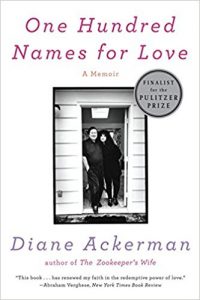

Bringing Therapy Home: Book Review of One Hundred Names for Love

By Julie Hengst, PhD, CCC-SLP

In One Hundred Names for Love: A Stroke, a Marriage, and the Language of Healing,1 Diane Ackerman[i], a well-known poet, essayist, and naturalist, chronicles how she and her husband, Paul West, responded to his aphasia. Paul was a prolific author and consummate wordsmith who loved languages. In 2003, Paul was in the hospital recovering from a kidney infection. Diane was visiting him when he had a massive left-hemisphere stroke. Having just written a book on brain research (An Alchemy of Mind2), she immediately recognized the signs:

In One Hundred Names for Love: A Stroke, a Marriage, and the Language of Healing,1 Diane Ackerman[i], a well-known poet, essayist, and naturalist, chronicles how she and her husband, Paul West, responded to his aphasia. Paul was a prolific author and consummate wordsmith who loved languages. In 2003, Paul was in the hospital recovering from a kidney infection. Diane was visiting him when he had a massive left-hemisphere stroke. Having just written a book on brain research (An Alchemy of Mind2), she immediately recognized the signs:

Paul shuffled out of the bathroom and stood at the foot of the bed, eyes glazed, his face like fallen mud. His mouth drooped to the right, and he looked asleep with open eyes that gaped at me in alarm. [When Diane asked] “What’s wrong?” He moved his lips a little, making a sound between a buzz and murmur. (p. 5)[ii]

With an acute diagnosis of global aphasia, Paul’s only reliable utterance during those early days was “mem mem mem.” Diane reflected: “In the cruelest of ironies for a man whose life revolved around words, with one of the largest working English vocabularies on earth, he had suffered immense damage to the key language areas of his brain and could no longer process language in any form” (p. 18). Indeed, in those early days the outlook for Paul seemed bleak. Yet, several years later, Paul had returned not just to writing daily but also to authoring and publishing books. At the core of this remarkable recovery was a home program Diane herself designed, one grounded in her curiosity about how the brain works, in her knowledge of her husband, and in her own desire to reconstruct their life together.[iii]

Rehabilitation: The Early Weeks

One Hundred Names for Love is organized into two parts. Part One, The Cartography of Loss, opens at the moment of Paul’s stroke and continues through his inpatient rehabilitation at the hospital. Diane describes these early weeks as frustrating, confusing, and exhausting—both for her and Paul. With little understanding of what the future might hold, she was now faced with making life choices for both of them. The early diagnosis from the speech-language pathologist (SLP) included: oral apraxia and severe apraxia of speech; expressive and receptive aphasia; and dysphagia with risk of aspiration. Diane watched hopefully as Paul struggled to talk—as he gradually formed more words (although it was mostly jargon) and occasionally produced more meaningful sentences, like “I speak good coffee!” Diane struggled to find new ways of communicating with him and found that carrying on one-sided conversations was exhausting. Although Diane’s memoir focuses mostly on Paul’s aphasia, she also describes the complex disruptions caused by the stroke—his visual field cut; his problems with walking and balance; and his inability to recall and follow through on multistep tasks of everyday life such as getting in and out of bed, managing personal hygiene, and eating and swallowing. Throughout these weeks in the hospital, Paul expressed his fervent desire to go home. And Diane finally agreed. At six weeks post-stroke, she moved Paul and his rehab program home.

Rehabilitation: At Home

Ackerman devotes more than half the book to Part Two, A House Made of Words. Here she describes their time at home and her realization that she would have to take charge of Paul’s rehab program. Diane refused to accept the bleak prognosis for Paul’s future. She was buoyed by a visit from their acquaintance, well-known neurologist and author Oliver Sacks, who counseled them not to listen to doctors who said there was only a short window of opportunity for improvement, noting: “You can continue to improve at any time, one year, five years from now. … I have a relative who kept making important improvements ten years after her stroke.” (p. 119). From her study of the brain, Diane knew that, to prompt his brain cells to grow more connections and the right connection, Paul needed an enriched environment (every bit as much as the lab rats who thrived in enriched cages). Thus, she set out to drench Paul in meaningful language and meaningful routines.

