Introduction

Since the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA, 1990) there has been increased interest in promoting a better understanding and acceptance of persons with disabilities, as well as improving the societal discrimination they face. The Disability Rights Movement developed primarily in the last quarter of the 20th century with considerable growth in advocacy efforts over the past three decades (eg, see Lives Worth Living). Of primary importance, the ADA prohibits discrimination and ensures equal opportunity for persons with disabilities in: employment; state and local government programs and services; access to places of public accommodation such as business, transportation, and non-profit service providers; and telecommunications. Although the ADA has provided greater opportunities and access for persons with disabilities, in order for them to attain complete inclusion into society, it is essential to change the negative attitudes and misperceptions regarding them commonly held by the general public—as well as by many rehabilitation professionals.

The manner in which individuals with disabilities were perceived, treated, and integrated into societies throughout history is complex and related to multiple issues involving economic, scientific, and religious factors.1 In the past, individuals with disabilities were frequently viewed as objects to be ridiculed and for the most part they have been perceived as a burden to others and considered to be of limited value to society.2,3 This was due in large part to the limited understanding of human anatomy and physiology, as well as the lack of methods to treat disease and injuries, minimize impairments, or develop assistive devices (eg, prosthetic devices, assistive technologies, environmental accommodations). As such, they were often socially ostracized and driven to live on the margins of society. In contrast, there have also been various cultures and religious sects throughout history that have tended to care for and be empathetic toward individuals with disabilities.

Imagery From Ancient Times to the Present Day

Ancient writings and images reveal a wide variety of messages about how individuals with disabilities were treated and perceived in early historical times, including the portrayal of disability as a source of punishment in the Code of Hammurabi (ca. 1780 BCE), as predictors of good or bad events in The Omen Series Summa Izbu (ca. 1300 BCE), as individuals capable of community leadership in Homeric writings (The Iliad, 750 BCE), or even as a mark of beneficence in ancient Egypt.2,4 However, few know that Aristotle proposed a law to prevent parents from raising deformed children,5 that Spartan laws obliged parents to abandon deformed children,6 or that Cicero claimed that the body determined the ‘shape’ of the soul.7 Even numerous biblical passages demonstrate how individuals with various physical disabilities (eg, leprosy and paralysis) were perceived and treated negatively.2,8 In fact, numerous laws/policies throughout history legalized or encouraged discrimination against individuals with disabilities and such negative representations further reinforced public perception of disability as ‘abnormal,’ along with the social division between the disabled and nondisabled.9 These negative perceptions of disability generally persisted until the second half of the 20th century when advances in medicine and innovative treatments/technologies allowed for the approach to disabilities to be improved.

Training in Disability Issues Across Rehabilitation Professions

With the development of the profession of physical medicine and rehabilitation following World War II, society began to view more consistently individuals with disabilities as worthy of treatment, and to assist them in recovering as fully as possible and returning to productive, independent lives.10 Since then, rehabilitation disciplines have developed training guidelines to improve the health and functioning of individuals with disabilities (Table 1). In general, these professional organizations call for training based on medical models that emphasize knowledge and skills, often leading to the treatment of individuals as ‘disorders’ (eg, a spinal cord injury, a traumatic brain injury, a stroke) or ‘impairments’ (eg, forgetfulness, irritability, spasticity), rather than individuals with disabilities. As such, rehabilitation ‘success’ could be over-simplistically evaluated in terms of improvements in range of motion, memory scores, or increased psychological traits, without consideration of the need for full inclusion of individuals with disabilities into society. Because of these factors, it has been concluded that rehabilitation professionals “are often negative about disability, seeing inability before ability and frustrated by the lack of a prospect of cure and ill-informed about simple accommodations.”11(p462)

_______________

Table 1: Rehabilitation Discipline Training Guidelines

American Board of Internal Medicine (2013). Internal medicine/physical medicine and rehab policies. Accessed online on 7/20/2020 at: http://www.abim.org/certification/policies/combinedim/comrehab.aspx

Accreditation Content for Occupational Therapy Education (2018). Standards of practice for occupational therapy. Accessed online on 7/20/2020 at: https://acoteonline.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/2018-ACOTE-Standards.pdf

American Physical Therapy Association (2018). Standards of practice for physical therapy. Accessed online on 7/20/20 at: http://www.apta.org/uploadedFiles/APTAorg/AboutUs/Policies/HOD/Practice/standards.pdf.

