Scarred for Life: Using Art to Bring Humanity to Trauma Recovery

By Ted Meyer

About the Artist

Ted Meyer is a nationally recognized artist, curator and patient advocate who helps patients, students and medical professionals see the positive in the worst life can offer. Ted’s 18-year project “Scarred for Life: Mono-prints of Human Scars” chronicles the trauma and courage of people who have lived through accidents and health crises. Ted’s paintings have been shown around the world, from Europe, to Asia, and throughout the United States. With subject matter ranging from introspective, to down-right humorous, his narrative always looks at human interactions.

Ted has been featured on NPR and in the New York Times, Washington Post, Chicago Tribune, and USA Today. His work has been displayed internationally in museums, hospitals, and galleries. As the former Artist in Residence at UCLA Geffen School of Medicine, Ted curated exhibitions of artwork by patients whose subject matter coincides with medical school curriculum. Ted has curated shows by artists challenged by MS, cancer, germ phobias, back pain, and other diseases. In addition, he is a Visiting Scholar at the National Museum of Health and Medicine, and was recently invited to take part in the Aspen Seminars at the Aspen Institute.

The Ted Meyer Story

People often ask me: “How did you land up being the Artist in Residence at a medical school?” Is it really so unbelievable that the guy who wrote and illustrated a children’s book about cats titled “The Butt Hello” could have anything to add to a discussion at a big deal medical school?

When I look at all the different aspects of my life, the outcome seems quite logical. Multiple stays in the hospital, the lady with the art cart, drawing in my hospital bed, the ease I feel in a hospital, all were a part of a clear path. I see these pieces as a path, directing me from the disappointment my parents felt when I announced I wanted to be an artist, to serving as artist in residence at UCLA’s Geffen School of Medicine for the past 5 years, and now onto USC Keck School of Medicine to develop a larger program starting in the fall of 2016.

I was born with Gaucher Disease, a rare genetic illness. I lived through multiple childhood hospital stays and spent years painting pain, loneliness, and fatigue. I got really good at it. Pain as a subject suited me. I might not have sold a lot of my contorted skeletons, or angry figure paintings. But, I got good press. My paintings were getting shown. I showed work from coast to coast. Gaucher had provided me a never-ending source of artistic motivation.

Other than my failing health, everything was going well. That is, until stupid western medicine butted in with a treatment that offered to end my pains and extend my life expectancy to that of a “normal” person. In a single biotech miracle, some faceless pharma company stripped me of my artistic direction. Life-saving drugs left me doing paintings that were no longer about suffering or angst, but love and happiness. It was enough to drive a healthy guy into depression.

I spent a year or two in artistic purgatory with no real vision. Until one night, at an art gallery, I met a lovely wheel chair user. She was sporting a long scar on her back that she showed off proudly in a backless dress. Her name was Joy and she was a joy; a real human homonym. We discussed art and our changing life situations. How at that point we were moving in seemingly different directions. I was getting more active, and she, less mobile. The interesting thing was that she was actually expanding her life. She was cast on a TV show and started working with a dance company to add rolling to their vocabulary of standard dance moves. She told me that although I was now healthy, I should still be doing work about health and mobility because it was all still part of me.

I mulled that over for a bit, and because she was really beautiful, I thought she might be right. I called her that night and asked if I could make a contact print of her scar as a way to tell her story. So I showed up at her house a few hours later with ink, roller and paper and made the first print in my Scarred for Life series. A long blue imprint that clearly showed incision, stitching and the unnatural bend in Joy’s back where it had been broken.

At the first opportunity I showed Joy’s scar along with those of two other people. The reaction was unexpected. Gallery goers, normally more interested in cheese squares and wine, lined up to discuss the print as well as tell me of their scars. I heard stories of accidents, operations and violence. People unbuttoned shirts and pulled down pants, they practically undressed in the gallery while giving me details of their strength and survival, all the while pointing to their scars. It was like nothing I had experienced. I came to realize that there was a BIG need for scar victims, even those considered done with their recovery, to tell their stories to complete their healing. They needed recognition of their struggles, and of survival.

For the next 12 years I collected scars, and I collected stories, and made prints. I heard tales of operations and recovery, of organs removed and replaced, arms and legs lost to nature and autos. During that time I learned that the people who landed up in my studio were not defined by their traumas or missing body parts, they were instead an amalgam of pre- and post- scar narratives; both aspects linking together over the scar to create a new meaning of the experience and of their lives.

I listened to my scar models’ histories, I heard about their medical care and about doctors who were fantastic with a blade, yet less fantastic with their bedside manner. I thought of my own medical care and the doctor, a wiz at sports medicine and joint replacement, who brought a group of med students into my room to show them “his scars” (a result of a my bi-lateral hip replacement). He was excited to show them how neatly “his scars” had turned out because he did such a skillful job. I know it was just semantics but it was on my new hip, and it was my skin, so I sort of thought of it as my scar, however he clearly took ownership of my body.

With my mixture of personal stories, first-hand accounts, and a love of art, I thought, what can I do with all this to change the doctor/patient discussion? Could I get doctors to see their patients as I did? As people with developing stories accented by treatment or trauma that kept unfolding years after treatment might have finished.

I thought if I could get to the students early, when they were still learning the art of medicine, I might be able to affect a change in how they looked at their patients. I came up with an idea to bring art by patient-artists into the medical school and tie their work to what was being studied that quarter. For example, if the students were looking at the respiratory system I might find an artist with Asthma. An artist who was shot in the brain would cover neurological. Shows on back pain, cancer, migraines, dementia and adult disabilities followed. I’d give them gallery shows and arrange a Q & A with the students and direct the artists to explain how their medical conditions motivated them to make art; how experiencing their particular illness, rather than limiting their lives, actually expanded their artistic horizons.

