Wit — A Film Review, Analysis and Interview with Playwright Margaret Edson

By S.A. Larson, Doctoral Student

A Note on the Review

Although this review will focus on the 2001 HBO film adaptation, instructors have two mediums to choose from when considering how to incorporate Wit into the classroom: the 2001 adaptation of the play (available for free on Youtube) and Margaret Edson’s 1993 stage play of the same name (available at most libraries and for purchase through online book sellers).

Resources:

Nichols, M. Wit [Movie]. Youtube. https://youtu.be/u0PPvYlGqL8. Published May 3, 2013. Accessed July 6, 2015.

Edson, M. Wit. New York: Faber and Faber, Inc.; 1993.

Film Summary

“You have cancer.” These are the words that open the 2001 HBO adaptation of Margaret Edson’s Pulitzer Prize-winning stage play, Wit. The adaptation, directed by Mike Nichols and starring Emma Thompson, tells the story of Dr. Vivian Bearing’s final weeks of life as she undergoes eight months of rigorous, and often painful, experimental treatment for Stage IV metastatic ovarian cancer.

In the film, Dr. Vivian Bearing is an accomplished professor and scholar of seventeenth century poetry. Despite her success, she has lived a life of isolation, seeking company among books rather than her peers. Her isolation leads her to seek solace in the viewer. Throughout the film she speaks directly to the camera (a stand-in for the viewer), confessing, reflecting, and even bantering to the viewer behind the lens.

The film’s opening scene progresses at a rapid pace. In terse, sober dialogue Dr. Harvey Kelekian diagnoses Professor Bearing. Less than a beat later Dr. Kelekian begins explaining an experimental research protocol. Shocked from the sudden blow of her diagnosis, and not having had time to fully process the situation and assess her options, Dr. Bearing agrees to participate, hesitantly glancing down at the first page of the protocol before signing her name.

Because she is part of a clinical study, the film is set in a research hospital and focuses on Professor Bearing’s musings, reflections, and flashbacks as well as her interactions with her primary care providers. After the diagnosis scene, the viewer is introduced to Professor Bearing’s other contrasting primary care providers: the bumbling, awkward, research-minded resident, Dr. Jason Posner and the patient-focused nurse Susie Monahan.

The film also introduces a number of characters through a series of flashbacks. These scenes transport Professor Bearing through time and space. In a central flashback Professor Bearing returns to her time as a timid undergraduate being chastised by her professor, the prolific scholar of seventeenth century poetry, Dr. E.M. Ashford. It is in this scene that the semicolon, which provides a framework for the development of the major themes of the play and insights into each character, is first introduced. Through scenes portraying various aspects of clinical evaluations, medical tests and cancer treatment, the film artfully crafts the identity of the characters pulling the viewer toward a deeper understanding of each person’s struggles individually and with each other as the film progresses.

After a stepwise and measured decline, Professor Bearing’s life ends in a moment of chaos. This climatic final scene vividly portrays each characters’ reckoning with their own sense of self. Despite her “do not resuscitate orders (DNR)”, Dr. Posner calls a code when he discovers her heart has stopped. With a final emphasis on the disconnection between medical provider and patient, the viewer realizes that the resident’s resuscitation attempts are motivated by the desire to prolong his research rather than by any emotional connection to Professor Bearing. In contrast, the quietly confident Nurse Monahan (the only care provider who assumes the patient advocate role) rises up courageously against the medical team’s ill-fated efforts and forcefully cancels the code. The film ends with the camera zooming in on the heavily lighted face of Professor Bearing’s corpse, then slowly fades into a black and white photograph of Professor Bearing at a time prior to her cancer diagnosis, wearing a slight grin, her eyes open, leaving the viewer with an image of a woman finally unburdened by her bodily struggles with cancer, who has accepted her vulnerabilities and the care and comfort of others.

“Nothing but a breath”: The Significance of the Semicolon in Wit

Wit is not a story of survival. Instead, the film deconstructs the typical tale of staying strong through cancer treatment, overcoming the odds, and surviving. The film skillfully constructs a story of repair and restoration of the individual not through treatment of the body ravaged by cancer, but by admitting one’s weaknesses, exposing oneself, and, perhaps most frightening of all, relinquishing control and, in the process, becoming vulnerable. In the end, one is left with the feeling that the main character of the play is being “healed, not cured” (M. Edson, Personal Communication, March 13, 2015).