American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. (2020). Scope of practice in speech

language pathology [Scope of Practice]. Accessed online on 7/20/20 at: https://www.asha.org/certification/2020-slp-certification-standards/.

American Psychological Association Rehabilitation Psychology Division (2012). Guidelines for postdoctoral training in rehabilitation psychology. Accessed online on 7/20/20 at: https://www.apa.org/pubs/journals/features/rep-a0030774.pdf.

American Therapeutic Recreation Association Standards of Practice. Accessed online on 7/20/20 at: https://www.atra-online.com/page/SOP.

_______________

More recently, there has been increased recognition of the need for training in the ability to understand the personal experiences of persons with disabilities and the societal biases experienced by these individuals (sometimes referred to as training in issues of attitude). It is relatively easy to teach knowledge (eg, facts, diagnostic criteria) and skills (eg, procedures, tests, discipline-specific therapies), as these are generally fact-based and able to be memorized. However, it is much more difficult to mold individual and societal attitudes (ie, conscious and unconscious biases and beliefs) about disabilities. Changing attitudes and beliefs, however, is central to improving the lives of people with disabilities given that prejudicial and exclusionary social practices are believed to be greater barriers to social participation than specific mental, physical, or sensory impairments.12 It is important for healthcare professionals to examine their own beliefs about disability and awareness of how persons with disabilities are perceived, portrayed, and treated today, and particularly for those rehabilitation professionals who work with these populations on a daily basis.

Rehabilitation Psychology Training Guidelines: An Example

Although all rehabilitation training guidelines generally focus on the medical model, initial post-doctoral training guidelines for rehabilitation psychology provide an example of training methods to address issues of attitude. This specifically involves the need to be educated about the manner by which disability is a socially-constructed phenomenon, as well as the manner by which our own biases affect our treatment, interactions with, and expectations for, individuals with disabilities. For example, one of the most notable rehabilitation psychology guidelines calls for training in “cognitive, affective, and societal sources of handicapped myths about disability and ways to counteract them.”13 This suggestion is truly unique among the various rehabilitation disciplines in that it acknowledges the significant role that societal expectations and misperceptions have in the manner by which individuals with disabilities are treated. Although this suggestion is noteworthy, there are no specific methods to suggest how to train rehabilitation professionals regarding the societal perceptions that impact persons with disabilities. This article suggests that studying images of disability in art history is an important and impactful method for teaching rehabilitation professionals about the experiences and biases experienced by those patients they serve.

Art as a Means to Better Understand the Experience of Disability

Human beings have made art to communicate and connect with each other since prehistoric times. Art has the powerful ability to help viewers relate to the individuals depicted in the image on a human, empathetic level, which, in turn enhances the goal of understanding and acceptance on a new level. Artists have used various mediums (eg, paintings, poetry, narratives, sculpture, film, etc.) to express emotional turmoil, tragedy, social isolation, and psychological disturbance as a means to relate and share personal experiences. The medical, legal, and social zeitgeist of an era is often reflected by the artwork created of that time. Alternatively, societal perceptions have long been influenced by how individuals with disability are represented to the public visually and politically. There are few primary sources from ancient and medieval times regarding people with disabilities,3 and as a result, researchers have relied on the arts to determine the social context of disability at various times throughout history. In fact, a historian of disability states that, “Studying the representation of disability in literature and art is an important and relatively unexplored research frontier in disability studies.”14(p 54)

The arts have been used in rehabilitation for people with disabilities primarily through recreational therapies in which individuals engage in the visual arts, music, dance, and expressive writing to adjust to their disabilities. However, a review of artistic representations of disability throughout history also offers an excellent method by which to improve the training of rehabilitation professionals. There is increased recognition that studying the humanities helps health professionals gain a better understanding of the human side of chronic disabilities.

