Art Informing Interdisciplinary Care for a Veteran Recovering from Traumatic Brain Injury: A Case Study

By Gayla Elliott, MA, A.T.R.;1,2 Christopher M. Filley,1,4,5,6 MD; Ashley V. McCann, PT, DPT;1,4 Hilary A. Diefenbach, MA, CCC-SLP, CBIS;1,2 Andrea Lucie, Ph.D.;1,2 Mason E. Heibel, EOD, CPT, fmr; Judith Vanderryn, Ph.D.1,2

Marcus Institute for Brain Health,1; Departments of Family Medicine,2 Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation,3 Neurology,4 and Psychiatry,5 and Behavioral Neurology Section,6 Anschutz Medical Campus, University of Colorado School of Medicine, Aurora, Colorado

Abstract

United States Military Veterans with traumatic brain injury (TBI) typically have other medical conditions such as post-traumatic stress, insomnia, headache, chronic pain, and moral injury. Interdisciplinary care that holistically addresses TBI and comorbidities is a preferred approach to care. One challenge of interdisciplinary care is effective communication between the patient and providers, as well as among the providers themselves. Discipline-specific jargon, while relevant and effective for diagnosis and documentation, potentially creates confusion in communication with patients and colleagues.

The importance of addressing injuries from a holistic perspective is highlighted in this case study, encouraging rehabilitation clinicians to consider incorporating Art Therapy into interdisciplinary care. By expanding the therapeutic lens and developing a broader, deeper, and more humanistic understanding of symptomatology, interdisciplinary care is enhanced.

The Marcus Institute for Brain Health (MIBH) at the University of Colorado provides interdisciplinary diagnosis and treatment of war Veterans with TBI and comorbidities. The Intensive Outpatient Program at MIBH includes neurology, psychotherapy, physical therapy, speech and language pathology, integrative medicine, and Art Therapy, among other medical disciplines.

In this case, a Veteran’s art served as a visual means of communication, powerfully and immediately expressing mental, physical, emotional and spiritual injuries. The Veteran’s art increased his self-awareness while informing the clinical team of his ongoing experience. Art guided and informed clinical care as providers addressed problems such as psychological impairments, laryngeal dysfunction, postural deviation, and manifestations of unprocessed grief and trauma.

This case study shows how a trauma-informed, creative, interdisciplinary approach can improve communications in clinically assessing and treating Veterans suffering from the complexities of military service-related TBI and psychological trauma. The study highlights implementing Art Therapy to aid a Veteran in processing trauma, while also empowering him to use his visual art to communicate to his interdisciplinary therapists in a unique and powerful manner.

Introduction

Interdisciplinary care (IDC) is crucial to treating Veterans with traumatic brain Injury (TBI) and post-traumatic stress (PTS), because the etiology of symptoms may be impossible to identify and apportion.1,2 A diverse healthcare team addressing TBI and PTS from multiple perspectives increases the likelihood of improved functioning and thriving as a “whole person.”3,4 Interdisciplinary care requires healthcare professionals to address physical, psychological, and spiritual needs. The patient, and when possible the patient’s family, are members of the team.

Art Therapy has been successfully incorporated in military healthcare settings across the U.S. and elsewhere to address physical and psychological injuries of war.5-11 The goal of this paper is to highlight the role of Art Therapy as a component of interdisciplinary care for Veterans with TBI and PTS.

Several studies exploring Art Therapy within interdisciplinary care for TBI rehabilitation have emerged from active-duty military healthcare settings.5,9-12 The National Endowment for the Arts: Creative Forces website is an excellent resource to review research with “key clinical findings indicating that the creative arts therapies can enable recovery from traumatic experiences.”13 This study furthers these previously-published findings by examining the impact of Art Therapy on a Veteran’s interdisciplinary care in an outpatient rehabilitation setting.

The Marcus Institute for Brain Health (MIBH) addresses the complex needs of Veterans with TBI and related psychological disorders. This uniquely-designed program allows for more in-depth behavioral health and integrative approaches than traditional rehabilitation programs.

