Eye Spy for Physical Therapy Graduate Education: A Collaboration with the Gibbes Museum of Art

By Cindy B. Dodds, Elise Detterbeck, Debby Passo, Sydney Hammond, Rebecca Rudsill, and Steven Phillips

“The best teachers are those that show you where to look, but don’t tell you what to see.”

Alexandra K. Trenfor

The attainment of expert knowledge and skills is essential to producing competent healthcare practitioners; however, competencies require expertise not only in knowledge and skill (Bloom’s Cognitive and Psychomotor domains), but also the ability to effectively observe and communicate (Bloom’s Affective domain).1,2 Although affective (emotional, feeling) skills are considered important, academic faculty often neglect to address students’ affective qualities due to their subjective and personal nature. Instructional methods designed to develop students’ affective skills can be challenging, but are worthwhile and should address the components of the domain: receiving (eg, listening, observing), responding (eg, participating, discussing), valuing (eg, inclusion, diversity, implicit behavior), organization (eg, balanced decision making, responsibility for one’s behavior), and characterization (eg, having values that guide behavior, self-reliance, cooperation, empathy).3

One innovative pedagogical approach targeting affective domain components is that of providing collaborative instruction led by health professions faculty and museum educators within an art museum setting using Visual Thinking Strategies (VTS).4 Philip Yenawine,4 a VTS expert, supports that these strategies provide students with the opportunity to think, develop, and share observations and ideas, to listen well, and to develop mutual understanding—all of which are relevant to students studying within healthcare fields.

Because museums are not typical healthcare educational settings and art-based experiences allow for different perspective-taking (taking another person’s viewpoint into account) and interpretations, they provide a non-judgmental and less authoritative setting for learning than hospitals and clinics. This approach allows healthcare students and faculty to safely contemplate more affective inquiries in an environment that allows bi-directional learning side-by-side rather than in the more typical top-down, hierarchical approach.5 VTS implementation into healthcare education has been successfully demonstrated among several investigators. Katz and Khoshbin6 report gains in diagnostic skills and teambuilding for medical students and interprofessional teams after their participation in VTS training. In addition, nurse educators have documented improvements in students’ clinical observation skills7 as well as communications and attitudes8 following practices using VTS training. Although not specific to VTS, Klappa and colleagues9 used the creation of art and a corresponding art show by doctor of physical therapy students to prompt new methods of communicating, thinking, and promoting the field of physical therapy.

In an effort to identify pedagogy that enriches instructional designs for development of a student’s affective domain, the Medical University of South Carolina’s (MUSC) College of Health Professions and Humanities committee funded a pilot opportunity for eight physical therapy students to study within the Gibbes Museum of Art located in Charleston, South Carolina with a physical therapy faculty member and professional museum educators. The purpose of this article is to describe curriculum development and program activities as well as discuss preliminary outcomes and feasibility associated with this pilot instructional opportunity involving humanities and physical therapy education.

Study Design

As part of the 2015 Harvard Macy Institute’s Program for Educators in Health Professions supported by the Gold Foundation, the corresponding author previously participated in a remarkable “Reflections in the Museum” session with trained museum educators as well as international and interprofessional colleagues at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. The incorporation of VTS was an integral part of “Reflections in the Museum,” with three questions applied to the observation of a work of art serving as the overarching VTS structure: (1) What is going on in this piece?; (2) What do you see that makes you say that?; and (3) What more can we find?

Other key elements of the experience worth noting include the facts that:

- The professionally trained museum educators were essential to the process, masterfully guiding the instruction and reflection.

- The neutral, non-healthcare environment provided a platform for the safe exchange of personal thoughts, feelings, and interpretations.

