The Fragility of Life: Through Service I Live

By Corey Nolte, PT, DPT

Cancer, the emperor of all maladies.1 A six-letter word that sends chills down your spine. Individuals diagnosed with or battling cancer, according to Susan Sontag, have crossed into the “kingdom of the sick.”2 Like me, those who care for these patients are reminded our sojourn in the kingdom of the well is temporary.2 Persons who are newly diagnosed, currently battling, or have advanced stages of cancer foresee a future of suffering, of hopelessness, and of confronting mortality. In many instances, as their cancer progresses, they become frail and fragile, as their energy reserves and body systems shut down. As these reserves fade away, many seek services like palliative and hospice care. Those who care for these patients can appreciate how fragile and unpredictable life is.

Sick and Tired

As of 2016, an estimated 15.5 million Americans with a history of cancer were alive in the United States. By 2026, that number is predicted to skyrocket to 20.3 million individuals.3 Interestingly, persons aged 65 years and older are projected to account for 70% of all cancer diagnoses.4 Frailty is intimately linked to aging. It is known that older adults constitute a significant proportion of people diagnosed with cancer, increasing their predisposition to illness.5 This may make managing frail patients with cancer several times a year commonplace for practitioners in oncology.6

Debilitating physical side effects of adjuvant therapy such as cachexia, graft versus host disease, and mucositis can lead to failure to thrive. Psychological side-effects like depression, stress, and loss of control contribute to diminished quality of life.7 Specifically, the burden of cancer-related fatigue (CFR) is correlated with high levels of disability.8 CRF is a never-ending cycle, lasting years after treatment, causing tiredness, mood disorders, and sleep disturbances, making mundane medical treatments and simple self-care tasks seem untolerable.9,10

Evidence suggests that physical therapists are equipped to treat patients with advanced stages of cancer, and exercise can positively impact well-being.11,12 But what happens when the patient is tired of the fight against cancer and is ready to throw in the towel? During my residency year, my narrow-minded understanding of the resiliency of the will to live was expanded.

A Personal Case Study

With a soft knock on the door, I walked into the patient’s room, introducing myself as the patient’s physical therapist. I was greeted by a gloomy environment giving off an aura of “Not now, come back later.” The lights were off, shades down, a table tray of food untouched, and the patient covered in sheets not acknowledging my presence. Nevertheless, there I stood, an over-enthusiastic new graduate eager to shine light in this patient’s life through movement. When I saw her, the word “emaciated” came to mind, but did not surprise me due to her previous diagnosis of Acute Myeloblastic Leukemia (AML), treated by autologous stem-cell transplant (ASCM) a year earlier. She met all the checkboxes4 for frailty: low level of physical activity at home, self-reported exhaustion with showering while seated, and unintentional weight loss. To make matters worse, she was given the worst news: her leukemia had relapsed.

After spending increased time to motivate, encourage, and educate the patient on the role of physical therapy, the patient reluctantly agreed to allow me to assist her with a stand pivot transfer from bed to the bedside commode. I remember thinking to myself that the first session was a disaster. Did it do more harm than good? The patient’s sheer exhaustion, let alone the moans, groans, and guarded positioning due to pain, questioned if what I was doing was truly therapeutic.

With each subsequent physical therapy session, she became more withdrawn. The frequency of canceled sessions increased. Eventually the words “I want to give up. I just want to die,” came out of her mouth. It became abundantly clear there was much more at play here than the patient’s activity limitations. Her life’s energy was dwindling.

For me, this was a first as a clinician. I had never heard anyone say those words, let alone with such certainty and veracity. Frankly, it was a shock to my system. I naively assumed that when patients have cancer or relapse, they do everything in their power to fight, and absolutely never give up. After all, I am not a stranger to cancer. My mother has battled cancer off and on since the early 1990’s, has endured multiple abdominal surgeries including a hysterectomy, and has received experimental chemotherapy and radiation. I vividly remember seeing my mother’s hair fall out as she threw up due to the side effects of her treatment, but never heard her say those dreaded words. I responded to the patient the best I could by asking her a series of suicide safety assessment questions and reported what the patient had told me to her nurse. I remember leaving the patient’s room with a feeling of uncertainty and my initial gut reaction was to reach out to my mentor for guidance.

While updating my mentor on the patient’s case, I felt as if I was at a standstill. I remember thinking, “How do you reach someone who does not have the will to live?” I felt as if I exhausted all my resources. I tried to utilize family as motivation, scheduled a wheelchair transport outside for the patient to get a breath of fresh air and Vitamin D, and even made a referral to the recreational therapist. All to no avail. After an enlightening conversation with my mentor about being “present in the moment,” I decided to go out on a limb of faith and pursue supererogatory action.

At the beginning of the next session, I sat at eye level with the patient, to try to get a sense of where she was both mentally and physically. I saw her crucifix—the same golden crucifix I noticed last session. I asked the patient if she was spiritual, and with her consent, we held hands in prayer, heads bowed. As our eyes met at the end of the intercession, I saw we had both teared up.