The MIBH provides interdisciplinary evaluations and treatment using the innovative Integrated Practice Unit (IPU) model, which seeks to “improve patient-centeredness,”14 and allows Veteran to access informed and highly personalized care. The IPU helps avoid silos of specialty care, and organizes healthcare according to patient needs. “In an IPU, a dedicated team…of both clinical and nonclinical personnel provides the full care cycle for the patient’s condition.”15 Art Therapy plays an essential role at MIBH. Therefore, the aims of this case study are to demonstrate how:

- Art Therapy provided a Veteran the opportunity to creatively express himself and expand his participation on the care team by non-verbally communicating his experience of biological, psychological, social, and spiritual injuries.

- Art created by the Veteran informed the care he received from an art therapist, clinical psychologist, integrative therapist, physical therapist, and speech-language pathologist.

Case Description

The individual described in this case was a 34-year old Caucasian Veteran of the United States Army (co-author “MH”). He served as a US Army Explosive Ordnance Disposal Technician and was exposed to numerous blasts during his military service. MH had one combat deployment to Afghanistan in 2014. During that deployment, he sustained his worst head injury, with loss of consciousness from close-range exposure to an explosive device. MH was medically separated from military service with 100% service-connected disability. His health conditions included PTS, TBI, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and tinnitus. He reported depression and anxiety, problems with memory and concentration, chronic fatigue, headache, impairments in coordination and balance, dyspnea on exertion, throat discomfort, photophobia, and orthopedic injuries.

The interdisciplinary team diagnosed multiple mild TBIs, with ongoing neurological sequelae. Post-traumatic stress, including moral injury, was diagnosed by the clinical psychologist. Impairments of visual motion sensitivity, cervical proprioception and reduced efficiency of postural control in eyes-closed conditions with aggravation of symptoms (dizziness and nausea) were identified by the physical therapist. Exercise limitations and throat tension and discomfort, previously diagnosed as paradoxical vocal fold movement, were recognized by his speech-language pathologist. The integrative therapist’s evaluation identified moral injury and unresolved grief from a spiritual perspective. Art Therapy recognized anxiety and the need for trauma processing, increased self-awareness, and emotional regulation.

The Use of Art Therapy to Elicit a Veteran Voice

At the MIBH, Art Therapy targets the treatment goals of reducing anxiety, expressing feelings, gaining insight and self-awareness, improving emotional regulation, and enhancing neuroplasticity.16 After the initial Art Therapy session, specific goals are identified and projects are tailored to each Veteran’s injuries and experiences. Although Art Therapy is a mental health profession, this case describes how MH’s art expressed psycho/social/spiritual themes, and also his lived experience of physical conditions. Data collection for this case study involved photographing MH’s artwork and collecting statements he wrote to describe his art-making process.

Week 1

At the MIBH, Art Therapy begins with a projective technique in which each Veteran creates an abstract ink design, identifies an image embedded in the design, and completes the picture with colored media.17 The art therapist guides the Veteran in verbally exploring this imagery to find meaning. Artwork emerging from this project contains themes often tied to trauma, which informs and helps refine treatment goals. Figure 1 displays MH’s initial inkblot drawing.

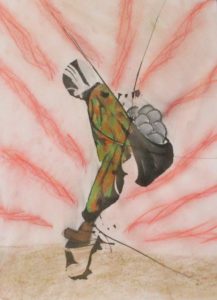

Figure 1. “Burdens We Carry” (ink and chalk pastel)

Figure 1. “Burdens We Carry” (ink and chalk pastel)

Narrative from MH: A nondescript Soldier carries stones, burdens from life and war. Uncomfortable and unstable, the Soldier struggles to gain positive footing but is met with resistance from the weight of the load. Hands are one with the satchel; this burden has become a part of the Soldier. Pain and uncertainty accompany every step; progress is slow to nonexistent. (MH)

Interpretation from the IDC team: Figure 1 illustrated immobilization, both physically and emotionally. MH identified the satchel of stones as a metaphor for guilt, regret, and moral injury that had burdened him for years following repeated traumatic losses. This picture was effective in describing MH’s perception of psycho-spiritual challenges and physical imbalance and restriction.

