1,5 When investigating empathy, many definitions were uncovered; however, the choice was made to adopt Hojat et al’s definition and that of the Jefferson Scale of Empathy. Empathy in patient care is defined as a predominantly cognitive (rather than an affective or emotional) attribute that involves an understanding (rather than feeling) of the pain and suffering of the patient, combined with a capacity to communicate this understanding, and an intention to help.6 The four key terms in this definition (understanding patient’s pain, cognitive rather than solely emotional attribute, capacity to communicate, and intention to help) underscore their significance in the construct of empathy in patient care, and make a distinction between empathy and sympathy (which is defined as a predominantly emotional reaction). This distinction is important because empathy and sympathy have different consequences in clinical outcomes. Primarily, empathy is seeing situations from another’s point of view without losing your own perspective.7 Adopting this definition of empathy allows the construct of empathy to be broken down and investigated for its various characteristics. Scaffolding and guidance can then be provided to students and novice clinicians allowing an in-depth examination of empathy and its effects on the formation of clinical relationships.

It has been proven that health professionals with high levels of empathy operate more efficiently as to the fulfillment of their role in eliciting therapeutic change. The empathetic professional comprehends the needs of the healthcare users, as the latter feel safe to express the thoughts and problems that concern them.8 Empathy is crucial in patient care because it allows healthcare providers to truly understand a patient’s emotions, experiences, and perspective, which leads to stronger connection, improved communication, increased trust, and ultimately, better treatment outcomes and patient satisfaction.6

Balint groups have been implemented in medical education, most often in primary care, to address this issue by exploring ways of heightening students’ awareness of the emotional, non-biomedical aspects of the lived experience of illness and the dynamics of the clinician-patient relationship via the Balint group method.1,3,9 Several studies have identified that participation in Balint groups increased medical students’ empathy.1,2,5,10 There is also evidence to suggest that Balint-type groups reduce participants’ sense of isolation and may have further clinical and psychological benefits.1 Other documented benefits for those who participate in Balint groups include: feeling less alone in clinical work; realizing that others had similar experiences and frustrations to themselves; and cultivating the ability to disclose uncertainty and emotional impact without it being used against them.1,5

Use of Balint Groups

Various systematic reviews investigating the use of Balint groups in medical education have identified both qualitative and quantitative findings demonstrated in the literature. Qualitative findings suggest that Balint groups assist in personal and professional development, helping residents to understand the impact of their own personality characteristics on patient care.9 Quantitative studies did not always imply that Balint groups increased patient-centeredness; however, Balint groups did increase the students’ knowledge and abilities of the clinician-patient relationship with the potential to improve communication skills, and improved their ability to manage the psychological aspect of medicine.1,9,11

Themes identified in a longitudinal study where residents participated in twice-monthly Balint groups for 24 months included:

- Having the ability to identify blind spots within the clinician-patient relationship.

- Being the physician the patient needs.

- Reducing burnout by providing an outlet and creating a bond with others who have similar experiences.

- Improving reflection skills.

- Identifying the importance of empathy (Player et al3).

Utilizing Balint groups has also been shown to reduce burnout among primary healthcare doctors.12,13

Nicole Piemonte14 states that “developing vulnerability will lead to a more sustainable, more fulfilling healthcare experience for providers.” Balint targets this vulnerability in the process of hearing a case and “living” the experiences of those involved by imagining the perspectives of the humans involved. This further exploration of the lived human experience is a direct connection to the humanities. Luna et al15 describe methods used in Doctor of Physical Therapy (DPT) programs offering humanities exposure to students that include encounters with real patients, caregivers, and family members, allowing experiential learning. Additionally, Luna et al15 introduce “health humanities”—a more inclusive term that welcomes different perspectives and engagements. These experiences are thought to enhance clinician observation skills, interprofessional readiness, non-verbal communication, professionalism, and cultural humility.