People with disabilities are depicted throughout art history, and these images provide a context for the manner by which they were perceived at that time (eg, worthy of derision or sympathy, objects of ridicule, deserving of divine punishment, etc.). For example, prior to the advent of the printing press, when much of the population was illiterate, paintings were often used to tell stories, depict historical events, and provided examples of how people were treated.3 As such, many individuals learned social expectations for how to treat the disabled by viewing paintings in churches or watching plays during community festivals. It is from these works of art that we can understand the culture of the times and become sensitized to the relevant social issues of the day as they pertain to disability. By comparing past and current art forms (eg, paintings, drawing, and sculptures from the past to movies, films, and literature from the present) it is possible to better understand how societal perceptions have a major influence on the way individuals with disabilities are treated. Subsequently, training methods can be developed to counter “social myths of disabilities” (see APA Division 22 training guidelines), and educate rehabilitation professionals to become better providers for individuals with disabilities.

PART 1: The Representation of Physical Disability in Art History

Throughout history, individuals with physical disabilities have primarily been perceived and represented as ’misfits, fools, oddities, and marvels,’ present in the world for purposes of entertainment, ridicule, and experimentation.2 This relates in part to the lack of understanding of the causes of physical disability, as well as the lack of resources, knowledge, or will to develop accommodations during various historical times. As such, individuals with disabilities often had little support from their families and communities and needed to fend for themselves in creative ways; this was generally the case until the last half of the 20th century.

As an example, Greuze’s The Paralytic (1763; Fig. 1) is one of the few depictions of an individual with paralysis, likely due to the fact that the survival rates for such individuals were extremely low.

_______________

Figure 1: Jean-Baptiste Grueze’s The Paralytic, 1763, Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia. (File:Jean-Baptiste Greuze – Filial Piety – WGA10664.jpg – Wikimedia Commons).

_______________

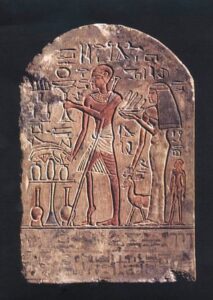

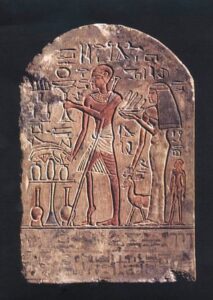

Historically, depictions of physical disability in western civilizations have largely focused on ‘abnormalities’ and the negative manner by which individuals with disabilities were perceived and treated. In fact, a frequently-cited theory from the late 18th century related to physiognomy concluded that the disabled were, “[t]he morally worst, the most deformed.”15 However, it is noteworthy that ancient Egyptian and Greek cultures at various times were generally accepting of individuals with physical disabilities, as illustrated in several of their works of art.4,16,17 For example, a stone carving from approximately 1300 BCE shows a realistic depiction of an Egyptian leader with a withered leg, apparently from polio (Fig. 2). Greek vases show similar representations of dwarves who were valued as assistants within the medical field, and even portrayed as deities.16,17 However, throughout history, such positive depictions of physical disabilities were the exception rather than the rule.

_______________

Figure 2: The Polio Stele, Egypt 18th Dynasty, 1403-1365 B.C., Deutsches Grunes Kreug, Copenhagen, Denmark. (File:Polio Egyptian Stele.jpg – Wikimedia Commons).

_______________

By the Middle Ages, societies began to extend to people with impairments “an acceptance at times awkward, at times brutal, at times compassionate, a kind of indifferent, fatalistic integrations” to people with impairments. 8(p15) However, in general, individuals with disabilities were represented as abnormal, with early portrayals exploiting these abnormalities for amusement. Paintings from this time indicate that individuals with disabilities were viewed in terms of a religious model of disability, in that individuals were believed to be disabled secondary to spiritual transgressions and were thus treated with religious interventions, if they were even treated. Metzler2(p89) reports “anecdotal evidence suggests that there was a very strong feeling that malformed babies indicated sin on the part of their parents.” Spiritual interventions for disabilities were depicted in a painting by di Benvenuto (15th Century), titled St. Catherine of Siena Exorcising a Possessed Woman (Fig. 3), in which individuals with both physical (ie, characters with crutches) and mental illnesses (central figure) caused by demonic possession were treated with religious interventions within a church setting.

_______________

Figure 3: Girolamo di Benvenuto’s St. Catherine of Siena Exorcising a Possessed Woman, c. 1500, Denver Art Museum, Denver, Colorado. (File:’St. Catherine of Siena Exorcising a Possessed Woman’, painting by Girolamo di Benvenuto.jpg – Wikimedia Commons).