Week 2

Generally, by the second week of the MIBH Intensive Outpatient Program (IOP), patients are fully engaged in therapy, and artworks shift toward illustrating themes of change. In week two, MH created a small clay sculpture (Fig. 2), based on imagery elicited from eye movement desensitization and reprocessing18 sessions with the psychologist. At this point, MH began requesting additional time in the Art Therapy studio to process changes he was experiencing as a result of care.

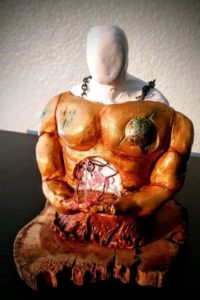

Figure 2. “Removing My Armor” (air-dry clay and mixed media)

Figure 2. “Removing My Armor” (air-dry clay and mixed media)

Narrative from MH: A nondescript warrior removes worn and battle-damaged armor. The warrior has carried this armor for lifetimes and finds it fused to his flesh. Removing this armor is painful and scary but necessary for growth. Like a beetle molting its exoskeleton for growth, so must this warrior put aside his armor. Nature reaches up to assist the warrior, with all things returning to the Earth to be cleansed and eventually renewed. (MH)

Interpretation from the IDC team: Metaphorically “wearing armor” is a common phenomenon of the physical manifestation of stress from traumatic events.19 A guided visualization of releasing symbolic body armor during a psychotherapy session was made concrete in this sculpture. Symbolizing this process with tangible materials provided MH the opportunity to sustain focus on dismantling his armor: a meditative process to visualize change.

Week 3

In the third week, final therapeutic interventions take place. Veterans and IDC clinicians establish closure and follow-up care. In choosing a final art project, MH came “full circle,” returning to the ink-blot technique (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. “Construction Anew” (Ink and oil pastel)

Figure 3. “Construction Anew” (Ink and oil pastel)

Narrative from MH: Form in chaos. Momentum and energy are moving towards rebirth and growth. A new world is born from removing the barriers and confinement built by self-destruction. Construction is not yet in a finalized form but has purpose and uses new tools. (MH)

Interpretation from the IDC team: MH identified a black raven (center), sunset, water, and mountains in this inkblot. Themes from nature have been identified in Art Therapy research as symbols of healing.5 From a gestalt perspective, and in contrast to the immobilized soldier in Figure 1, this picture resembled a human figure striding forward with fluid movement.

Although MH created other artworks, those displayed here mark important stages in his healing process: (1) identifying problems; (2) visualizing change; and (3) utilizing new skills to empower himself. Reflecting on his Art Therapy experience, MH wrote:

Art Therapy is a remarkable tool that allowed me to access my subconscious and conscious minds. It was an outlet for emotions and self-realizations to be expressed when words failed. Art was the most efficient way for me to show my pain, my barriers, and my progress. Pain is such a specific internal state, difficult to express so others truly understand. I found that using art allowed me [to] express my pain in a universal language. My team was able to observe issues I presented in my art I would never have been able to express in words. Some of these issues were outside my conscious awareness until I processed them through art and received feedback. My burdens and armor had become a part of me to the point where I was unable to separate them from myself. Art Therapy allowed me to access uncomfortable areas in an organic and comfortable manner and maximized my time at MIBH. It is a tool I still use and find comforting and stabilizing in times of chaos and uncertainty.

