Table of Contents

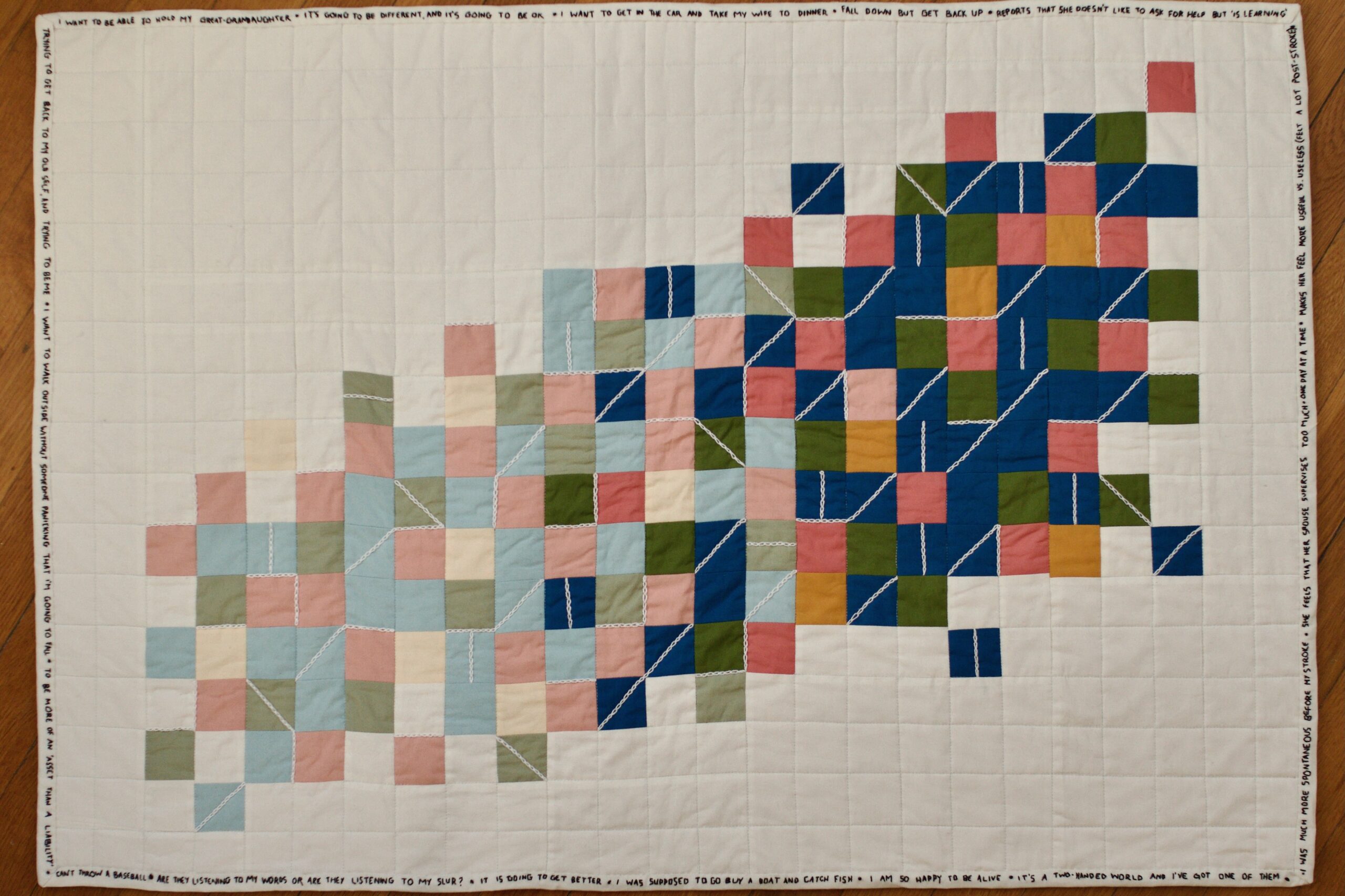

“I was much more spontaneous before my stroke. – I want to get in the car and take my wife to dinner. – I want to climb into a bathtub and take a bath. – Interacting with people makes [me] feel useful vs. useless.”