Barrett et al16 describe Balint groups as a form of storytelling and share that “storytelling and the patient history are very much at the heart of medicine.” They cite Charon’s work from 201218 describing clinical medicine as a “narrative undertaking fortified by learnable skills in understanding stories has helped doctors and teachers to face otherwise vexing problems in medical practice and education in the areas of professionalism, medical interviewing, reflective practice, patient-centered care, and self-awareness.”

In response to Barrett et al’s work, medical students Antrum and Burchill17 shared that narrative is fundamental to understanding the human experience, describing that in medicine, clinicians are regularly put in situations that challenge emotions and conceptions of self—often requiring difficult decisions—and that this creates conflict between procedural medicine and the interactions with patients. They note some of Charon’s earlier work, which states “as clinicians, it is fundamental to develop narrative competence.”18

Balint Groups in Healthcare Professions

There has been little research on the use of Balint groups in healthcare professions other than for physicians. In addition, there is limited work that investigates the use of Balint groups and their effects on the development of the cognitive-affective domain in health professions students. In the last several years, there has been a call for DPT education to more explicitly address the cultivation of students’ affective domain or ‘habits of the heart.’19

Promoting the development of affective skills in DPT and other health professions students is important for improving empathy, enhancing cultural humility, improving provider emotional well-being, and reducing provider burnout. By using the humanities in shaping these afore-mentioned characteristics, both students’ and clinicians’ affective domain skills are further developed. Students benefit from opportunities to explore the vulnerability and potential suffering of the lived experience of illness or injury to better attend to the humanistic needs of patients.

The Model for Excellence and Innovation and the American Council of Academic Physical Therapy’s excellence framework in academic physical therapy has identified the importance of concepts grounded in the affective domain—including shared beliefs and values, partnerships and collaborations, leadership, and innovation, as well as social responsibility and inclusion. The explicit use of the affective domain in physical therapy education equips the future of the profession with the knowledge, skills, and affect to meet stakeholder needs and endure the demands of clinical practice.20

The purpose of this article is to demonstrate how Balint groups may be a potential tool to provide such an opportunity to address students’ affective domain development, how Balint can be incorporated into DPT curricula, and their potential benefits for DPT students.

Description of the Implementation of Balint Into a DPT Curriculum

One DPT program chose to pilot the incorporation of Balint groups into their first full-time clinical experience course (CE1) to address course objectives relevant to the development of students’ affective domain skills. The relevant course objectives addressed with the Balint group pilot focused on areas of professional behaviors including:

- Empathy and compassion

- Productive working relationships

- Practicing in a manner consistent with professional standards and ethical guidelines.

- Communication

- Cultural humility

- Use of reflection for ongoing professional development.

Additionally, based on the evidence of Balint group participation contributing to improved emotional well-being, resiliency, and decreased isolation, we wanted to explore if our students would also perceive any of these benefits.

The CE1 course is the first of three supervised full-time clinical education experiences occurring in the 4th semester of an 8-semester curriculum. This 10-week clinical placement follows the first full year of coursework, which includes two part-time integrated clinical experiences (ICE)—one in the inpatient setting and the other in an outpatient orthopedic setting. Students’ CE1 can occur in any physical therapy setting, although a majority of students are placed in outpatient orthopedic settings based on the didactic course content they have had thus far in the curriculum and on clinical site resource availability. During CE1, students are expected to become proficient and consistent in performing examinations/evaluations, interventions, and clinical reasoning in non-complex cases with supervision from their clinical instructor.

Participation Required

Balint group participation was established as a requirement of the CE1 course. The Balint sessions were an hour in length and met in the evenings during weeks 3, 6, and 9 of the 10-week clinical experience. Groups of seven to eight students and two facilitators met for the three sessions utilizing an in-person, virtual, or hybrid format.

- The first session was held virtually for all students.

- The second session was held in-person for all students completing their clinical experience locally and remained virtual for students completing CE1 at a distance. The second session also included scheduled time for students to socialize either in person or in the virtual environment for those at a distance.

- In the final session, the students had a choice to come in person or attend virtually, resulting in hybrid formats.

The Balint group facilitators were DPT program faculty or associated faculty who received training in the Balint method from two credentialed Balint leaders. Students were introduced to the Balint group process during an orientation class for the CE1 course prior to the start of their clinical experience and had access to resources including descriptions of Balint groups.