Veteran Artwork Influencing Clinical Care

Several times a week, the IDC team met to discuss and refine MH’s care. His artwork and comments were presented by the art therapist during rounds. The art therapist identified symbols in the artwork relevant to interdisciplinary therapeutic goals. Each clinician shared observations allowing for the integration of multiple perspectives. This created an improved, holistic clinical understanding and assisted in designing humanistic, person-centered, integrated care. MH’s artwork depicted themes that overlapped disciplines. For instance, artworks describing psychological and spiritual burdens were simultaneously symbolic of physical posturing, pain, and restriction. The collective effect of multiple therapists communicating and treating interwoven symptoms was articulated by MH: “The IOP felt like one continuous session with different components, each offering a unique avenue for healing.” This holistic approach and response may provide a case-level example of successfully utilizing mind/body interventions.20

Each work of art created by MH provided direct communication with the care team, who used their discipline-specific interpretation to direct treatment strategies. Figure 1 illustrated psycho-spiritual challenges related to PTS and moral injury. In psychotherapy, MH explored his belief that carrying emotional burdens was his responsibility, yet these burdens were immobilizing. Integrative techniques based on Eastern medicine conceptualized the spiritual injuries and energetic blockages from trauma recognized in Figure 1. MH needed permission and effective tools to release the guilt and fear he carried. Art Therapy, psychotherapy, and integrative therapy all utilized metaphors embedded in Figure 1 to understand MH’s experience of PTS and moral injury.

The physical stance illustrated in Figure 1 mirrored symptoms identified by the physical therapist and the speech-language pathologist. The physical therapist observed forward head posture and guarded positioning, matching MH’s physical presentation with postural-balance instability. Patterns of muscle tension evident in the drawing mirrored MH’s physical presentation in voice therapy as well. Behavioral habits of breath-holding, over-exertion in physical activity, and musculoskeletal chest and neck tension were addressed by the speech-language pathologist, increasing MH’s awareness of stress and tension in daily life. Diaphragmatic breathing was encouraged across all disciplines for a variety of physical, emotional, and spiritual benefits.

The eye movement desensitization and reprocessing provided by MH’s psychologist helped him recognize the metaphorical armor he had donned for psychological protection, which manifested as tension-holding physical restriction in his upper body. In week two, MH explored the concept of slowly removing this “armor,” with visualization techniques. Art Therapy provided him an opportunity to symbolize removing armor. A detailed, nuanced description of this process appears in the Veteran’s clay sculpture (Fig. 2). Simultaneously, “removing armor” provided an opportunity in integrative therapy to explore vulnerability, a necessary step toward healing spiritual wounds. A practice consisting of mantras and yoga, focusing on the solar plexus energetic center, was initiated by the integrative therapist. According to Eastern medicine, the solar plexus is located in the abdomen, where armor was being dismantled in the sculpture.

The speech-language pathologist also focused on the abdomen, promoting diaphragmatic breathing and relaxation, and demonstrating that body tension and strain had limited MH’s physical performance and vocal function.21 From a physical therapy perspective, this sculpture signified a shift in posture and movement, with the figure appearing strong, centered, and physically grounded.

In week three, MH continued to struggle with self-acceptance and worthiness. Psychotherapy incorporated visual and kinesthetic metaphors to develop internal and external resources. Integrative therapies provided introspective work, visualizing the release of spiritual burdens, reducing the need for protective defenses. These interventions helped MH embrace the freedom expressed in Figure 3.

From the physical therapist’s viewpoint, a gestalt view of Figure 3 resembled a figure running. This interpretation was congruent with MH becoming more physically active and striding forward in life, using new tools to progress further in the future. The speech-language pathologist observed that Figure 3 expressed releasing internalized strain. The heavy figure portrayed in Figure 2 transformed to embody weightlessness, fluidity, and ease in Figure 3. The team observed a transformation in MH’s art, from protective and imbalanced in week one, to open, free, and forward-moving in body, mind, and spirit in week three.

An intriguing element of this case is the rich clinical discussion that resulted from the art therapist inviting all clinical providers to recognize visual symbols relevant to diverse and overlapping therapeutic goals. Additionally, art provided a language and a tool for synthesizing the internal and external changes MH was experiencing in treatment. Art Therapy was satisfying and beneficial for MH, and offered a visual, universal language to communicate his unique experience of injuries and healing to his IDC team.

