Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec: Disability and Art in Fin-de-Siècle Paris

By John David Ike, MD Candidate, Emory University School of Medicine

Count Henri Marie-Raymond de Toulouse-Lautrec-Montfa, more commonly known as Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1864-1901), was a French-born artist renowned for his depictions of the bohemian life in Montmartre in fin-de-siècle Paris. Born into a noble family in the south of France, Lautrec was the last of a bloodline who claimed descent from Henry IV of England and blood-relation to Charlemagne, the former Holy Roman Emperor of France.1 While Lautrec’s childhood was marked by social and financial wealth and good fortune, in early adolescence he suffered two significant fractures of his left and right femurs in quick succession. Following these injuries, Lautrec’s growth was significantly stunted, leaving him permanently disfigured, crippled, and unable to participate in the bourgeois activities his family enjoyed, namely hunting and horseback riding. As a result, Lautrec turned to the arts, eventually becoming one of the most important documentarians of late 19th century in Paris working alongside Edgar Degas and Vincent van Gogh. Perhaps his most significant contributions were his original and iconic lithograph posters for various dancehalls throughout Montmartre, and his intimate oil paintings of the working-class prostitutes and the aristocrats who frequented these lively venues.

Fig. 1: Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1864-1901) painting the portrait of Berthe la Sourde in the garden of Père Forest in Paris. 1892. Image credit: Art Resource, New York.

The underlying pathology of Lautrec’s fractures has been highly debated among scientists and medical professionals. After numerous discredited diagnostic proposals and without post-humous genetic testing, the current accepted theory proposed by Maroteau and Lamy in 1962 is that Lautrec suffered from pycnodysostosis, a rare autosomal recessive lysosomal storage disease of the bone associated with short stature despite normal truncal height, pathologic bone fractures, a hypoplastic mandible, a deformed cranium, and a range of other abnormalities.2 These clinical features align with Lautrec’s known physical attributes, most notably his disproportionate short stature, his receding mandible (which he attempted to hide with facial hair), and his cranial deformities.1,2 Several of these features are visible in a photograph of Lautrec painting en plein aire – a technique championed by the Impressionists – at his neighbor’s house in Montmartre in 1892 (Fig. 1).

Lautrec’s physical limitations had a significant impact on his internal psyche. Lautrec first mentions his disability in a letter to his mother when seeking medical treatment in Paris in 1875 at the age of eleven: “Dr. Vernier was very satisfied with my legs. When you return, I hope you will find me well.”1 It is important to note that this letter was written prior to his devastating fractures. Nevertheless, the effect of his disease on his internal emotional state prior to his fractures is palpable in a letter written by Lautrec’s grandmother around the same time: “The humidity doesn’t particularly trouble Henri, and now that the weather is so mild, he can go for long rides … with such a high spirited fellow around, how could we persist being so gloomy?”1 While Lautrec’s spirits and intellect remained vibrant throughout his life and working career, his poor health resulted in a significant blow to his morale. In a private letter to a friend during a prolonged period of bedrest, Lautrec wrote the following about his cousin, “I began to wonder whether Jeanne d’Armagnac will come and sit by my bed. She does come sometimes and I listen to her but lack to courage to look at her, who is so beautiful and tall, and as for myself – I am neither of these.” 1 Despite his disability, Lautrec feverously pursued his art, moving to Paris in 1882 at the age of eighteen to begin his formal training.