The Balint Group Experience

During the groups, facilitators opened the discussion with reminders regarding confidentiality, maintaining mutual respect, and speaking without judgment. Further, they highlighted the Balint goal of being curious and exploring thoughts, emotions, and perspectives regarding the humanistic aspect of cases versus trying to solve the challenges presented or focusing on the technical or clinical aspects of the case.

A Narrative Case and Discussion. Students were then asked for a volunteer to share a narrative case from memory that may have “stuck” with them due to any emotional or challenging interpersonal encounters. Once the student (presenter) presented their “case,” facilitators offered the opportunity for participants to ask clarifying questions before the presenter “pushed back,” removing themselves from the discussion and listening to the group members discuss the case.

The facilitators then invited the group members to conjecture about the imagined experiences of their peer student clinician, the patient, the clinical instructor, and anyone else involved in the case, including the role of emotions in these encounters and potential dynamics in the clinician-patient, student-patient, student-clinician, or student-caregiver relationship. As needed, facilitators ensured the focus was on imagining, curiosity, empathy, and feelings versus providing advice or finding solutions to the challenges.

Finally, the facilitators then invited the volunteer presenter back into the discussion to optionally share any comments, reactions to what they heard, or share new insights as a result of the discussion. Most groups discussed two different cases in each session; however, some more involved cases utilized the full hour.

Reflection. During the CE1 course, students also participated in asynchronous discussion posts with their peers, responding to prompts and peer reflections during 8 of the 10 weeks of the course. The discussion posts were not graded but were audited for completion as a requirement of the course.

The final prompt asked students to reflect on their participation in Balint groups:

“How did your participation in Balint groups influence your clinician-patient relationships, communication, patient care, or ability to navigate the emotions of challenging patient interactions during CE1?”

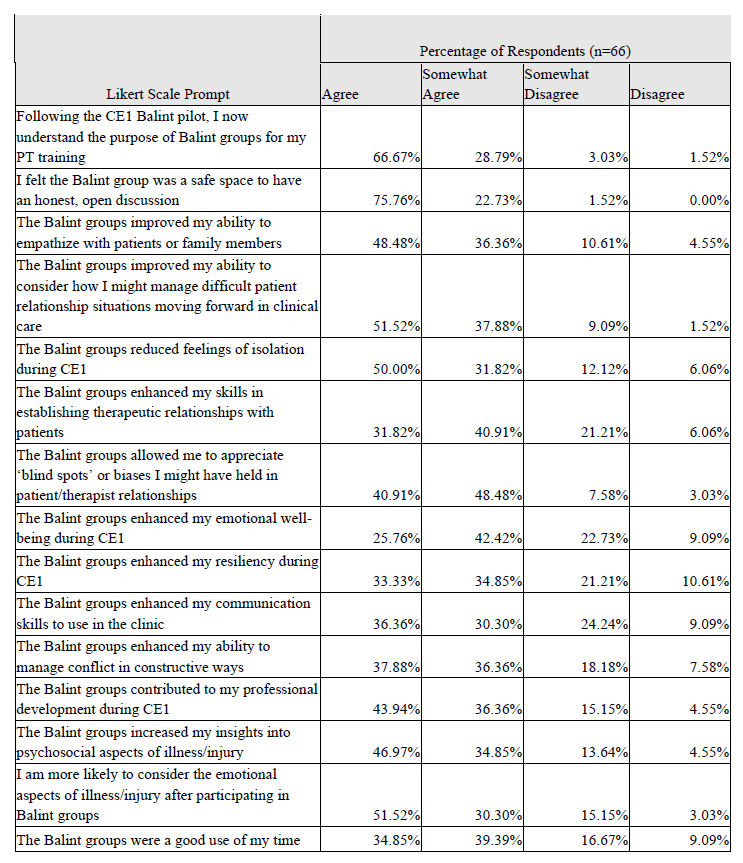

These discussion responses were then de-identified, and a qualitative analysis was completed to establish themes. Students were also required to complete a program evaluation survey to inform future applications of Balint groups within the DPT curriculum. The survey, using a Likert scale, asked for student perspectives regarding the effectiveness of Balint groups in developing affective skills pertaining to course objectives and the perceived benefits of the groups that had been previously identified in the literature. The Likert results were analyzed with descriptive statistics.