What the patient and I experienced in this moment was the product of a social interactive process taking situational awareness and emotion into consideration. Her vulnerability and my personal experience as a caregiver to my mother created an unspoken understanding between us. This situation led me to make a referral to a Chaplain, a step in which the patient was very much in favor. Ultimately, this patient decided treatment was medically futile. After a goal-of-care meeting with the medical team and her family, her code status was changed to DNAR/AND with elected inpatient hospice. She quietly passed away a week later.

Looking back at this experience, I realized the lack of moral sensitivity that had distorted my initial reactions and plan of care. I was trying to motivate someone who had already come to terms with her mortality. I should have been validating her self-determination, not trying to change it. An end-of-life conversation can be one of the most challenging to have in the patient/therapist relationship. The old adage “Life is not always black and white, it’s a million shades of grey” comes to mind. As clinicians we may possess the facts and information about the patient’s medical condition. We might also be the most efficient in our evaluations and treatment sessions. However, the challenge that arises is to have the sensibility to be in unison with the patient during a unique circumstance. By practicing active listening and being more in sync with the patient’s goals, I am certain I can help prevent future miscommunications.

Reflection for Action

As humans, we avoid the topic of death. I am guilty of pushing it off, because it is uncomfortable to come to terms with the fact that we are all terminal. No one wants to think about death as we falsely believe a whole life remains in front of us, and especially if it means considering leaving this world behind. However, there is something to be said for being comfortable with your own mortality and your beliefs about end of life. It can create a greater appreciation and respect for patient autonomy by bringing awareness to a topic seldom confronted in the field of physical therapy, and can even act as a catalyst for physical therapists to support patient wishes for nothing more than comfort measures at the end of life.

Since this therapeutic engagement, I have considered whether or not I wish to have ordinary versus extraordinary means of medical care if faced with a similar circumstance. Additionally, I have even pursued steps to establish an advanced directive at what might be considered a young age. I encourage other healthcare providers that experience health crises on a regular basis in the workplace to do the same.

Ultimately, life is delicate, chaotic, and beautiful—but that makes the human condition precarious. Not only has this shared human experience shined a light for me on the fragility of life, but it has molded my professional identity. I realize that, through serving others, I find purpose as a clinician by fulfilling my moral obligation as a human being especially when the traditional role of physical therapy is challenged. By demonstrating kindness, and carefully supporting end-of-life wishes, we can help to unburden patient angst and give direction to our own moral compass.

References

- Mukherjee S. The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of Cancer. New York, NY: Scribner; 2010.

- Sontag S. Illness at a Metaphor. New York, NY: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux; 1978: 3.

- Rowland JH, Mollica M, Kent EE. Abeloff’s Clinical Oncology. Sixth Ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier. 2020:733.

- Hogan DB, Maxwell CJ, Afilalo J. A scoping review of frailty and acute care in middle-aged and older individuals with recommendations for future research. Can Geriatr J. 2017;20(1):22-37.

- Ribeiro, AR, Howlett SE, Fernandes. Frailty-a promising concept to evaluate disease vulnerability. Mech Ageing Dev. 2020;187:1-8.

- Balducci L, Stanta G. Cancer in the frail patient: a coming epidemic. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2020;14(1):235-248.

- Courneya KS, Friedenreich CM. Physical exercise and quality of life following cancer diagnosis: a literature review. Ann Behav Med. 1999;21(2):171-179.

- Jones JM, Olson K, Catton P, et al. Cancer-related fatigue and associated disability in post-treatment cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv. 2016;10:51-61.

- Mustain KM, Alfano CM, Heckler C, et al. Comparison of pharmaceutical, psychological and exercise treatments for cancer-related fatigue a meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol. 2017:1-8.

- Johnson, JA, Garland SN, Carlson LE, et al. Bright light therapy improves cancer related fatigue in cancer survivors: a randomized controlled trial. J Cancer Surviv. 2018;12:206-215

- Baldwin A, Wilson C. Best practices for public policies for palliative care physical therapy: a critical review of the literature. Rehabil Oncol. 2018:106-116.

- Loh KP, Kleckner IR, Lin P, et al. Effects of a home-based exercise program on anxiety and mood disturbances in older adults with cancer receiving chemotherapy. JAGS. 2019;67(5):1005-1011.

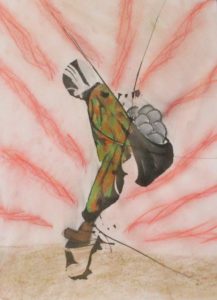

Figure 1. “Burdens We Carry” (ink and chalk pastel)

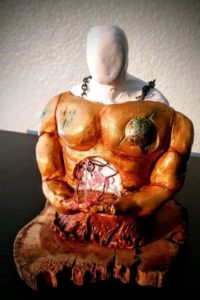

Figure 1. “Burdens We Carry” (ink and chalk pastel) Figure 2. “Removing My Armor” (air-dry clay and mixed media)

Figure 2. “Removing My Armor” (air-dry clay and mixed media) Figure 3. “Construction Anew” (Ink and oil pastel)

Figure 3. “Construction Anew” (Ink and oil pastel)

Member since 2019 | JM14274

Member since 2019 | JM14274

NO COMMENT