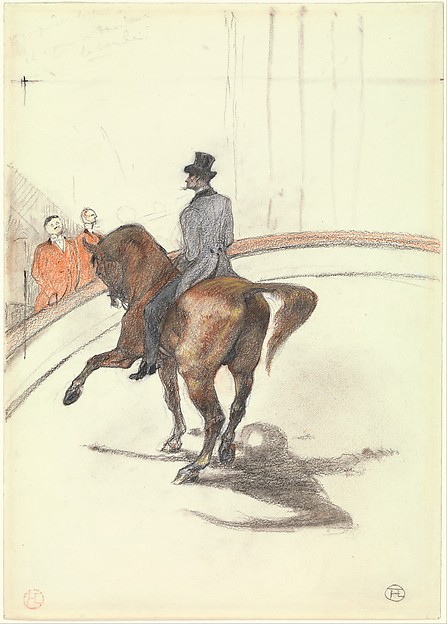

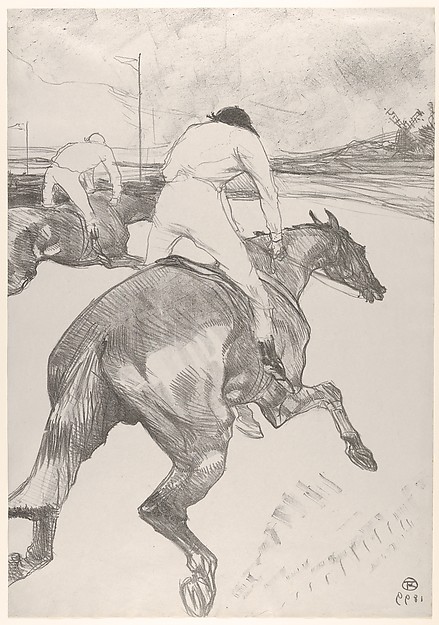

Shortly after arriving in Paris, and with future hopes to join the famed École des Beaux-Arts, Lautrec continued his study under Rene Princeteau, a portrait painter who began tutoring Lautrec in the early-to-mid 1870s. Princeteau, who was partly deaf and mute, fortified Lautrec’s love of horses with frequent trips to the circus where they concentrated on draftsmanship and the portrayal of horses in motion.2 Evidence of these trips can be seen much later in his career in two sketches: The Jockey and At the Circus: The Spanish Walk (Fig 2, Fig 3). Both works pay homage to Lautrec’s continued admiration for his former teacher and illustrate his technical skill as a draftsman. Yet, Lautrec quickly realized that Princeteau’s instruction was insufficient and he transferred to Léon Bonnat’s studio, and shortly thereafter to Fernand Cormon’s atelier. An easy-going artist, Cormon’s atelier provided Lautrec and his pupils (which included Emile Bernard) with a club-like atmosphere to explore their artistic interests. It was during this time that Lautrec befriended Edgar Degas and Vincent van Gogh.

Fig. 2: At the Circus: The Spanish Walk. Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. Graphite and pastel on paper. 1899. Image credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Fig. 3: The Jockey. Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. Lithograph on China Paper. 1899. Image credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Degas’ work had a profound impact on Lautrec’s artistic vision. Like Degas, Lautrec focused on the female form and the intimacies of the feminine toilette. Moreover, Lautrec’s friendship with van Gogh – that between a physically disabled young aristocrat who favored brothels and the emotionally unstable son of a Dutch pastor who also frequented cafés – further solidified Lautrec’s appreciation for vivid color and the Japanese print, which utilized geometric shapes and flat areas of color to portray its subjects. By 1886, a time when many artists in Cormon’s studio and contemporaries were leaving Paris (Gauguin and Bernard traveled to Britanny and van Gogh traveled to Arles), Lautrec remained and acquired his own studio on Rue de Caulaincort in Montmartre. Within a few years, Lautrec’s lithographs and oils, inspired by the eclectic culture and nightlife of Montmartre, rocketed him to stardom in the Paris art scene.

Situated on a hill on the outskirts of Paris, Montmartre began as a rural village dotted with windmills that over the course of the 19th century was annexed by the city of Paris and became a preeminent working class neighborhood.3 Retaining its narrow and winding streets, steep elevation, and historic charm, Montmartre was divided into two separate districts – the lower slopes which were inhabited by wealthy artists (Degas, Moreau, Renoir) and aristocrats, and an upper “butte” inhabited by working-class Parisians and bohemians.3 The Moulin Rouge dancehall, which opened in 1889 and was situated at the intersection of the upper butte and lower slopes, along with many other cafés in Montmartre quickly replaced the Left Bank’s Latin Quarter as the intellectual and artistic hub of Paris.3 Nicole Myers, an art historian at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, commented that “[Montmartre’s] performance halls provided a rare opportunity for the mixing of social classes, particularly between bourgeois men and working-class women, whose interactions were often based on prostitution. The blurring of class boundaries contributed to Montmartre’s reputation as a place for escape, pleasure, entertainment, and sexual freedom.”3 It was in this morally and culturally unburdened environment that Lautrec lived and worked with evening visits to the dancehalls and cafés to drink, socialize, and sketch. Lautrec’s early success in Montmartre was the result of his innovative lithographic posters commissioned by the various dancehalls and cafés.