- Participants’ sharing supported the uptake of interprofessional and interpersonal insight, views, and perspective-taking.10

Believing that this process would have a positive impact on the affective domains of healthcare graduate students, the corresponding author contacted the Curator of Education at the Gibbes Museum of Art, a local museum within walking distance of the MUSC campus, to discuss a possible collaboration based on the concepts applied in “Reflections in a Museum.” Following several introductory meetings involving two museum educators, the pilot program, “Eye Spy for Physical Therapy Graduate Education: A Collaboration with the Gibbes Museum of Art,” was created. The course syllabus was developed and shared with doctorate of physical therapy students from the first- and second-year classes.

Course Development

Syllabus Course Description

Humanities in Healthcare and Healthcare Education are used to foster patient and healthcare worker self-care and resiliency (ie, playing a musical instrument or painting for enjoyment and pleasure), but also to improve the observation and communication skills necessary for delivering compassionate, collaborative care. As such, the MUSC College of Health Professions and Humanities committee is funding a pilot opportunity for eight physical therapy students to visit the Gibbes Museum of Art and study with faculty and professionally trained museum educators.

Objectives and Outcomes

Following participation in three visual-art learning sessions, the student will:

Objective 1: Demonstrate improved observation skills using vision, hearing, touching, smelling, and tasting (as appropriate). Student observation skills will be measured using a pre- and post-test.

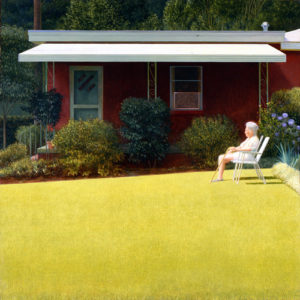

Outcome 1: The observation skills pre- and post-test will use a painting entitled 502 Lucerne Street by Edward Rice. (Figure 1). During this 10-minute observational activity, students will answer the following questions:

- What do you see first?

- Can you list 5 other things you see?

- What does it mean? How does it make you feel?

- What are you going to do about it?

This pre- and post-test had been successfully used by members of the Gibbes Museum of Art practicing VTS with primary and secondary public-school children.

Figure 1:502 Lucerne Street, ca.1983-86, by Edward Rice; oil on canvas; Gibbes Museum of Art; Charleston, SC

Objective 2: Appreciate and respect the uniqueness of each visual art interpretation by peers as measured by qualitative methods during focus groups.

Outcome 2: A focus group, made up of participating students, two museum educators, the Curator of Education from the Gibbes Museum of Art, and a physical therapy faculty member, will address qualitative aspects of the course experience. It will occur over lunch 10 days following completion of the course. The questions posed by the physical therapy faculty member during the focus group will be:

- Do you think the experience will help you be a better healthcare provider? If so, how? If not, why?

- What were the best parts of this opportunity?

- Since this is a pilot opportunity, additional questions related to improving the experience will be asked. They will include:

What are any suggestions you have for improving this project and/or its experience?

How many sessions would be ideal?

Should this project: (1) be mandatory or elective? (2) be interprofessional? (3) involve students lacking compassion, or demonstrating difficulty with interpersonal or interprofessional communication?

Should this opportunity involve patients? If so, at the museum? Hospital as in-patient? Clinic as out-patient? - Knowing what you know now, would you again participate in the program?

- Would you recommend the opportunity to others?

Objective 3: Students will demonstrate greater verbal communication confidence as measured by video recordings for verbal participation and clarity.

Outcome 3: In order to capture verbal communications for analysis, the large group activities will be audio-and video recorded using a Cannon HD camera (VIXIA HF R600) on a stationary tripod.

Review and Consent

Institutional Review Board approval was not required for this instructional experience, due to its classification as a quality improvement project. Participating students did sign consent forms for their participation, and for the recording of images and sound during the instructional experience at the Gibbes Museum of Art and focus group at MUSC.

Course Participants

The pilot course had faculty and funding support from the College of Health Professions Division of Physical Therapy at MUSC; therefore, physical therapy students were approached for participation. Eight students volunteered to participate in this learning opportunity. Three were in the first year of the physical therapy curriculum and five were in the second year. One white male and seven white females participated.