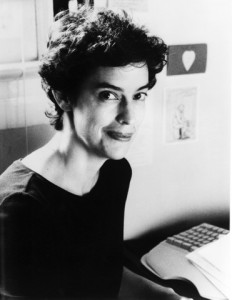

On March 13, 2015 we sat down with Margaret Edson, the playwright whose 1993 stage play, Wit, served as the source material for the 2001 HBO film in her home to discuss her play and the subsequent HBO adaptation. Reflecting on her writing, Edson characterized Wit as a struggle between herself and her creation, Dr. Vivian Bearing. While Edson relinquished creative control over the film adaptation of her work, the film still retains this conflict between character and creator through the use of flashbacks that often interrupt the present hospital setting of the play. In these scenes, Professor Bearing seems to wrest control from Edson and become the director by staging the action and interjecting her own commentary. According to Edson, “We understand as much as our previous experience prepares us for.” Rather than admitting that she is feeling vulnerable, or does not understand what is happening in the hospital environment, Professor Bearing uses flashbacks to cope with the unfamiliar and regain her power by situating the unknowable present in the knowable past.

Professor E.M. Ashford dramatically explaining the importance of punctuation in John Donne. Photo Credit: HBO Films, 2001

One particularly striking flashback occurs shortly after Professor Bearing has been diagnosed with an advanced stage of cancer by Dr. Harvey Kelekian, her attending physician, and has consented to participate in an experimental treatment. This is the first step in Professor Vivian Bearing’s shift from a position of comfort in her identity as a “doctor of philosophy . . . a scholar of seventeenth century poetry” who has “made an immeasurable contribution to the discipline,” to the unfamiliar and uncomfortable position of patient and specimen. Professor Bearing contextualizes this discomfort by remembering the early uncertainty she felt as an undergrad interacting with her professor, the renowned senior scholar of Metaphysical Poetry, Dr. E.M. Ashford. Using an “inauthentically punctuated” translation of John Donne’s “Holy Sonnet Six” she misinterprets Donne’s famous line: “And death shall be no more, Death thou shalt die” and is chastised for her unscholarly work. In the edition Professor Bearing’s version uses, the poem is punctuated by a semicolon while in the “authentic” and correct version used by Dr. Ashford, the poem simply uses a comma. This seemingly trivial difference in punctuation produces deep insight into the larger theme of the play and is beautifully articulated by Professor Ashford in the following lines:

Nothing but a breath–a comma–separates life from life everlasting. It is very simple really. With the original punctuation restored, death is no longer something to act out on the stage, with exclamation points. It is a comma, a pause.

This way, the uncompromising way, one learns something from this poem, wouldn’t you say? Life, death. Soul, God. Past, present. Not insuperable barriers, not semicolons, just a comma.

Professor Ashford’s proclamation describes Professor Bearing’s own struggle with her humanity and her mortality. She has worked so hard to conceal her vulnerabilities that passing into a state where she does admit her weakness and humanity seems like an insuperable barrier comparable to the semicolon Professor Ashford discusses. Thus, when Professor Bearing begins her treatment, she views death and weakness as adversaries that she must fight against. Even though she has had to leave her job as a professor, is in severe pain, and alone, she maintains a strong front by demonstrating her intelligence through wit. It is not until the end of the play, after she has been almost entirely broken that she finds a moment of clarity and realizes that “insuperable barrier,” the one she has been struggling with her entire life and throughout treatment is a simple comma, a simple acknowledgement of one’s humanity through raw vulnerability.

Professor Bearing’s moment of clarity is not grand or epic. Indeed, it is a simple moment painted with touches of childhood. In this scene, which takes place toward the end of the film, Professor Ashford pays Professor Bearing an unsolicited visit. A light, peaceful lullaby-like melody plays in the background. Shortly after the arrival of her old mentor, Professor Bearing quite literally takes a breath, pauses, and transitions from her guarded, isolated state to one where she is fully exposed. This moment occurs when Professor Bearing admits, after a pause and then a long exhalation, “I feel so bad” and lets roll a single tear. For the remainder of the scene she is completely exposed in her vulnerability. This scene is free of wit and displays of intelligence. Instead, Professor Bearing whimpers, and allows Professor Ashford to comfort her. Thinking she will find solace, as always, in the classics, Professor Ashford offers to recite one of Donne’s sonnets. However, now that Professor Bearing is vulnerable, without any pretenses or façade to maintain, she refuses the offer and instead welcomes Professor Ashford’s reading of the children’s book The Runaway Bunny.

Professor Bearing’s moment of vulnerability is directly related to her death. In the scene that follows, Dr. Posner discovers that Professor Bearing is dead. There is no transition between her scene with Dr. Ashford and the discovery of Professor Bearing’s corpse. In fact, much like Professor Ashford’s meditation on commas and death, Professor Bearing, after her moment of vulnerability, passes from life to death off screen (not acted out on stage), free of drama. It is only after she accepts her humanity and weakness that she can also accept her mortality.