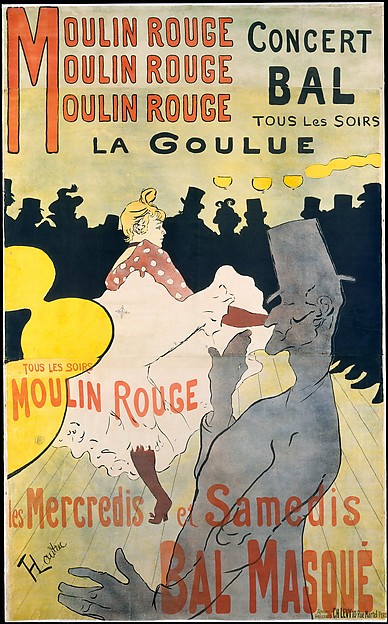

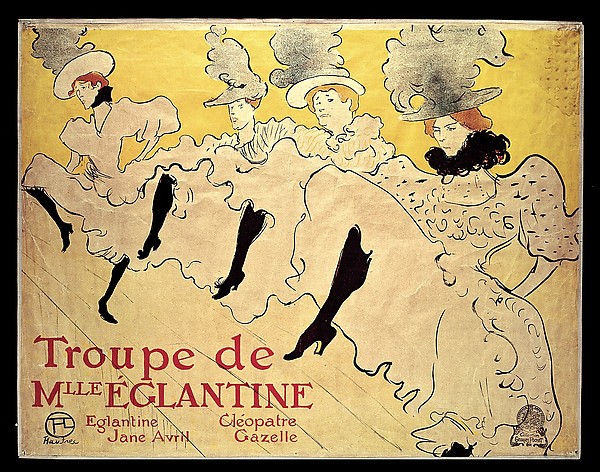

Lautrec’s first significant commission, Moulin Rouge: La Goulue, a six-feet tall lithographic poster for the Moulin Rouge nightclub in 1891, led to significant recognition among artists and non-artists alike (Fig 4). With inspiration from the Japanese woodblock print, Lautrec’s Moulin Rouge: La Goulue was avant-garde in its incorporation of impressionistic techniques and its utilization of the technological advancements in printmaking, namely the commercialization of the lithograph. The poster portrays the fluid dancing of La Goulue (The Glutton), the nightclub’s most renowned young female can-can dancer whose skirt would be lifted at the conclusion of act, and an anonymous middle-class male patron outlined in black. The sexual tension and psychological interaction between the anonymous male patron and vibrant female dancer reinforced the moral and ethical trends in Montmartre and the diversity of the dancehall’s patrons.3 Another of Lautrec’s well-known lithographic posters, La Troupe de Mademoiselle Eglantine, similarly captures the fluidity of the dance through a dynamic interplay between bold line and a flat, yet vibrant color scheme (Fig 5). Lautrec’s ability to capture and portray harmonious movement in his work is all the more significant when considering Lautrec’s own physical limitations.

Fig. 4: Moulin Rouge: La Goulue. Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. Lithograph. 1891. Image credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art.

La Troupe de Mademoiselle Eglantine. Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. Lithograph. 1895. Image credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art.

While Lautrec’s posters led to his initial celebrity, his oil paintings solidified his position as the preeminent artist of the bohemian culture in Montmartre through their grandiose and honest depictions of working-class life. The Public Ball (mid-1890s) demonstrates Lautrec’s power as an observer (Fig 6). Using a strong diagonal in the foreground (a compositional technique borrowed from Degas), Lautrec creates a physical boundary and an emotional tension between the dancing patrons in the background and the bored working-class women in the foreground. Moreover, his hurried brushwork and decision to thin the oil paint with turpentine to create a translucent effect (a technique known as peinture à l’essence) reinforces the fleeting nature of relationships and interactions amongst patrons and prostitutes.4 The vantage point of the painting is also significant as it is likely the perspective Lautrec, given his physical disability, would possess during his evening trips to the dancehalls.

Fig. 6: “La Moulin de la Galette.” Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. Lithograph. 1890s. Image credit: Art Resource, New York.