Course Implementation

Under the direction of two museum educators at the Gibbes Museum of Art, eight physical therapy students and one physical therapy faculty member participated in a weekly two-hour session over three consecutive weeks. This opportunity was offered in the evening after students’ coursework for the day was completed, and on an evening when the museum remained open to the public.

- As part of the first session, students completed the pre-test in a museum classroom before advancing into the actual museum.

- Each week of the course included two small group activities and one large group activity led by museum educators. Each week, art selections and lesson plans for these group activities were developed by the museum educators and reviewed with the MUSC faculty member (corresponding author). Although VTS was the framework for inquiry during the sessions, museum educators and the MUSC faculty member wove aspects of healthcare and/or patient-focused discussion into the group learning activities.

- During the small group activities, following the principles of VTS, the museum educators facilitated students’ discussions involving different paintings.

- Large group activities, also involving specifically-chosen pieces of art, were structured differently from small group discussion and are described in the Table.

- After the third and final session, students completed the post-test based on the painting entitled 502 Lucerne Street, the same painting that was observed during the pre-test. Evidence and findings concerning the intersection of VTS, healthcare education, and visual art was provided to students at the conclusion of the third and final session.

Results and Discussion

Qualitative, rather than quantitative, findings from our pilot course better informed the results and discussion.

Observation Skills

Pre- and post-test observation results using the painting 502 Lucerne Street revealed that students may have developed a slight improvement in their attention to detail, as their written responses were more descriptive. For example, on the pre-test, one student reported seeing “elderly woman sitting with cane, purple flowers, basking in sun, stairway with rail to door” and on post-test noted “line of the green grass at angle to house, light green/yellow/white short grass behind chair, shadow of chair, yellow flowers at corner of lawn.” Another student’s pre-test response was “hydrangeas, window unit, grass!, healthy shrubs, cane, second chair” with the post-test remarks including “green!, chairs (one empty), diagonals (yard, windows, cane), well-groomed landscape, home.”

Although post-test descriptions were to some extent more thorough, the pilot’s pre- and post-test question that asked students to “list 5 things other things you see” in the painting, failed to effectively capture substantive observational changes. In the future, we will follow Naghshineh’s lead,11 in which specific healthcare curricular content will be linked to carefully selected paintings in order to extract healthcare significance. Naghshineh and colleagues11 used Claude Monet’s La Japanese (Camille Money in Japanese Costume) to discuss a neurological examination of a patient, specifically related to balance. Future courses will attempt to narrow the observational focus of students to be more pointed and relevant to healthcare.

During small and large group activities, the students’ ability to extract meaningful information from visual detail was noticed. Students, museum educators, and faculty were surprised and pleased with the students’ capacity to extract details and construct creative interpretations. Take, for example, the section of the course where students created cinquain (simple, five-line) poems (see Table, Week 2); working with this format required students to be selective and organize information in a meaningful way. This type of summary and reorganization of information is known to be essential in the development of critical thinking and analysis skills.12 The process requires students to consider and synthesize details in order to create a meaningful whole.

Lastly, comparing the first to the third and final session, students noted they were better able to focus on the “whole picture” rather than isolated features within a painting. They compared this to identifying a patient as a “whole” person rather than defining the individual by their diagnoses or impairments. Recognizing and translating human-centeredness into patient care is an essential step in the process of becoming compassionate healthcare providers.

Communication, Reflection and Perspective-Taking

The use of a stationary video camera to capture and analyze verbal and non-verbal communications did not effectively work because the museum setting was a much more fluid environment than expected. Throughout small and large group activities, students, museum educators, and faculty frequently moved about a piece of art within the museum environment. As this project proceeds in the future, videographers will be employed to better capture the students’ verbal and non-verbal communications as they interact with each other, museum educators, and faculty in this rich environment. Not only will these video recordings make communication outcomes more measurable; the review of them by the students themselves may provide valuable opportunities for self-reflection and self-appraisal.