Although Professor Ashford is discussing life and death, her words have a powerful tie to the world of rehabilitation medicine and would be useful for students to evaluate. While the end result of rehabilitation therapy is often a larger goal, the day-to-day clinician-patient interactions center on small achievements and using those small steps to progress to the larger goal. Patients and clients are not attempting to “overcome the seemingly insuperable barriers” in one step, but rather, are focusing on the daily small goal of passing beyond the point of the comma.

The Platinum Rule: Patient and Care Provider Interactions

Wit is more than a case study of an individual struggling with experimental cancer treatment and, in the process, her humanity. The play also depicts Professor Bearing’s interactions (or lack thereof) with her primary care providers Dr. Harvey Kelekian, Dr. Jason Posner, and Nurse Susie Monahan.

A still from the Grand Rounds scene in which Professor Bearing’s body is used as a text. Photo Credit: HBO Films 2001

With her characteristic dry wit, she reflects on the depersonalized nature of the hospital: “in Grand Rounds, they read me like a book. Once I did the teaching, now I am taught.” Despite Professor Bearing’s seemingly compulsive need to repeat her credentials to herself, in the hospital, and in the world of research she admits that “What we have come to think of as me is, in fact, just the specimen jar, just the dust jacket, just the white piece of paper that bears the little black marks.”

Through her series of flashbacks, Professor Bearing gradually becomes aware that she is guilty of the same inhumanity that readers are so apt to critique her primary care providers for exhibiting. In a sense of new self-awareness, she contextualizes Dr. Jason Posner’s view of patients as specimens with a scene in which she, herself, fails to appreciate or even recognize the humanity of her students. Ultimately, she realizes her behaviors as a professor were not that much different than those she is experiencing from her medical team.

In our interview for JHR, Edson described the essential nature of the human interaction between patient and clinician when she reflected on her own job as an aide in the physical therapy department of a community hospital, and as a physical therapy patient after separating her shoulder: “What makes me believe that I can try? It is my relationship with you. That really is all that I have. You make me feel that way – that I can try” Edson believes that Nurse Monahan successfully practices such a relationship ethic with Professor Bearing. While she may not have the academic intelligence of the research doctors or the scholarly and accomplished Professor Bearing, she is the backbone of the research hospital due to her combined skill and sensitivity.

While most are familiar with The Golden Rule (Treat others the way you want to be treated), Edson, in our interview, invoked The Platinum Rule (Treat others the way they want to be treated) and its importance in patient-clinician interactions. Nurse Monahan seems to best embody The Platinum Rule in the film adaptation of Wit. Rather than dehumanizing or patronizing Professor Bearing, Nurse Monahan seems to empathize with her patient. She seems to anticipate her patient’s needs, and the way Professor Bearing herself would wish those needs to be fulfilled.

Nurse Monahan and Professor Bearing sharing a deeply personal moment while discussing “Vivian’s” DNR. Photo Credit: HBO Films, 2001

Extracting this theme of human interaction from the play, Wit can be used to challenge students to examine the effects of their interactions with others in the classroom, clinic, and community. How do we address our patients? Can a simple choice of words actually influence our interactions to such an extent as to impact our therapeutic outcomes? For example, Students could examine the way Dr. Kelekian and Nurse Monahan each address Professor Bearing and how their respective addresses could influence patient-primary caregiver interactions. From one of the introductory scenes in the film, Dr. Kelekian addresses Professor Bearing as Dr. Bearing rather than using her first name. This act of professional respect is a silent acknowledgement of the rigor of their respective fields, their shared dedication to their scholarship and creates a collegial intimacy that drives their relationship throughout the play. In contrast, Nurse Monahan begins her relationship with Professor Bearing by using the respectful address of “Ms. Bearing.” It is not until Professor Bearing reaches the end of her life that she and Nurse Monahan shift their addresses to one another to the more significant and intimate “Vivian.”

Students could also trace the way Professor Bearing’s interactions with her three primary caregivers are depicted. They can critique each interaction, compare and contrast them, and perhaps even take the time to rewrite the way they would have handled the interaction had they been in the primary caregiver’s position.