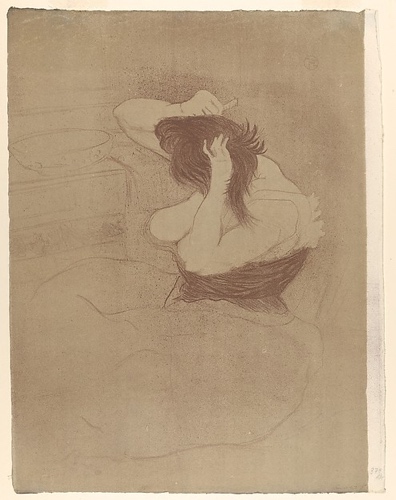

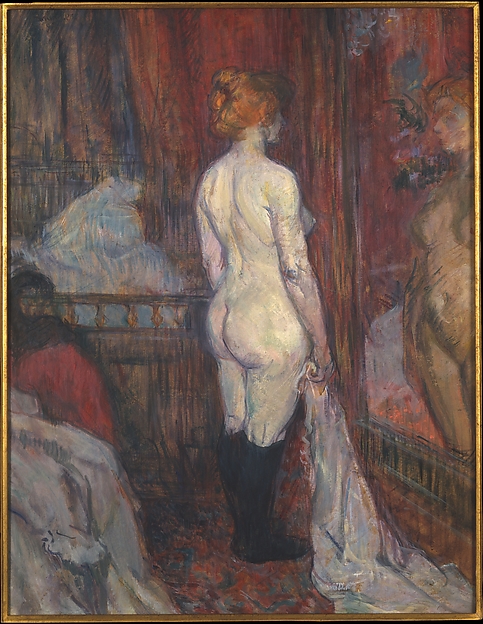

Lautrec’s oil paintings extended beyond the dancehall to more intimate spaces, primarily the dressing rooms of the prostitutes whom he befriended. While his drawings of working-women preparing for their evening clients (Woman Combing Hair) demonstrate Lautrec’s friendly relationships, his oil paintings, notably Woman before a Mirror, illustrate his profound understanding of their psychosocial condition (Fig 7, Fig 8). Standing naked before a mirror, the woman’s internal psychological state is ambiguous while her physical form is concretely defined and explored artistically. There is an intimacy and brutality that challenges the viewer to question their own gaze as well as their predisposed conclusions. As Cora Michael, an art historian at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, posits, “Lautrec presents her neither as a moralizing symbol nor a romantic heroine, but rather as a flesh-and-blood woman (the dominant whites and reds in the composition reinforce this reading), as capable of joy and sadness as anyone.” 5 His oil paintings challenged the established doctrine of the time and granted a level of prestige to the working-class women of Montmartre typically reserved for the aristocratic class. Perhaps Lautrec’s own physical limitations and personal vices enabled him to not only befriend, but uniquely understand and portray the variable psychosocial circumstance of his subjects.

Fig. 7: Woman Combing Hair. Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. Lithograph on two woven papers. 1896. Image credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Fig. 8: Woman Before a Mirror. Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. Oil on cardboard. 1897. Image credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec’s career lasted a little over a decade with his most productive period occurring from the late 1880s to an untimely hospitalization in 1899 for delirium tremens, a complication of chronic alcoholism. Lautrec used the horse sketches mentioned earlier in this article to demonstrate to his physicians that he was safe to return to Paris to resume his work as an artist.1 But his return to Montmartre was rocky and within a few months Lautrec was consuming copious amounts of alcohol and began to suffer neurologic complications of syphilis, a venereal disease he contracted in 1888 as a result of his sexual relationships with prostitutes. In 1901, Lautrec suffered a seizure complicated shortly thereafter by a stroke which left him incapacitated. He died a few days later in Malrome, France, three months prior to his 37th birthday. His unique ability to capture the vibrancy and fluidity of 19th century French bohemian culture as well as his intimate depictions of the ambiguity and emotional isolation of the working-class women of Montmartre cement Lautrec’s legacy as the preeminent documentarian of “the naughty-nineties.” His physical disability and vibrant personality likely enabled him to effortlessly navigate this bohemian underworld with ease; an artist whose own physical wounds offered him a unique insight into the psychological condition of his subjects.

References

- Cawthorne T. Toulouse-Lautrec–triumph over infirmity. Proc R Soc Med. 1970;63(8):800-805.

- Herbert JJ. Toulouse Lautrec. A tragic life; an inspired work; a difficult diagnosis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1972;89:37-51.

- Myers N. The Lure of Montmartre, 1880-1890. Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. 2007.

- Permanent Art Collection Label. Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec – Moulin de la Galette. Chicago Institute of Art: Chicago Insitute of Art; 1886.

- Michael C. Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1864-1901). Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. 2010.

Member since 2019 | JM14274

Member since 2019 | JM14274

NO COMMENT