During the focus-group discussions at the end of the course, all the students said the experience may not have improved their cognitive and psychomotor abilities as healthcare providers, but it did enhance reflection. Although there is no hard evidence that reflective learning practices directly impact patient care,13 reflective practices do enhance learning.14 Using reflective practices (affective domain) in conjunction with knowledge (cognitive domain) and skill instruction (psychomotor domain) promotes better overall learning, which should increase the likelihood of improving human-centered healthcare practices. Although evidence does not yet exist within the literature to support this theory, the results of our pilot course may provide direction for a future longitudinal study that will examine the impact of affective training in students on direct patient care.

The museum setting provided a safe space for the students to express, discuss, and learn “what others thought,” therefore generating perspective-taking. This process encouraged reflection and thoughtfulness rather than judgment and reactivity—an extremely important skill to master prior to integration into stressful clinical settings. For example, one student shared that her family had often commented about her “indifferent” facial expressions, but she ignored their feedback because she felt she wasn’t indifferent toward other people. Following the museum experience, where multiple perspectives were shared and discussed, she began to reflect on her family’s feedback and considered how her demeanor might be affecting others. Recognition of this behavior will allow her to modify her facial expressions as needed during encounters with patients and colleagues, which should in turn enhance her professional performance.

Creativity

Activation of the students’ creative processes was a strength of this pilot project. Students enjoyed the opportunity to create within this novel learning environment. As healthcare students, much of their curriculum involves the uptake of important science, math, and technological knowledge and related psychomotor skills, often interfering with opportunities for creative expression. Using creative instructional strategies as well as being inspired by paintings and sculptures, the students enjoyed expressing meaning through art, such as in writing poems and interpreting sculptures in terms of capturing their movements. For example, in a popular exercise, students created cinquain poems (simple poems in a five-line format) using the process found in the Table, Week 2. See Figure 2 for their creative works.

Suggestions by Students, Museum Educators, and Faculty

Feedback from students, museum educators, and faculty was sought to improve the pilot course.

- Students strongly recommended that the course be an interprofessional and collaborative experience with healthcare students from different programs (eg, nursing, dentistry, basic science, medicine). Museum educators and faculty fully concurred.

- Students unanimously agreed that more sessions would be advisable, suggesting sessions every other week over a semester, which would equate to approximately seven sessions. Faculty and museum educators agreed; Naghshineh and colleagues11 documented greater improvement in the observation skills of medical students following eight or more art observation sessions. The group agreed that future Eye Spy courses would extend for eight sessions over a semester.

- Students, museum educators, and faculty unanimously agreed that patients and caregivers should be part of the Eye Spy experience. Patient and caregiver inclusion would begin in the museum setting and transition over time, and trials, into the hospital room and outpatient settings.

- Students supported the elective nature of the course. They expected that mandatory student participation might contaminate the experience for them; however, student discussions did encourage an Eye Spy model that would support participation of any peers who lack self-reflection. Such students could be referred to the course and encouraged by their peers or faculty to participate in it. Student mentors from previous Eye Spy courses could be influential in the recruitment and experiential process.

- All the students who participated in the pilot course said they would participate again, and would recommend the opportunity to other students.

- The students appreciated not being introduced to the evidence supporting the Eye Spy program until the last session. They believed that the introduction of evidence prior to the experience would have hampered the creative process they so enjoyed.

- The MUSC faculty and the Gibbes Museum faculty acknowledged the need to refine the topic toward more of a healthcare perspective, through the choice of images and questions designed to narrow the focus of observations made by students during the pre- and post-tests.

Feasibility

As it is with most newly-launched pilot educational projects, examining the feasibility of an instructional strategy is wise, especially when introducing a creative instructional method into a more traditional healthcare curricular environment and collaborating with a new community partner. While information shared in this article provides descriptions for curriculum development, program activities, and preliminary outcomes in hopes of encouraging replication, it was just as important to answer preliminary questions concerning feasibility.15 In the case of this project, the answer to the initial feasibility question of “can it work?”15 was “yes.”