These phrases were selected from a collection of qualitative interviews our team conducted with 30 chronic stroke survivors. The study sought to understand how psychosocial factors affect success in a telerehabilitation occupational therapy program. This was done through a series of assessments, including a semi-structured interview using the American Occupational Therapy Association Occupational Profile (AOTA 2020).1

During this interview, stroke survivors were asked about their personal histories, including self-described barriers to and supports for engaging in meaningful occupations. As I repeatedly read and tried to analyze the resulting stories through the lens of an occupational therapist and scientist, I couldn’t move past the emotion present in the pages of text.

As I poured through spreadsheets and piles of interviews, I was struck by the dichotomy of life post-stroke: profound grief and loss of personal identity and bodily autonomy contrasted with the emergence of new physical and emotional strength and resilience, recovery of function and capability, and rediscovery of self—all supported by personal relationships along the way. I asked myself: How could I reduce the stories of these unique individuals and their complex emotions into black-and-white data points on a graph?

Adding the Creative Perspective

I am historically a “numbers person,” finding comfort in finite data, letting the statistics drive fact vs. fiction. As I sat at my computer searching for meaning in the stories shared by these stroke survivors, I found myself wrapped in their voices, the weight of their words echoing in my head. I realized our qualitative dataset lacked the definitive boundaries to which I was accustomed. Instead, the data was rich with raw emotion and ambiguity.

Growing up, I always had a flair for creative pursuits, particularly of the textile flavor. I was raised by creative women, learning from my mother, stepmother, grandmother, and great-aunt the joys of transforming fabric and thread from two to three dimensions. With various colors and patterns, each piece elicits sensations emotionally and physically: the softness and warmth of a favorite sweater, the weight and smell of Dad’s favorite blanket.