“Pressing to the edge”

Interestingly, Edson shared that her first job was as a physical therapy aide. When reflecting on this early work, Edson observed, “The world of physical therapy, it seems to me, is incremental progress; is small steps, small improvements toward a distant goal.” Throughout the play Professor Bearing’s transformation into a human who has lived and is willing to admit her vulnerability is achieved through a similar series of small steps through a form of what Edson calls spiritual physical therapy. According to Edson, by the end of the play, Professor Bearing has been “pressed to the edge of what she feels safe doing and then has to do one more thing. And that’s where we grow, at the margin there, at the zone of discomfort. If there’s too much of that destabilization, then we retract, but if there’s the right amount that’s where our growth comes.” Nurse Monahan, who, with her gentle patience stands steadfastly by her side, becomes that clinician who pushes Professor Bearing just enough to help her grow. Their relationship allows for Professor Bearing to realize that truth that Edson describes: “the risk of your own weakness is the beginning of your own increase of strength.”

Practitioners, Patients, and Playwrights

“Physical therapy is such a dialogue; it’s just the two of you and you’re talking about it and you’re doing it together.”

According to Edson, “Studying theater is the best way to see what it’s like to be somebody else; to pretend to be somebody else.” By incorporating playwriting and acting into the PT curriculum, faculty can help students explore their growth as clinicians, grapple with their mistakes, and even gain a better sense of empathy and understanding for their patients.

Instructors can incorporate a multimedia approach to Wit by asking students to read a scene from the stage play and then watch the same scene from the film. In a simple compare-contrast exercise students can pair up and examine the differences and similarities between both mediums. Students can use this analysis to start a dialogue about the different insights they gained from the different mediums.

Improv is a low-stakes introduction to acting and playwriting for PT students. Students can take turns occupying certain roles such as: patient and practitioner, practitioner and a patient’s family member, and practice presenting unscripted interactions in front of the class. This short exercise would challenge the acting students to think from new perspectives while also giving the class the opportunity to give feedback on the scene.

Edson suggests asking students to read various scenes from Wit, occupying different roles with each reading followed by a discussion of how their feelings and understanding of the situation changes with each character. There are two scenes in particular that lend themselves well to this exercise in empathy. The first, known as the “Popsicle Scene” occurs toward the end of the play when Nurse Monahan and Professor Bearing discuss code status. The second scene opens the play and depicts the interaction between Dr. Kelekian and Professor Bearing the moment she receives her initial diagnosis and makes the decision to sign on for an experimental research protocol.

Edson believes that actual playwriting can challenge students to become better listeners and more empathetic clinicians. “What playwrights do is imagine what other people say, imagine the thoughts and utterances of other people. And that’s what compassion is.” By asking students to write a scene in which they interacted with a patient, they will be forced to recall what their patient said and help to explore new strategies to improve listening skills. Further, by writing from the perspective of their patients, students are given practice empathizing with others. They must remove themselves from the authoritative position of clinician and truly feel what it is like to be the person on the receiving end of that knowledge.

Students can use playwriting to chart their progress as clinicians by composing a scene in which they consider how they would act in a certain patient situation before going on clinical rotations, then reconsider the scene after they have gained clinical experience, reflecting how they actually experienced that patient interaction. This style of writing can be an effective tool for students to grapple with challenging or disappointing situations during the clinical rotation. One of the most dreaded questions that one can ask is “Tell me about a time when you made a mistake.” Playwriting offers a creative approach to facilitate this reflection with students, asking them to compose a scene in which they reenact that mistake. To give students a clear perspective of the event, the scene should be composed using a stand-in character in place of the student herself. The instructor could then distribute the scenes to students who did not write the play and ask them to take turns performing the mistake as both the clinician and patient. During these performances the players, writer, and audience could work together remedy the situation thus making this a learning experience for the entire class.

In all, playwriting holds the potential to help students build a community in which they share and engage with one another’s work and in the process learn from the experiences of their peers.

Biography of Margaret Edson

Margaret Edson was born in Washington, DC in 1961. Between earning degrees in history and literature, she worked as a unit clerk on the cancer and AIDS in-patient unit of a research hospital. Wit, written in 1991, is her only play. Edson has been a public schoolteacher since 1992. She currently teaches sixth-grade social studies in the Atlanta Public Schools.

Timeline of Wit Productions and Awards

Wit was written in 1991 and first premiered at South Coast Repertory, Costa Mesa, California in 1995. It was produced in New York in 1998 and received the Pulitzer Prize for Drama in 1999. The HBO production, featuring Emma Thompson, won the Emmy Award for best film in 2001; it is now available on You Tube. Wit was revived on Broadway in 2012, with Cynthia Nixon in the lead role. The play has received hundreds of productions in dozens of languages. The text is widely used in teaching, ranging from high- school English to graduate bioethics seminars.

Member since 2019 | JM14274

Member since 2019 | JM14274

NO COMMENT