Pilot Balint Outcomes

Student experience with the Balint group process was assessed with: 1) the program evaluation student survey Likert scale questions; and 2) qualitative analysis of the reflective discussion board posts. The Likert survey questions and response data are shared in Table 1.

The survey results demonstrate strong support for students valuing the Balint group experience with improvements in understanding the psychosocial aspects of illness, improved communication skills, and improved therapeutic relationship development. Additionally, students felt Balint groups contributed to improvements in their own emotional well-being and resilience while experiencing reduced feelings of isolation during this first clinical experience.

While the results were largely positive, some students disagreed with the majority of their peers with aspects of this survey. An example of these mixed opinions was the “therapeutic relationship establishment enhancement.” For this category, 48 students (72.73%) responded with agree or somewhat agree, while 18 students (27.27%) responded with somewhat disagree or disagree. When analyzing the item “Balint groups were a good use of my time” 49 students (74.24%) agreed or somewhat agreed while 17 (25.76%) somewhat disagreed or disagreed.

The student reflective discussion board posts responding to the prompt “How did your participation in Balint groups influence your clinician-patient relationships, communication, patient care, or ability to navigate the emotions of challenging patient interactions during CE1?” were analyzed.

These posts were analyzed to identify themes utilizing a framework established by Braun and Clarke.21 Three of the researchers independently coded the data and identified themes. Meetings of the three researchers were utilized to synthesize the codes and themes leading to team agreement. Three themes were determined through this triangulation process. Balint group participation: 1) created valued community; 2) improved clinical communication and relationships; and 3) enhanced emotional awareness.

Theme 1: Created Valued Community

Students shared that the Balint group process provided a safe learning environment where they were able to learn from others’ experiences and perspectives and gained expertise in reflective practice. They appreciated the support, validation, and camaraderie received from their peers. Further, simply having an opportunity to share time together (whether in person or virtually) during the clinical experience when they are otherwise in various locations independent of one another appeared beneficial to community building as the students reported appreciation for the opportunity to connect with their peers and that the groups helped to decrease the feelings of isolation they experienced during CE1.

One student shared:

“While we are all experiencing CE1 together, all of our experiences have been different, so it helps to learn from others while having support whether it be theoretical or emotional.”

Another student reflected:

“The group allowed us to validate our thoughts, feelings and current development and helped us to realize that we’re not alone in the journey.”

Another student found:

“There was comfort in the shared struggles and the group helped normalize the struggles and allowed space to process the emotions.”

Theme 2: Improved Clinical Communication and Relationships

Students reported that participation in these groups helped them to view patient care more holistically, and more deeply understanding the importance of the others involved in the process, including care providers, clinical instructors, spouses, children, parents, and friends. Students reported feeling an increased level of empathy through this work. They felt more equipped to have difficult conversations with patients, caregivers, and the care team after these Balint group discussions.

One student shared:

“The group helped me to see situations from different perspectives that I had not thought of before.”

Another student shared:

“The groups encouraged me to communicate more deeply with patients and display empathy and compassion to foster an environment they feel comfortable in…by creating a safe space for patients we can navigate these difficult situations easier.”

Additionally, one student reflected about their awareness of their clinical instructor:

“The Balint process helped me view the perspective of my CI more thoroughly. This helped me to understand where they were coming from better.”

Theme 3: Enhanced Emotional Awareness

Value was found for students in the space the groups provided to allow for emotional processing. They learned the importance of considering the alternative perspectives present in not only the patients, but other members of the healthcare team, their clinical instructor, and families. They felt that the humanistic complexities of patient care were highlighted by the group work.

One student shared this reflection:

“I feel like we have a lot of difficult emotions to face in the day-to-day with the valid frustrations of our patients. During these difficult times, the primary focus is to reassure the patient, but we cannot forget about ourselves, too.”