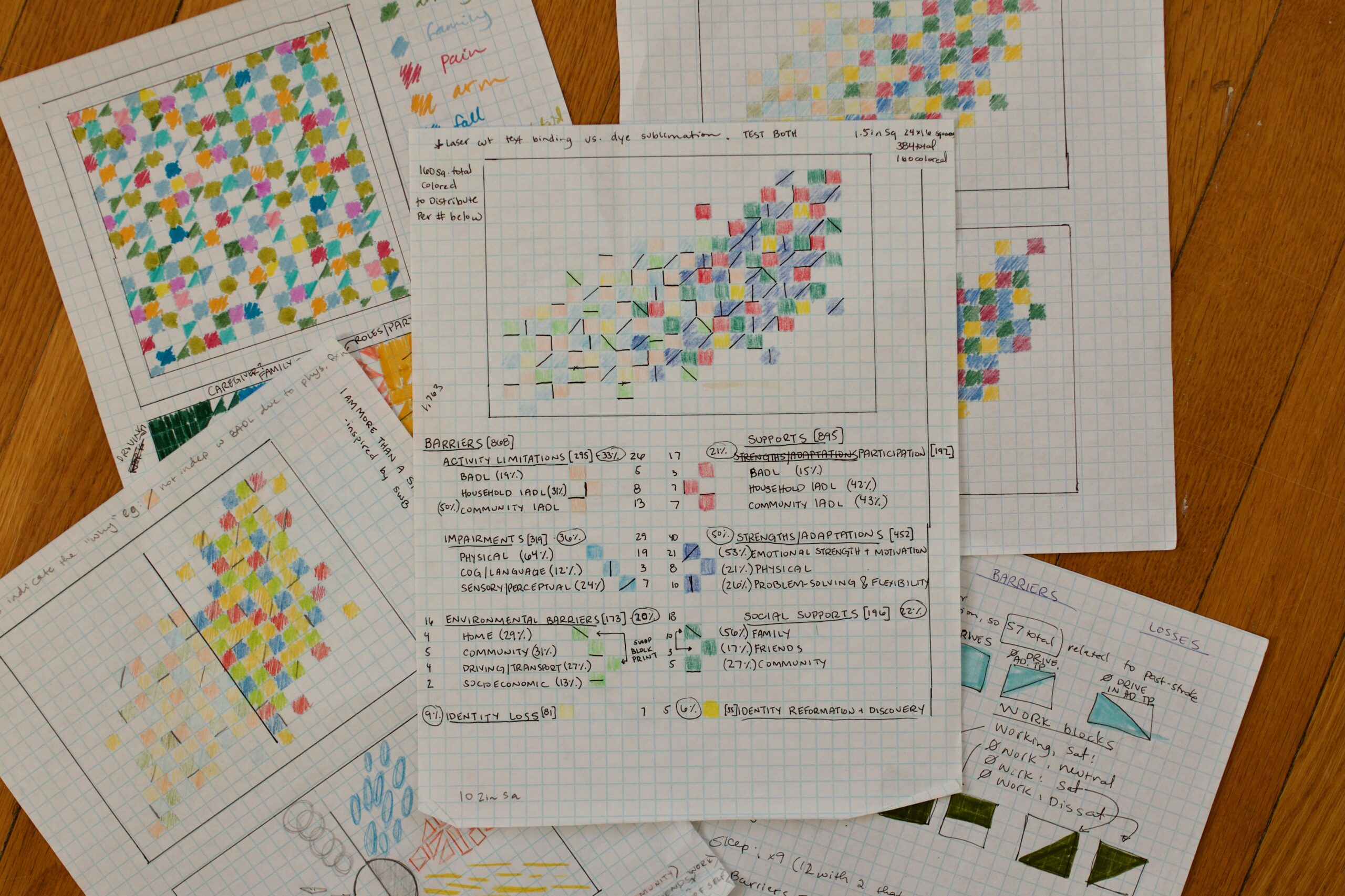

In reflecting upon my next directions, I came across one of my favorite books, Dear Data, by Giorgia Lupi, an Italian designer who specializes in complex data visualization. She writes in her manifesto titled Data Humanism that we must begin to “connect numbers to what they really stand for: knowledge, behaviors, people.”2 All my attempts to tell the data’s story through tallying and graphs fell flat, so I turned to the medium I know best: quilting.

Perceiving the Colors of Emotion

The black-and-white text and tallied categories started to come to life in various shapes and colors. As I sat cutting, piecing, and quilting, I thought about each person on their journey: desaturated hues for losses and environmental barriers, saturated hues for strengths both internal and external to these stroke survivors. In placing the colors in sequence, reaching upward from the depths of grief to the heights of personal growth and resilience, I thought about where each individual lay on this trajectory.

The mixing of color along the continuum also shows that this progress is not always linear. Some barriers and challenges may persist, though fading into the background as personal strength builds and recovery progresses. Each square brings softness to these survivors’ words that ink and paper cannot convey. White lines separate the subcategories of data and represent the individuals’ unchosen link with each chain stitch.

Where Data Falls Short

As clinicians and scientists, our work is shaped by the desire to reduce suffering and improve lives. So often, these efforts are lost in translation, obscuring the humanity of the individual lived experience with numerical data and simple categorization. Grief and recovery are deeply personal, often uncomfortable, and their end ambiguous. Where science demands objectivity, creative exploration of data through artistic practices allows us to embrace the value of subjectivity and emotion, diving deeper into the complexities of what it means to be human.

It has been an honor to work through these stroke survivors’ stories with my hands, each person sitting in my lap sharing their hopes and dreams for the future and bravely transitioning from a life that once was.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to my team who supported this project in many ways: Michelle Woodbury for leaving space for quiet reflection and pushing my boundaries, Steph Garner for many hours of data analysis, and Jul Laura and Patty Finetto for your unfailing friendship and editing eyes. I’m honored to share my days with you.

References

- AOTA Occupational Profile Template. (2017). The American Journal of Occupational Therapy : official publication of the American Occupational Therapy Association, 71(Supplement_2); 7112420030:p1. Available at: https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2017.716S12. Accessed November 18, 2024.

- Lupi, G. Data humanism: the revolutionary future of data visualization. Print. 2017. Available at: https://www.printmag.com/article/data-humanism-future-of-data-visualization/. Accessed November 18, 2024.

About the Author(s)

Kelly Rishe, MSOT, OTR/L

Kelly is a research Occupational Therapist with the Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC) Stroke Recovery Research Center and the Massachusetts General Hospital Laboratory for Translational Neurorecovery. She also serves as an adjunct instructor in the Doctor of Occupational Therapy programs at MUSC and Baylor University. Kelly holds a B.S. in Biology from Mississippi State University and an M.S. in Occupational Therapy from the Medical University of South Carolina. Kelly has worked with stroke survivors and other neurologic populations for ten years, and her patients’ voices and experiences have shaped her passion for improving quality of life and the lived-experience of disability.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.