To help achieve this drenching, Diane hired an assistant, Liz, a nurse who had “the gift of gab” (p. 158). Liz’s job was not only to help Paul with his daily care (such as managing his insulin and preparing meals), but also to talk with him all day, every day. During her daily visits, Liz engaged Paul as an audience to her stories, regaling him with updates on the nefarious exploits of Gustaf (her neighbor) as well as more mundane stories about her own trips and past jobs. When Paul was too tired to fully listen, Liz and Diane would chatter together to pass the time, allowing Paul to be a peripheral participant in their back-and-forth banter. At other times Liz would create on-the-spot word games with Paul, trying to impress him with her new medical knowledge:

“I have a word for you,” she’d say teasingly or as though she was bearing a gift. “Do you know anhedonia?” …

[or]

“Wanna hear about the four major types of prostate surgery?” (p. 205).

Liz would also lure Paul into talking by asking about things she saw around the house:

“In the library, there’s a photo of you and Diane standing next to another couple in front of a little plane. It’s a neat photo. Where were you going?” (p. 206).

Such inquiries would launch a series of exchanges as they worked together to uncover the details about the object—with Paul remembering key words and Liz successfully guessing or Liz ending the search by saying, “We’ll ask Diane.” (p. 208).

Diane described numerous ways she worked to reshape their home and reinvent daily routines that could accommodate Paul’s new ways of navigating physical spaces, decrease his dependence on her for routine activities, and minimize her concerns for his safety. They installed raised toilet seats, bought him an electric razor, and made certain areas of the house (such as the kitchen stove) off-limits. “So much now dumbfounded him, especially household gadgets,” (p. 137), Diane recalled. She also worked to minimize his daily frustrations, adding brightly colored dots to the buttons he routinely used on the remote control for the television and the control panel for the microwave oven. To help prevent him from falling, she hired people to install a railing in the garden to make it easier for Paul to get safely to the swimming pool on his own. Paul met with the men to make sure the railing height was just right.

With each of her decisions, Diane pursued her goals of helping Paul participate in life and above all to reconnect with his love of language. By engaging him so intensely in meaningful communication and by supporting all of his spoken and written attempts, Diane pushed Paul to be creative and playful with the words he did produce and to savor them all. When she suggested, at only two months post-stroke, that Paul start working on his own memoir of aphasia, he agreed. Liz’s role then expanded to that of literary assistant, taking dictation at first and later helping edit his written drafts.[iv] His memoir of aphasia, The Shadow Factory,5 was published in 2008.

On another occasion, Diane heard Liz casually ask Paul if he had pet names for his wife. Crestfallen, he replied:

“Used to have…hundreds,” he said with infinite sadness. “Now I can’t think of one.” (p. 249).

So, Diane challenged Paul to make up new names for her, and he responded by greeting her every morning for one hundred days with a new imaginative nickname—Celandine Hunter (celandine is a yellow-flowering poppy that has been used as an herbal medicine); Swallow Haven; Spy Elf of the Morning Hallelujahs; and 97 more. [v] It is this playful activity of devising a new repertoire of romantic nicknames that gives the book its title, One Hundred Names for Love.

Therapy Mismatches

After Paul’s discharge from the hospital, Diane had arranged for him to continue his daily speech therapy sessions at home, but found that what happened in those few hours a week was far from enough to overcome his aphasia and too often misaligned with Paul’s interests and experiences. Diane reflects on how his SLP sessions at home mirrored his early sessions in the hospital. Quick to correct and reshape his immediate aphasic errors, SLPs often missed what was creative in Paul’s multilingual labels and more playful responses. Diane describes one session when Paul was naming items in artwork postcards that she had given the SLP to use along with her flashcards. Diane was watching as Paul grappled with the cards, “most of which left him speechless or uttering the wrong words.” When they got to one showing Raphael’s famous painting of two baby angels leaning on chubby elbows over a balcony, Paul said, “Chair-roo-beem.” The SLP patiently corrected him, “No, … these are angels, AINGELS” (p. 191). Diane found herself explaining that cherub is a word for a baby angel, and cherubim is its plural form. Diane concluded that both the therapists and the therapy tasks were a mismatch for Paul:

Many of the speech therapy exercises—matching word with object, filling in the blanks—emphasized the detailed, linear thinking that meant visiting the gaping ruins of Paul’s private hell, his damaged left hemisphere. Good practice, designed to exercise his weakest areas, they nonetheless brought a steep sense of failure. A lifelong overachiever and exceptional student, he knew that half wrong was a dismal result. And failing so miserably at simple exercises, he began to sink into a depression again. (p. 147-148)

During Paul’s early recovery, five different SLPs visited them to provide in-home therapy sessions. Diane recalls that, despite the hardworking and polite professionalism of each of the SLPs, they didn’t know Paul, and Paul disliked what he perceived to be their “condescending and too corrective manner” (p. 190-191).