Establishing a collaborative partnership between an academic institution and a local community-based museum was indeed possible. Learning and recognizing the importance of involving museum educators in the process was essential—more than expected—because of their specific VTS training and expertise. In answer to the question “does it work?”15 preliminary results indicated that students’ reflection, perspective-taking, and creativity were engaged. The question of “will it work?”15 will be left to future studies testing hypotheses related to the impact of humanities instruction on student learning as well as on healthcare students’ ability to deliver human-centered care once they are practicing healthcare providers.

Future Directions

With limited evidence concerning the incorporation of VTS and, more broadly, humanities education, into physical therapy and interprofessional healthcare education, this project served as an initial attempt to provide a particular course description and explore the feasibility of its implementation. Although VTS and other humanities strategies have demonstrated improvements in diagnostic ability, team building, communication, and observation skills,6-8 longitudinal studies are needed to examine whether such instructional strategies actually translate into students becoming more human-centered healthcare providers.

This pilot project establishes that VTS-enhanced reflection and perspective-taking in physical therapy education is effective; however, it remains to be seen whether similar work can enhance the affective domain qualities of healthcare students. If it can, then the next question to pose to researchers is, will improvements in affective domain qualities lead to improved human-centered clinical care by providers who participated in learning opportunities involving VTS and humanities? By systematically carrying out studies to answer these questions, longitudinal evidence can be compiled. With funding in place and using quantitative and qualitative methods, these authors are currently examining the observation skills and the verbal and nonverbal language skills of an interprofessional group of healthcare graduate students currently participating with museum educators, healthcare educators, and patients in eight sessions of visual exploration across museum and hospital settings.

Limitations

It is likely that selection bias impacted the results obtained from this pilot session. All the participating students were interested in art and had previous experience studying art and touring museums; therefore, they may have already possessed practiced communication and observation skills prior to their course participation. They also may have been more naturally comfortable observing and discussing personal reflections regarding the artwork. Additionally, involvement of students and a faculty member from only the physical therapy program may have limited the possible range of observations, communication, and creativity. Including interprofessional colleagues may enhance responsiveness in future studies.

Conclusion

Implementation of Eye Spy for Physical Therapy Graduate Education: A Collaboration with the Gibbes Museum of Art, a pilot project, was successful. Participating students demonstrated slight improvements in observation skills, and the ability to consider other perspectives. They also began to better explore the concept of human-centered care. Students also valued the opportunity to access and practice their creativity. Suggestions from students, museum educators, and faculty will enhance future implementation of an interprofessional Eye Spy for Graduate Education: A Collaboration with the Gibbes Museum of Art, ultimately supporting longitudinal work to identify a link between humanities-focused content within healthcare education, and human-centered care.

Acknowledgements

The MUSC students and faculty of Eye Spy for Physical Therapy Graduate Education: A Collaboration with the Gibbes Museum of Art would like to thank the Gibbes Museum of Art, Rebecca Sailor, Elise Detterbeck, and Debbie Passo for their invaluable support. Thank you also to the MUSC Humanities Committee and the College of Health Professions, Division of Physical Therapy, whose funding supported this pilot work. Thank you to Lisa Kerr, PhD, at the MUSC Center for Academic Excellence for editorial support. This project would not have been possible without the support of those mentioned here, and we are grateful.

References

1.Bloom BS, Engelhart MD, Furst EJ, Hill WH, Krathwohl DR. Taxonomy of Educational Objectives: The Classification of Educational Goals. Handbook I: Cognitive Domain. New York, NY: David McKay Company; 1956.

2.Krathwohl DR, Bloom BS, Masia BB. Taxonomy of Educational Objectives: The Classification of Educational Goals. Handbook II: Affective Domain. New York, NY: David McKay Company; 1964.