_______________

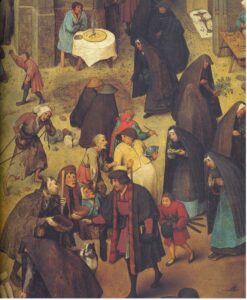

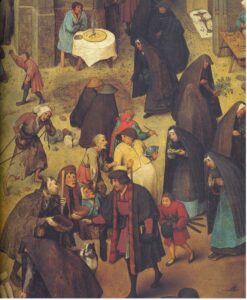

By the 16th century, the Renaissance began to focus on classical forms of beauty, which did not typically include the disabled or deformed. However, art from the northern Renaissance depicted individuals with physical disabilities in a realistic manner, providing insight into the way they were treated and socially perceived at that time. Hieronymous Bosch painted a series of 31 ’cripples’ in 1500, illustrating the various disabling conditions and prosthetic devices used by these individuals.19 Similarly, Bruegel’s The Cripples (1568; Fig. 4) shows individuals with various prosthetics gathered together in a town square. However, historical context indicates that these individuals were forced to wear fox tails attached to their clothes as indicators that they were objects to be ridiculed at community festivals.19,20 Similarly, Bruegel’s Battle Between Carnival and Lent (1559; Fig. 5) shows the relative isolation faced by individuals with disabilities within their communities. Compared to the so-called ‘normal’ citizens participating in either carnival or lent, details from the painting show two groups of individuals with disabilities (ie, ‘cripples’ in middle scene, blind individuals by church entrance) as socially-isolated beggars. These community spectacles are precursors to the freak shows that gained popularity in the mid-16th century and lasted to the mid-20th century, which displayed physically unusual or deformed humans for a source of entertainment21 (Fig. 6). By the 19th century, individuals with impairments were even criminalized through public policy (ie, ’ugly laws’ involving social restrictions placed on those with physical appearances that might offend ’normal’ people)9.

_______________

Figure 4: Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s The Cripples, 1568, Louvre, Paris, France. (File:Pieter Bruegel the Elder – The Cripples – WGA3518.jpg – Wikimedia Commons).

Figure 5: Details from Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s Battle Between Carnival and Lent, 1559, Kunsthistorches Museum, Vienna, Austria. (File:The battle between Carnival and Lent, by Pieter Bruegel (I).jpg – Wikimedia Commons).

Figure 6: Edward J. Kelty, photograph from Madison Square Garden, 1933. Published in Barth M., Siegel AM. Step Right This Way: The Photographs of Edward Kelty (p. 107). New York, NY: Barnes and Noble Books. 2002

_______________

Paintings such as Wyeth’s Christina’s World (1948) provide an example of the social isolation and handicaps faced by many individuals with physical disability even in the middle of the 20th century. This painting appears to show its subject, Christina Olson, admiring a homestead in a windswept field. However, an article in the Journal of Child Neurology22 indicates that Wyeth was portraying a young woman suffering from a progressive neurological disorder that he observed crawling crab-like up to her farmhouse. This knowledge challenges the initial perception of the scene and shifts our position from viewer to Christina’s own perspective. This is the power of studying art history: to guide the viewer by facilitating close looking, deeper contextual understanding, and empathy. An article by J.O. Ballard in JHR is an excellent resource for those who would like to use this painting to increase clinical observation and diagnostic skills regarding disability in health sciences education.23

Even within the past quarter century, controversy surrounding the Franklin D. Roosevelt (FDR) Memorial in Washington, DC illustrates the current difficulties society has in accepting individuals with physical disabilities. FDR’s Splendid Deception24 recounts how the original statue of FDR to be placed at the front of his memorial in Washington, DC was designed to depict him in his wheelchair (he could not walk after contracting polio at age 39). However, when the original sculpture was finished, his cape covered his wheelchair completely, in effect hiding his disability (Fig. 7). A second statue, depicting FDR using his actual wheelchair and placed at the other end of the memorial, was completed only after significant advocacy efforts by disability rights groups. It is important to note that ancient Egyptian society could realistically portray important figures with disabilities with compensatory devices over 3,000 years ago (Fig. 2), but the FDR Memorial planners of the 20th century had problems acknowledging his disability, despite the fact that he was one of the most important and powerful leaders in the world during his lifetime.

_______________

Figure 7: Franklin Delano Roosevelt Memorial, Washington, D.C.(https://www.nps.gov/frde/learn/photosmultimedia/index.htm).