Years later, during one of Paul’s too frequent hospitalizations, Diane struck up a conversation with a new doctor who was looking with pity at Paul’s recent brain scan. Although the image did not indicate any new damage, old lesions were clearly evident throughout his brain, including in the left temporal, parietal, and frontal lobes. Diane asked him, “What does the scan tell you?” The doctor responded by pointing to all the damaged brain regions evident on the scan and saying: “I’d assume this man has been in a vegetative state.” Diane responded:

“Far from it. Would you believe he’s written several books since then? That he’s been aphasic but communicative, swimming a lot, living a much more limited life, but a happy and relatively normal one.”

His face flashed in disbelief. “How is that possible?” He asked quietly, as if thinking out loud. Looking back at the scan’s deadened landscape, and shaking his head again.

“Working the brain hard every day for four and a half years since the stroke.” (p. 294)

Outcomes and Lessons Learned

Diane closes the book with two short chapters. The Epilogue gives readers a glimpse of Paul at five years after his stroke having regained much of his command of, and love for, language. In Postscript: Some Lessons Learned, Diane reflects on how their experiences redesigning their home life to work Paul’s brain hard every day resonated with many current directions in clinical research. Specifically, she highlights immersion programs, supportive and adaptable communication partners, a focus on meaningful and creative communication, and developing functional and supportive routines that recognize the often too-limited energies available to patients and caregivers alike.

Reviewer Commentary

Memoirs such as One Hundred Names for Love provide opportunities to explore the lived experiences of stroke and aphasia from the perspective of specific patients, their family members, and their everyday activities. Although Ackerman had written a popular book exploring the mysteries of the human brain and discussing developments in modern brain research, the contributions of this memoir are not in its detailed accounts of brain damage or neuroscience, and specialists may actually quibble with some of Ackerman’s use of terms. Readers should not approach memoirs as if they are textbooks, just as clinicians should not approach individual clients as if they are simply textbook examples of stroke and aphasia. What One Hundred Names for Love does offer is an evocative account of one couple’s experiences with aphasia.

The rich particulars that Diane offers about Paul’s life remind us that all clients, beyond their diagnostic labels, are unique individuals fully situated in social worlds, historical trajectories, and complex interactions between their physical abilities and environments. Memoirs can be seen as contributing to the long-standing tradition in clinical neurology of developing rich clinical narratives of the impacts of brain injuries on the lives of specific individuals.6,7

Drawing on the work of anthropologists,8 my colleagues and I have argued for the value of thick description9—that is, for interpreting disciplinary categories through the personal meanings and lived experiences of the individuals being observed. We have argued that clinical reasoning involves a specialized form of thick description that requires clinicians to understand a client’s clinical profile through a detailed understanding of the activities and practices of each client’s everyday life worlds. However, our analysis of more than 70 years of published articles documented that thick description of the lived experiences of people with acquired cognitive-communication disorders is exceedingly rare in the research literature on aphasia and related disorders. Given this general absence, memoirs such as One Hundred Names for Love can help to fill the gap and critically extend the vision of life after brain damage.

Given Paul’s remarkable recovery, the most striking contribution of this memoir (particularly for SLPs) is Diane’s detailed descriptions of the comprehensive program of language interventions that she developed for Paul at home. To tap into the power of enriched environments, Diane focused on immersing Paul in meaningful communication opportunities all day, every day; on surrounding Paul with flexible and consistent communication partners; on encouraging Paul in his creative and playful language use; and above all, on supporting Paul in re-engaging in the meaningful activities of his social and professional life. Reading her memoir, I was especially struck by how Diane and Liz’s interactions with Paul closely resembled the descriptions of client-clinician interactions in my research exploring how clinicians can work to build rich communicative environments in clinical spaces by taking on the role of interested and supportive communication partners with their clients,10 and by drawing on the power of repeated engagement with meaningful activities to prompt recovery and learning for patients with aphasia.11

In the clinical literature, Paul’s case would be treated as an outlier on the typical recovery curve—displaying an unexpected and extremely positive outcome. The challenge for clinicians and researchers alike is to resist the urge to dismiss Paul’s case as simply an anomaly, and instead to approach it with curiosity. We need to ask ourselves why Paul’s recovery was so successful and how we might work to replicate such success with other clients. Clearly Paul and Diane had advantages—such as financial and medical resources, flexible work schedules, and social networks—and no doubt Paul’s premorbid drive to achieve along with his exceptional linguistic and communicative abilities aided his recovery. However, we should not assume that these differences alone account for his success. We need to consider as well what the value is of tailoring therapy to the unique activities of specific people, of working with clients and their families as rehabilitation partners who can structure enriching environments outside of the clinic, and of developing interventions to target the flexible and creative communicative practices of everyday life, not just the predetermined linguistic productions typical of drills.