Conclusions

This case study demonstrates how Art Therapy was an essential element of an IDC team treating a Veteran with TBI and PTS. The study examines how the Veteran used Art Therapy to assist in recovery from traumatic experiences and how his artwork informed the IDC team. Art Therapy is a promising component of TBI rehabilitation that merits further study and application. A limitation of this study is that MH’s experience may not generalize to other injured Veterans receiving Art Therapy. Further research is needed to explore the effectiveness of Art Therapy for TBI and PTS, and to examine specific outcomes of Art Therapy in patients receiving IDC.

References

- Vasterling JJ, Jacob SN, Rasmusson A. traumatic brain injury and posttraumatic stress disorder: conceptual, diagnostic, and therapeutic considerations in the context of co-occurrence. J Neuropsych Clin Neurosci. 2018;30(2):91-100.

- Vanderploeg RD, Belanger HG, Horner RD, et al. Health outcomes associated with military deployment: mild traumatic brain injury, blast, trauma, and combat associations in the Florida National Guard. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2012;93(11):1887-1895.

- Department of Veterans Affairs. VHA handbook 1172.01: Polytrauma system of care. Washington DVHA. 2013.

- Strasser DC UJ, Smits SJ. The interdisciplinary team and polytrauma rehabilitation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;179-181.

- Berberian M, Walker MS, Kaimal G. ‘Master my demons’: art therapy montage paintings by active-duty military service members with traumatic brain injury and post-traumatic stress. Med Human 2019;45(4):353-360.

- Lobban J, Murphy D. Understanding the role art therapy can take in treating Veterans with chronic post-traumatic stress disorder. Arts Psychother. 2019;62:37-44.

- Howie P. Art Therapy With Military Populations: History, Innovation, and Applications. Taylor & Francis; 2017.

- Mandić-Gajić G, Špirić Ž. Posttraumatic stress disorder and art group therapy: self-expression of traumatic inner world of war Veterans. Vojnosanitetski pregled. 2016;73(8):757-763.

- Kaimal G. Evaluation of long- and short-term art therapy interventions in an integrative care setting for military service members with post-traumatic stress and traumatic brain injury. Arts Psychother. 2019;28-36.

- Walker MS. Art therapy for PTSD and TBI: A senior active duty military service member’s therapeutic journey. Arts Psychother. 2016;49(6):10-18.

- Maltz B. A case analysis of service-member trauma processing related to art therapy within a military-intensive outpatient program. J Clin Psychol. 2020;76(9):1575-1590.

- Walker MS. Outcomes of Art Therapy Treatment for Military Service Members with Traumatic Brain Injury and Post-traumatic Stress at the National Intrepid Center of Excellence. 2019;63(4):18-30.

- National Endowment for the Arts: Creative Forces National Resource Center. https://www.creativeforcesnrc.arts.gov/

- van Harten WH. Turning teams and pathways into integrated practice units: appearance characteristics and added value. Internat J Care Coord. 2018;21(4):113–116.

- Porter ME, Lee TH. “The Strategy That Will Fix Health Care.” Harv Bus Rev. 2013;October:50-70.

- King JL. Practical Applications of Neuroscience-Informed. Art Ther. 2019;36(3):149-156.

- Virshup E. Right Brain People in a Left Brain World. Guild of Tutors Press; 1978.

- Russell MC, Figley CR. Treating Traumatic Stress Injuries In Military Personnel: An EMDR Practitioner’s Guide. Routledge; 2013.

- Burnett HJ. An exploratory study on psychological body armor. Crisis, Stress, Hum Resil. 2019;1(2).

- Van der Kolk BA. The Body Keeps The Score: Brain, Mind, And Body In The Healing Of Trauma. Penguin Books; 2015.

- Shaffer M, Litts JK, Nauman E, Haines J. Speech-language pathology as a primary treatment for exercise-induced laryngeal obstruction. Immunol Allergy Clin. 2018;38(2):293-302.

Member since 2019 | JM14274

Member since 2019 | JM14274

NO COMMENT