The impacts of student participation are clear from the examples shared above, both in the survey data and more descriptively in the reflective discussion post themes. These data suggest that the affective domain described as vital to healthcare delivery by Berg-Carramusa20 was targeted effectively in this project.

Limitations

The discussion posts analyzed for themes were mandatory assignments during the students’ clinical education experience as was attendance to the Balint groups. Although there is no letter grade assigned to clinical experiences (they are pass/fail), discussion board posts may be subject to social desirability bias given students want to portray a positive clinical experience. Students may be reluctant to show vulnerability in their posts or reluctant to post an opposing viewpoint. Students may feel the need to compose reflections that they perceive is the “correct” or “expected” answer rather than their true perceptions.

Discussion and Conclusions

The qualitative data and themes identified in this project are similar to those found in previous studies assessing Balint groups’ influence on medical residents,3,9 including: improving communication (Theme 2); feeling validated and knowing peers have similar experiences and frustrations as themselves (Theme 1); and developing the ability to disclose the emotional impact of patient care (Theme 3). Although similar themes were identified in previous studies, the relationships and challenges that medical residents experience may be different than those experienced by DPT students.

This project begins to investigate the influence of Balint groups in health professional students other than physicians. To date, the influences of Balint groups on non-physician providers is limited; however, Dahlgren et al22 studied Balint groups with physiotherapists with the emphasis on practice awareness and communication. Yousefzadeh et al23 studied the effectiveness of Balint groups among a limited number of psychiatric nurses and found that the groups were not effective in improving the well-being and communication skills of the participants; hence, the need for further investigation.

Player et al3 identified that Balint groups reduced the burnout in residents by allowing them to bond with peers who had similar experiences. The knowledge that you are “not alone” was reassuring and residents identified that there was a supportive network to access. Although not explicitly stated, reduction of burnout may be identified as a theme among these DPT students, given they identified creating a valued community and enhancing emotional awareness as themes. One could postulate that these two themes would contribute to reducing burnout.

Given the emphasis on incorporating explicit learning activities to address affective domain development in DPT education, this pilot implementation of Balint groups demonstrates potential benefits consistent with Balint in medicine and the broader scope of narrative medicine. Balint groups allow exposure and opportunity for sharing perspectives and emotions related to the human elements of patient care with multiple benefits raised.

Students reported that the Balint groups improved their ability to communicate, manage conflict and difficult patient relationship situations, empathize, and develop therapeutic relationships with patients. Further, the groups allowed students to appreciate biases they may have held in clinician-patient relationships and increased their awareness of the psychosocial and emotional aspects of illness/injury. Although it can be hypothesized that by enhancing emotional awareness and improving clinical communication and relationships would lead to improved empathy, further study to investigate this hypothesis is needed.

While some students did have a less positive experience, the majority of students did find considerable value in the Balint process. One consideration is that students were mandated to participate in these Balint groups following their scheduled days during their clinical experiences, and this may have contributed to some of the less positive perspectives. The literature regarding the use of Balint groups in medical education shares a mix of required and voluntary participation.1,2 This concept will need to be considered for future Balint group implementation as there is an argument for allowing voluntary opt-in to increase autonomy and allow further affective domain development in those that are ready to participate in contrast to those who may not be interested.

Balint groups can provide DPT students the opportunity to recognize and understand the emotions awakened in clinical encounters, for both student and patient. While encouraging a heightened sensitivity to a patient’s emotional state and life context, such groups can also encourage students, through practice, to better appreciate their own emotional responses to illness and to communicate more empathically with their patients, particularly through attentive, non-judgmental listening.

Overall, this work displays a novel inclusion of Balint groups in DPT clinical education with narrative storytelling and describes the students’ perceived positive impact on their affective domain skills and emotional well-being during their first full-time clinical education experience. There appears to be value in continuing to utilize the Balint groups to supplement traditional coursework; however, further studies are warranted.

References

- Salter E, Hayes A, Hart R, et al. Balint groups with junior doctors: a systematic review. Psychoanal Psychother. 2020;34(3):184-204.