The Book as a Teaching Tool

One Hundred Names for Love is a beautiful and thought-provoking read that should prompt rich and important discussions, whether among students and teachers or among experienced clinicians and researchers. Throughout the book, Diane’s account resonated with the experiences I have heard from many individuals with aphasia and their families across my clinical and research career.

For newer clinicians, Diane’s rich portrayal of the cartography of loss brings home the confusion, fear, and exhaustion that patients and their families face during acute care as they adjust to the realities of stroke, the uncertainties of their diagnoses and prognoses, and the routines of rehabilitation programs. I have found this section to be particularly helpful in highlighting the importance of providing educational resources and communication counseling. Novice clinicians, for example, can be encouraged to discuss Diane’s evolving understandings of Paul’s condition and the educational materials and conversations that helped her along the way.

In Part Two, Diane’s descriptions of filling the house with language provide many good examples of meaningful and supportive conversational practices that Diane and Liz employed with Paul, despite his limited spoken language. Both novice and experienced clinicians will find it useful to discuss the differences that Diane describes between the playful, nonjudgmental practices of Paul’s nurse, Liz, and the corrective drills and responses of the SLPs. I have long argued that SLPs should be communication experts10—in practice as well as in knowledge—flexibly altering their communicative roles both to support each client’s successful participation and to meaningfully address diverse communication goals. Thus, for a field that has been dominated by clinician-directed models of intervention, close attention to the power of other practices and stances can be very instructive and inspiring.

Finally, discussions of the choices Diane made and Paul’s remarkable recovery should lead to provocative reflection about the goals and implementation of interventions for aphasia. The book highlights the gap between occasional therapy and a comprehensive (all-day, everyday) program. I believe that many of us have felt that too much weight is put on, too many hopes are pinned to, just a few hours of clinical therapy each week. As clinicians, this recognition could lead us to make working with clients and their families to design enriched home environments a central goal of our therapies.

Conclusion

A Hundred Names for Love —a finalist for the 2011 National Book Critics Circle Award and the 2012 Pulitzer Prize—offers a wonderfully nuanced and insightful narrative of aphasia and life. Ackerman’s detailed accounts of how—and how successfully—she created a rich environment to support Paul’s ongoing recovery can also serve as an inspiration for clinicians, clients, and their families to work out creative ecologies for learning through life after brain damage.

Footnotes

[a] http://www.dianeackerman.com

[b] All quotations with page numbers are from Ackerman’s One Hundred Names for Love.1

[c] See videos of Diane Ackerman and Paul West describing their experiences with his aphasia at: http://www.dianeackerman.com/one-hundred-names-for-love-by-diane-ackerman

[d] This approach stands in stark contrast both to cultural myths that see writing as a solitary activity and to clinical models that equate writing primarily with orthographic coding processes. It is important to recognize that assisted writing, such as described here, is actually quite typical. Indeed, it is well documented that many authors have complex supports for their writing including talking through ideas with collaborators, using others to take dictation, and engaging in collaborative writing/editing across multiple drafts. See for example, discussions by Karen Burke LeFevre3 and Vera John-Steiner.4

[e] See p. 311 for the full list of 100 pet names that gave the book its title. See also a video of Diane Ackerman reading from and reflecting on this section of the book, at: http://www.dianeackerman.com/one-hundred-names-for-love-by-diane-ackerman

References

- Ackerman D. One Hundred Names for Love: A Stroke, a Marriage, and the Language of Healing. New York: Norton; 2011.

- Ackerman D. An Alchemy of Mind: The Marvel and Mystery of the Brain. New York: Scribner; 2004.

- LeFevre KB. Invention as a Social Act. Carbondale, IL: Southern University Press; 1987.

- John-Steiner V. Creative Collaboration. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2000.

- West P. The Shadow Factory. Santa Fe, NM: Lumen; 2008.

- Luria AR. The Man with a Shattered World: The History of a Brain Wound. New York: Basic Books; 1972.

- Sacks O. The Man who Mistook his Wife for a Hat. New York: Harper & Row; 1970.

- Geertz C. The Interpretation of Cultures: Selected Essays. New York: Basic Books; 1973.

- Hengst JA, Devanga S, Mosier H. Thin vs. thick description: analyzing representations of people and their life worlds in the literature of Communication Sciences and Disorders (CSD). Am J Speech Lang Pathol. 2015;24:S838-S853.

- Hengst JA, Duff MC. Clinicians as communication partners: developing a mediated discourse elicitation protocol. Topics Lang Disord. 2007;27(1):37-49.

- Hengst JA, Duff MC, Dettmer A. Rethinking repetition in therapy: repeated engagement as the social ground of learning. Aphasiology. 2010;24(6-8):887-901.

Member since 2019 | JM14274

Member since 2019 | JM14274

NO COMMENT