3.Wilson LO. The Second Principle. 2017; http://thesecondprinciple.com/instructional-design/threedomainsoflearning/, 2017. Accessed March 21, 2017.

4.Yenawine P. Visual Thinking Strategies: Using Art to Deepen Learning Across School Disciplines. Boston, MA: Harvard Education Press; 2013.

5.Miller A, Grohe M, Khoshbin S, Katz JT. From the galleries to the clinic: applying art museum lessons to patient care. J Med Humanit. 2013;34(4):433-438.

6.Katz JT, Khoshbin S. Can visual arts training improve physician performance? Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc. 2014;125:331-341; discussion 341-332.

7.Pellico LH, Friedlaender L, Fennie KP. Looking is not seeing: using art to improve observational skills. J Nurs Educ. 2009;48(11):648-653.

8.Klugman CM, Peel J, Beckmann-Mendez D. Art rounds: teaching interprofessional students visual thinking strategies at one school. Acad Med. 2011;86(10):1266-1271.

9.Klappa SG, Alles YB, Klappa SP. DPT program stages an art show using art to develop a heart for the profession of physical therapy. J Human Rehabil. 2017. https://scholarblogs.emory.edu/journalofhumanitiesinrehabilitation/2017/05/02/dpt-program-stages-an-art-show-using-art-to-develop-a-heart-for-the-profession-of-physical-therapy//. Accessed April 1, 2018.

10.Gaufberg E, Williams R. Reflection in a museum setting: the personal responses tour. J Grad Med Educ. 2011;December:546-549.

11.Naghshineh S, Hafler JP, Miller AR, et al. Formal art observation training improves medical students’ visual diagnostic skills. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(7):991-997.

12.Fiorella L, Mayer RE. Learning as a Generative Activity: Eight Learning Strategies That Promote Understanding. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2015.

13.Mamede S, Schmidt HG. The structure of reflective practice in medicine. Med Educ. 2004;38(12):1302-1308.

14.Driessen E, van Tartwijk J, Dornan T. The self critical doctor: helping students become more reflective. BMJ. 2008;336(7648):827-830.

15.Bowen DJ, Kreuter M, Spring B, et al. How we design feasibility studies. Am J Prev Med. 2009;36(5):452-457.

Appendix

| Activity | |

|---|---|

| Week 1 | Upside/Down Poem Have students look at a piece of art for 30 seconds. Ask them to come up with one word (no more than 7-8 letters) that explains the piece of art. Then write the word vertically on board or paper. Then for each letter have students identify other descriptive words that start with or end with, or contain the letter. Do not repeat a word or use similar words. Complete this process 3 or more times to create a word bank for a poem. Example: W welcoming wise wired R royal romantic riveting I industrial virtual vindictive T Titanic complete twisted E energetic pretend trite Poems can be created by reading a column up or down or by reading columns diagonally or randomly. |

| Week 2 | Improv Theatre 1. Students stand around a sculpture. 2. Each student in turn acts out a gesture that reflects some part of the sculpture and shares it with the group. 3. The group then interprets the meaning of the gesture. 4. After each student’s sharing and group response, the group links each of the gestures into a fluid movement that embodies their collective response. Cinquain Poems, developed from the following process: Line a: General 1-word topic related to painting. Line b: 2 vivid adjectives describing the topic from the painting. Line c: 3 ing-action verbs describing the topic from the painting. Line d: 4-word phrase that describes the feeling associated with the topic from the painting. Line e: 1 specific word that explains line a. |

| Week 3 | Personal Response Tour Each of the below listed tasks are placed on slips of paper. Each student blindly selects a slip of paper with one of the following tasks. Students then explore the museum to identify a piece of art that speaks to the task. Once each student has completed the task, they discuss findings with the larger group. Tasks • Focus on a memorable patient of the past year, and find a work of art that person would find meaningful or powerful. • Find a work of art from a culture or religious tradition other than your own, and identify something you find beautiful about the work. • Find a work of art that reminds you of something from your past; think about the connections. • Find an image of a person and imagine what they would have been like at another stage in their life. • Find an image of a person with whom you find it challenging to empathize. What seems to be blocking your connection? • Find a work of art that speaks to either a JOY or a STRUGGLE you have experienced during training. |

