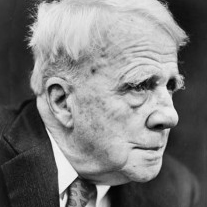

Poet in Profile – Robert Frost (1874-1963)

By Marilyn McEntyre, Ph.D., UCB-UCSF Joint Medical Program

Robert Frost was one of the most well-known and widely read American poets, writing realistic depictions of rural life in early twentieth century New England. He received four Pulitzer Prizes for Poetry, the Congressional Gold Medal, and was named Poet Laureate of Vermont.

Robert Frost was one of the most well-known and widely read American poets, writing realistic depictions of rural life in early twentieth century New England. He received four Pulitzer Prizes for Poetry, the Congressional Gold Medal, and was named Poet Laureate of Vermont.

Image credit: Walter Albertin, World Telegram staff photographer – Library of Congress. New York World-Telegram & Sun Collection.

The Road Not Taken – Robert Frost, 1916

Two roads diverged in a yellow wood,

And sorry I could not travel both

And be one traveler, long I stood

And looked down one as far as I could

To where it bent in the undergrowth;

Then took the other, as just as fair,

And having perhaps the better claim,

Because it was grassy and wanted wear;

Though as for that the passing there

Had worn them really about the same,

And both that morning equally lay

In leaves no step had trodden black.

Oh, I kept the first for another day!

Yet knowing how way leads on to way,

I doubted if I should ever come back.

I shall be telling this with a sigh

Somewhere ages and ages hence:

Two roads diverged in a wood, and I—

I took the one less traveled by,

And that has made all the difference.

Frost R. “The Road Not Taken.” In: Edward Connery Lathem, ed. The Poetry of Robert Frost. New York NY: Henry Holt and Company;1969.

Two Leafy Roads

Robert Frost’s 1916 poem “The Road Not Taken” remains, 100 years after its publication, one of the two or three most widely read poems in the U.S. It is taught in classrooms, quoted in ads, alluded to in songs, and pillaged for book titles. Poet Randall Jarrell, Frost’s junior by 40 years, referred to Frost’s poetry as “magically good.”1(p.85) Thousands of readers have memorized “The Road Not Taken,” some, it is edifying to note, even without the aid of an English teacher’s insistence.

The poem moves many readers to reflect on and aspire to the independence it takes to choose “the road less traveled.” “I took the one less traveled by,” the speaker claims at the end, “and that has made all the difference.” That reading of the poem has real value, especially in the ways it has inspired young people making big decisions for the first time, setting out on careers, resisting the centripetal force of social pressures to consider the less likely alternatives and harken, at least for a moment, to their own “drumbeat.”

A less widely recognized reading, which David Orr has explored extensively in his 2015 book on the poem and its “misreadings,” suggests that the poem is not at all about personal independence, but, ironically, about the ways we construct our stories after the fact, assigning significance to suit the shape of a good story.2 He notes, as others have, the fact that both roads “that morning equally lay / in leaves no step had trodden black.” It is morning. Autumn leaves have fallen and (this being New England) carpeted the paths so thickly it is impossible to tell which is “less traveled.” They lie equal. One might as well take the left as the right. To foreground that line is to recognize the role of chance (or fate or providence or intuition of which we can give little account) in what turn out to be our most consequential decisions. What unfolds from those moments may well be a series of choices that have “made all the difference.” But the choice of the road itself is less an act of courageous independence than a decision more like that of Melville’s Ishmael who did not set out on a heroic journey, but simply, “having little or no money in my purse, and nothing particular to interest me on shore” thought he would “sail about a little and see the watery part of the world.” Thus two great American journeys begin in a strangely offhand, open-ended way.

The poem may well be a critique of a too-simple idea of heroic nonconformity and a warning not to take too seriously the stories we tell ourselves about ourselves, including those in history books. Yet, as some generous critics have conceded, the “darker” reading doesn’t invalidate the more commonly understood message of the poem. What we shall be telling “ages and ages hence” about our own choices, even if our stories are embellished by hindsight, will be stories that serve new purposes. We negotiate meaning as we go along, weaving happenstance with intention. Even the most earnest autobiography relies on fictive devices; used appropriately, they are instruments of truthtelling. Life is neither novel nor poem; to call it a journey is to choose one metaphor among others. But poets know there is method and meaning in our metaphors. In those choices, too, “way leads on to way” enticing us, as Emily Dickinson put it, to “dwell in possibility.”3

It is good to consider more than one reading of a poem. And then to choose, at least for the time being, which has “the better claim.”

Robert Frost’s own life was riddled with tragic loss. Behind his four Pulitzer Prizes, Congressional Gold Medal, his term as poet laureate and many other public honors lay a family history that included cancer, early death, suicide and mental illness, and poverty. His farming ventures were largely unsuccessful; he spent most of his life writing and teaching, following a road we have good reason to be glad he traveled. In “The Gift Outright,” the poem he recited at JFK’s inauguration4, he left lines that have served, similarly to those in “The Road Not Taken” to inspire rich and fruitful reflection on our personal and collective choices: “Something we were withholding made us weak / Until we found out that it was ourselves…”

References

- Jarrell, Randall. “Fifty Years of American Poetry.” No Other Book: Selected Essays. New York: HarperCollins, 1999.

- Orr, D. The Road Not Taken: Finding America in the Poem Everyone Loves and Almost Everyone Gets Wrong. 1st New York, NY: Penguin Press; 2015.

- Dickinson, E. “I Dwell in Possibility” In: RW Franklin ed. The Poems of Emily Dickinson. Harvard University Press; 1999.

- Frost, R. “The Gift Outright”: Poem recited at John F. Kennedy’s Inauguration. John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum. http://www.jfklibrary.org/Research/Research-Aids/Ready-Reference/JFK-Fast-Facts/Frost-Gift-Outright.aspx. Accessed May 13, 2016.

Member since 2019 | JM14274

Member since 2019 | JM14274

NO COMMENT