With a great deal of patience and perseverance I was finally able to get in touch with the Dean of Education at the UCLA Geffen School of Medicine. I told her my idea of a patient-artist gallery as a learning tool for the school and within 20 minutes I had an appointment for the next day to come in and pitch my program.

Five years later, after 19 shows featuring 23 artists and garnering fantastic press, what have I accomplished? As an artist and curator I have given a lot of artists a showplace for work that normally would be hidden. It is generally accepted that art should be about something… until it is. Then people want to see a sunset. Work about cancer, bipolar disorder and electro shock therapy, no matter now beautiful, generally does not get shown in the art world. I’ve created a venue for art with a strong personal medical narrative.

Then there are the medical students. Did I reach my goal of getting them to think differently about their future patients? Yes, I hope so. I hope that the effects of such learning in the short term is of broadening a student’s horizons, to allow them to investigate outside the boundaries of what has been traditionally defined as the world of medicine. The longer term effects are upon the creation of a sensibility that allows for the unknown to exist, for humility to develop towards a patient’s experience.

Dominic Quagliozzi, an artist with Cystic Fibrosis creates artwork about his repeated hospital stays actually using his hospital time to make new work about his ordeal. His work expresses the boring routine of repeated hospitalizations. During his talk you could have heard a pin drop as he explained, and showed in his paintings, what it was like to live life on a waiting list for new lungs. Susan Trackman, an MS patient talked about losing control of life while showing the intricate patterns she makes from all her spent medical vials. “The only control I have over my medical life is what patterns I make with all the junk it generates,” she said.

Art has kept me sane during my life with Gaucher and it has given others insight into what I go through. It has worked for me and I know it works for others. I know that compelling art can teach new doctors a lot about the conditions they will be treating

My long-term goal is to expand my program to other medical schools. There is no reason these shows can’t travel from school to school with matching educational materials.

It is an opportune time to be doing this work, as the field of Health Humanities, Narrative Medicine, and the number of visual and performing arts programs in major medical schools continue to grow. The climate of medical practice and the healthcare system is undergoing a radical change, with major governing bodies like the ACGME and AAMC amongst others charging the field of medical education with the radical proposition of training doctors who are reflective and humanistic as well as technologically savvy.

Scarred for Life Project

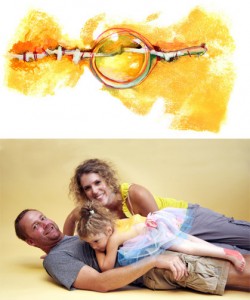

For over 18 years Meyer has been creating a graphic yet beautiful depiction of people’s suddenly altered bodies and the resulting scars in an ever-enlarging collection of artworks entitled, “Scarred for Life.” “Scarred for Life” continues to grow and now consists of almost 100 artistically enhanced monoprints taken directly from the scarred skin of his subjects. Each image – accompanied by a photographic portrait taken by Ted and a written story by his subject – tells a unique and intriguing story of medical crisis, resilience and healing.

The project’s title embodies a duality of ideas that are explored in depth: first, that medically related scars or physical disfigurements often have a profound lifelong impact on a patient’s self-identity, and secondly, that those scars have the potential to serve as powerful symbols of regeneration and life, and learning tools as well. Exploring facets of self-adornment, contemporary trends in body modification and the ways in which art has been used to redefine aesthetic norms, Scarred for Life presents ways in which medical patients can grow to view their scars as beautiful symbols of personal resilience.

Meyer has recently joined up with Dr. Simi Rahman, a pediatric hospitalist and educator at the Keck School of Medicine at USC in Los Angeles to expand the scope of the work and to add educational and professional rigor to it. We have started www.artandmed.com with a full list of talks and workshops and interviews with artists-patients being added all the time.

Resources

An article about Meyer’s work with the UCLA School of Medicine:

Frank P. UCLA Medical School’s ‘guest artist’ is helping to teach doctors about disease. The Huffington Post. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2015/05/20/ted-meyer-geffen-medical-school_n_7325072.html. Published May 20, 2015.

An episode of Storycorps featuring Meyer and his friend Brian Knappmiller:

Gonzalez S. Ted Meyer and Brian Knappmiller. Storycorps. http://www.kcrw.com/news-culture/shows/storycorps/ted-meyer. Published December 12, 2011.

An article about Meyer’s work: Kennedy R. Artist celebrates scars’ fierce beauty. The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2006/10/04/arts/design/04scar.html?pagewanted=all&_r=2&. Published October 4, 2006.

An article and video through a PBS affiliate about Meyer’s work:

McArthur M. Triumphs over trauma: the scar prints of Ted Meyer. KCETLink Mediagroup. https://www.kcet.org/shows/artbound/triumphs-over-trauma-the-scar-prints-of-ted-meyer. Published October 25, 2013.

Ted Meyer’s Personal Website:

www.tedmeyer.com

Robert Frost was one of the most well-known and widely read American poets, writing realistic depictions of rural life in early twentieth century New England. He received four Pulitzer Prizes for Poetry, the Congressional Gold Medal, and was named Poet Laureate of Vermont

Robert Frost was one of the most well-known and widely read American poets, writing realistic depictions of rural life in early twentieth century New England. He received four Pulitzer Prizes for Poetry, the Congressional Gold Medal, and was named Poet Laureate of Vermont

Member since 2019 | JM14274

Member since 2019 | JM14274

NO COMMENT