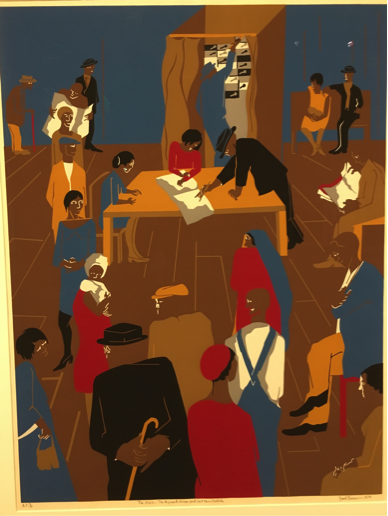

Figure 2. Cinquain Poems, based on paintings at the Gibbes Museum of Art, Charleston, SC

Work: The 1920’s…the Migrants Arrive and Cast Their Ballots, 1974, by Jacob Lawrence; silk screen on paper; © 2015 The Jacob and Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence Foundation, Seattle / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Poem by: Anonymous

Voters

Patient Eager

Queuing, Reading, Choosing

This is our first time

Citizens

Work: Olympic Games, 1971, by Jacob Lawrence; screenprint on paper; © 2015 The Jacob and Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence Foundation, Seattle / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Poem By: Steven Phillips DPT Class of 2019

Boundaries

Reliant Restricted

Straining Resisting Pushing

A snapshot suspended in

air, yet grounded

Limitations

Work: Family from the Hiroshima series, 1983, by Jacob Lawrence; silk screen on paper; © 2015 The Jacob and Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence Foundation, Seattle / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Poem by: Catherine Stone DPT Class of 2018

Pain

Deep, Broken

Crumbling, Crashing, Screaming

We are trying to be together, a family,

but we are torn & nothing can be the

Same

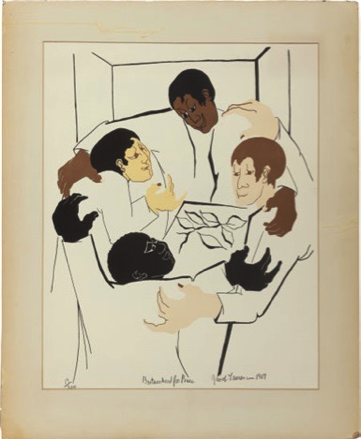

Work: Brotherhood for Peace, 1967, by Jacob Lawrence; lithograph on paper; © 2015 The Jacob and Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence Foundation, Seattle / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Poem by: Lauren Vann, DPT Class of 2018

Brotherhood

Peaceful, Non-judgmental

Sharing, Helping, Hoping

Why can’t it always be like this?

One

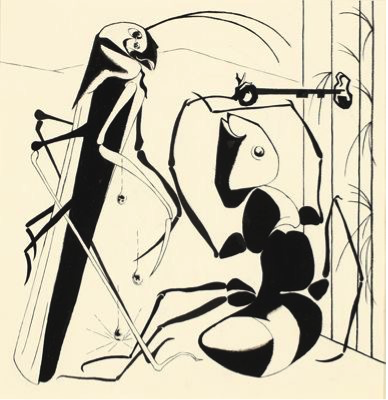

Work: The Ant & The Grasshopper, 1997, by Jacob Lawrence; woodcut on paper; © 2015 The Jacob and Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence Foundation, Seattle / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Poem by: Rebecca Rudsill, DPT Class of 2019

Caricature

Backlit, Angular

Playacting, Exaggerating, Squawking

Why are these little bugs so angry?