- Adams K, O’Reilly M, Room J, James K. Effect of Balint training on resident professionalism. AM J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195(5):1431-1437.

- Player M, Freedy J, Diaz V, et al. The role of Balint group training in the professional and personal development of family medicine residents. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2018;53(1-2):24-38. doi:10.1177/0091217417745289

- Gajree N. Can Balint groups fill a gap in medical curricula? Clin Teach. 2021;18(2):158-162.

- O’Neill S, Foster K, Gilbert-Obrart A. The Balint group experience for medical students: a pilot project. Psychoanal Psychother. 2016;30(1):96-108.

- Hojat M, DeSantis J, Shannon S, et al. The Jefferson Scale of Empathy: a nationwide study of measurement properties, underlying components, latent variable structure, and national norms in medical students. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2018;23(5):899-920.

- Santos M, Grosseman S, Morelli, T, et al. Empathy differences by gender and specialty preference in medical students: a study in Brazil. Int J Med Educ. 2016;21(7):149-153. doi:10.5116/ijme.572f.115f.

- Moudatsou M, Stavropoulou A, Philalithis A, Koukouli S. The role of empathy in health and social care professionals. Healthcare (Basel). 2020;8(1):26-35.

- Yazdankhahfard M, Haghani F, Omid A. The Balint group and its application in medical education: a systematic review. J Educ Health Promot. 2019;8:124. doi:10.4103/jehp.jehp_423_18

- McManus S, Killeen D, Hartnett Y, Fitzgerald G, Murphy K. Establishing and evaluating a Balint group for fourth-year medical students at an Irish University. Ir J Psychol Med. 2020;37(2):99-105.

- Barr-Sela G, Lulav-Grinwald D, Mitnik I. “Balint Group” meetings for oncology residents as a tool to improve therapeutic communication skills and reduce burnout level. J Cancer Educ. 2012;27(4):786-789.

- Stojanovic-Tasic M, Latas M, Milosevic N, et al. Is Balint training associated with the reduced burnout among primary health care doctors? Libyan J Med. 2018;13(1):1440123. doi:10.1080/19932820.2018.1440123

- Kannai R, Biderman A. Methods for burnout prevention and their implementation in the course for family medicine residents in Ben-Gurion University of the Negev. Harefuah. 2019;158(10):664-668.

- Piemonte N. Returning back to oneself: cultivating vulnerability in the health professions. J Humanit Rehabil. 2019;(3):1-7. Available at: https://www.jhrehab.org/2019/04/15/returning-back-to-oneself-cultivating-vulnerability-in-the-health-professions/. Accessed [August 23, 2024].

- Luna S, Brown N, Dodds C. Humanities instruction in physical therapy education to cultivate empathy, recognize implicit bias, and enhance communication: a case series. J Humanit Rehabil. 2022;(3):1-11. Available at: https://www.jhrehab.org/2022/04/25/humanities-instruction-in-physical-therapy-education-to-cultivate-empathy-recognize-implicit-bias-and-enhance-communication-a-case-series/. Accessed [August 23, 2024].

- Barrett E, Dickson M, Hayes-Brady C, Wheelock H. Storytelling and poetry in the time of coronavirus. Ir J Psychol Med. 2020;37(4):278-282.

- Antrum E, Burchill E. Storytelling and poetry in the time of coronavirus: medical students’ perspective. Ir J Psychol Med. 2020;39(4):440-442.

- Charon R. The patient-physician relationship. Narrative medicine: a model for empathy, reflection, profession, and trust. JAMA. 2001;286(15):1897-1902.

- Nordstrom T, Jensen G, Altenburger P, et al. Crises as the crucible for change in physical therapist education. Phys Ther. 2022;102(7):pzac055. doi:10.1093/ptj/pzac055

- Berg-Carramusa C, Mucha M, Somers K, Piemonte N. The time is now: leveraging the affective domain in pt education and clinical practice. J Phys Ther Educ. 2023;37(2):102-107. doi:10.1097/JTE.0000000000000271.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77-101.