Shadows

Work: Carpenters, 1977, by Jacob Lawrence; offset lithograph on paper; © 2015 The Jacob and Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence Foundation, Seattle / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Poem by: Katherine Hefner, DPT Class of 2018

Wood

Sturdy, Smooth

Building, Holding, Supporting

The saw cuts it

Tree

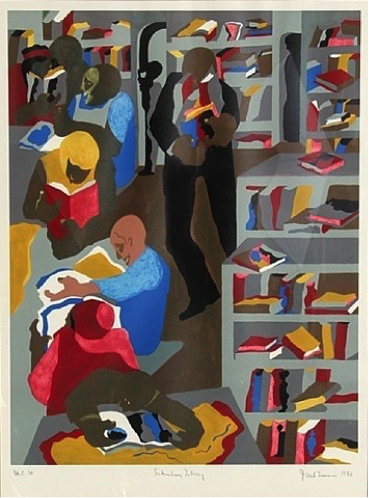

Work: Schomburg Library, 1987, by Jacob Lawrence; Lithograph on paper; © 2015 The Jacob and Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence Foundation, Seattle / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Poem by: Anonymous

Book

Red, Hand

Reading, Sharing, Gathering

He is telling stories to his friends

Knowledge

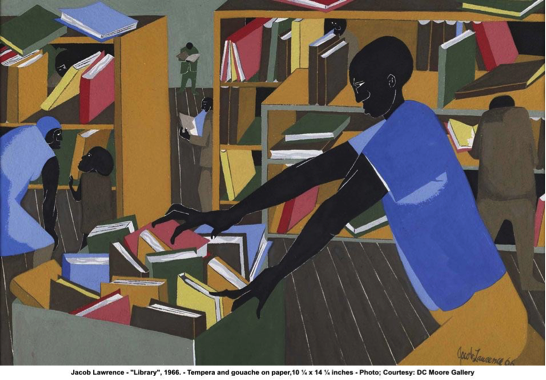

Work: The Library, 1978, by Jacob Lawrence; silkscreen on paper; © 2015 The Jacob and Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence Foundation, Seattle / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Poem by: Meghan Bowman, DPT Class of 2018

Seeker

Curious, Safe

Exploring, Feeling, Searching

He is eager to gain knowledge of

the unknown

Adventurer

Work: Aspiration, 1988, by Jacob Lawrence; lithograph on paper; © 2015 The Jacob and Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence Foundation, Seattle / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Poem by: Josie Horne, DPT Class of 2018

Home

Silent, Still

Sitting, Reading, Sharing

The townspeople bustle about

Togetherness

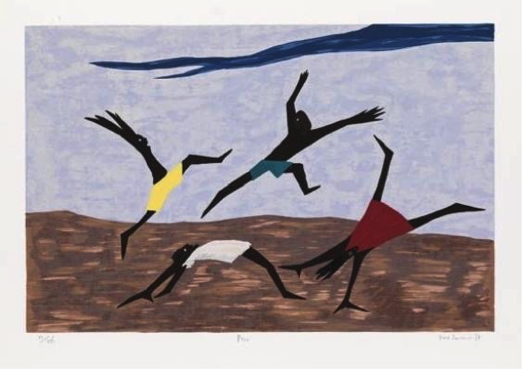

Work: Play, 1999, by Jacob Lawrence; silk screen on paper; © 2015 The Jacob and Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence Foundation, Seattle / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York Poem

by: Sydney Hammond, DPT Class of 2019

Children

Colorful, Carefree

Moving, Interactive, Laughing

Flow of playful joy

Youth

Poem by: Anonymous

Play

Colorful, Creative

Leaping, Dancing, Cartwheeling

Watch the Dance of Joy Among

friends

Smile

Member since 2019 | JM14274

Member since 2019 | JM14274

NO COMMENT