- Dahlgren M, Almquist A, Krook J. Physiotherapists in Balint group training. Physiother Res Int. 2000;5(2):85-95. doi:10.1002/pri.188.

- Yousefzadeh N, Dehkordi M, Vahedi M, Astaneh A, Bateni F. The effectiveness of Balint group work on the quality of work life, resilience, and nurse-patient communication skills among psychiatric nurses: a randomized controlled trial. Front Psychol. 2024;15(1). doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1212200.

About the Author

Jane Baldwin, DPT, NCS

Dr. Baldwin is an Assistant Professor and Associate Chair in the Department of Physical Therapy at the MGH Institute of Health Professions (IHP). She served as the inaugural coordinator for the Marjorie Ionta Physical Therapy Center for Clinical Education and Health Promotion, a center where students, under the direct supervision of faculty, provide evidence-based pro bono services to both adults and children. She received her BS in Physical Therapy from Northeastern University and her Doctor of Physical Therapy from Simmons University. Dr. Baldwin has had numerous clinical and administration positions in a variety of settings working with both adults and children with neurological conditions. Research interests include interprofessional education, student outcomes, outcomes for those with chronic neurological conditions, global health/service learning, and telehealth. She is a Board Certified Clinical Specialist in Neurological Physical Therapy and a Fellow of the National Academies of Practice.

Monica Arrigo, DPT

Monica Arrigo is an Assistant Professor in the Doctor of Physical Therapy Program in the School of Health and Rehabilitation Sciences at the MGH Institute of Health Professions in Boston, MA. Her faculty appointment focuses on the program’s clinical education curriculum, and she also teaches in the Institute’s Interprofessional curriculum. In addition to her academic responsibilities, Dr. Arrigo maintains a clinical practice in the long-term acute care setting.

Dr. Arrigo’s scholarly agenda centers on the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, with a focus on innovative methodologies in clinical education to support student professional growth and belonging. She is particularly interested in developing affective domain skills in Doctor of Physical Therapy students. Recently, she has been examining the benefits of incorporating Balint groups within clinical education courses and has presented her findings nationally.

Christopher Clock, DPT, OCS

After graduating from Boston University, Christopher started his clinical career at a community hospital working in the inpatient, sub-acute rehabilitation, and outpatient wings of the hospital. He developed a passion for outpatient orthopedics and has spent the majority of his 25 year clinical career working in an outpatient physical therapy setting. His career has included time in San Diego, Seattle, and Boston. He is a board certified orthopedic clinical specialist.

His academic pursuits began as he worked as a lab instructor at the University of Washington in their physical therapy program. Since returning to the northeast, he has been involved at MGH Institute of Health Professions as a teaching assistant, adjunct clinical faculty, instructor and since the fall of 2022, an Assistant Professor.

Anne McCarthy Jacobson, DPT, MS

Dr. McCarthy Jacobson has been on the faculty at the MGH Institute of Health Professions since 1997 where she is an Assistant Professor in the Graduate Programs in Physical Therapy. She teaches in the entry-level Doctor of Physical Therapy program, with a primary focus in clinical management and rehabilitation of neuromuscular disorders in children and adults, in addition to orthotics, limb loss and prosthetics, and diagnostic screening.

She maintains a clinical practice at Spaulding Rehabilitation Hospital in Boston, MA, where she is a clinical expert physical therapist on the Inpatient Service; primarily treating children and adults with neurologic and complex medical disorders. Additionally, she provides consults for physical therapists working with patients with vestibular, balance, and movement disorders.

She received the MGH Institute of Health Professions’ Nancy T. Watts Award for Excellence in Teaching and is the past recipient of the Institute’s Marjorie K. Ionta Clinical Excellence Award in Physical Therapy, as well as a three-time recipient of the Spaulding Rehab Hospital Clinical Excellence Award. She is an active member of the American Physical Therapy Association (APTA) and the Academy of Neurology Physical Therapy of the APTA, currently serving as Co-Chair of the Knowledge Translation Movement Analysis of Tasks Task Force.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.