_______________

PART 2: The Representation of Mental and Intellectual Disability in Art History

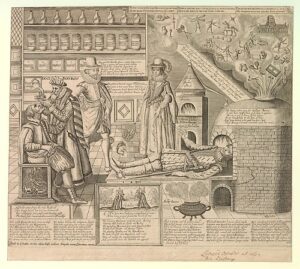

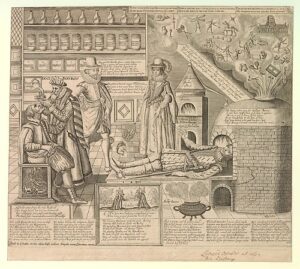

Up until the 19th century, individuals with physiologically-based mental disorders were conceptualized in terms of ‘madness’ primarily related to spiritual disorders that needed to be treated through spiritual interventions (although these beliefs persist in some communities even today). For example, di Benvenuto’s St. Catherine Exorcising a Possessed Woman, shows a demon being exorcised from a woman’s head in the 1300s (Fig. 3). Similarly, Droeschout’s To this Grave Doctor Millions do Resort from the 17th century (Fig. 8) shows a scene in which demons were exorcised from an individual’s head in a fancy contraption (figure on right), as well as from their bowels by the apparent use of an elixir to dispel demons (figure on left).

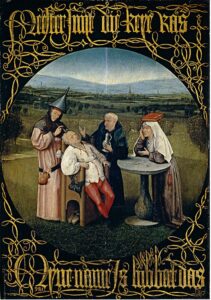

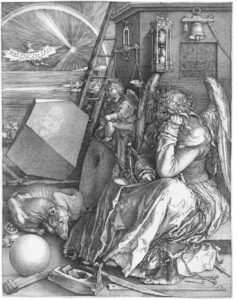

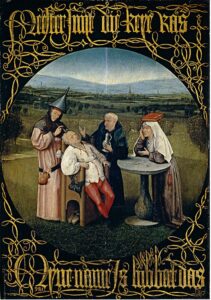

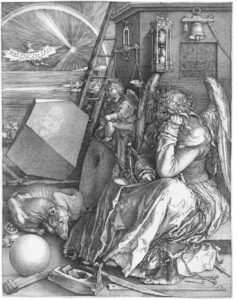

Similarly, a 16th-century painting by Hieronymus Bosch titled The Extraction of the Stone of Madness (Stones of Folly) illustrates the belief at that time that ‘madness’ was due to the presence of a stone within the skull that required extraction in order for the person to be cured (Fig. 9). By 1514, mental illness was believed to be related to an imbalance of the four humors of the body (black bile, yellow bile, blood, phlegm) that led to the four primary human temperaments (melancholic, phlegmatic, choleric, and sanguine)25 as represented in Durer’s Melancholia I (Fig. 10). Frans Hal’s Malle Babbe (1633-1635) illustrates how mental illness (eg, insanity, alcoholism) was conceptualized in northern Europe during the 17th century as being caused by the visitation of the bird of lunacy (Fig. 11).

_______________

Figure 8: Martin Droeschout’s To this Grave Doctors Millions do Resort, c. 1620 – 1630, British Museum, London, England. (File:To this grave doctor millions do resort (BM 1854,1113.154).jpg – Wikimedia Commons).

Figure 9: Hieronymous Bosch’s The Extraction of the Stone of Madness (Stones of Folly), c. 1501 – 1505, Prado, Madrid, Spain. (File:Cutting the Stone (Bosch).jpg – Wikimedia Commons;https://www.museodelprado.es/en/the-collection/art-work/the-extraction-of-the-s

Figure 10: Albrecht Durer’s Melancholia I, 1514, Stadl Museum, Frankfurt, Germany. (File:Dürer Melancholia I.jpg – Wikimedia Commons).

_______________

Art from the 19th century demonstrates how mental (ie, lunacy) and developmental disabilities (ie, ‘idiocy’) started to be conceptualized in a different manner in some cultures, in that such disorders were transformed from being conceptualized as ’madness’ to ’mental illness’ (ie, a medical abnormality)26. For example, in the 1800s, health professionals attempted to distinguish between different types of mental disorders through the identification of unique facial features, similar to the field of physiognomy.

Theodore Gericault painted a series of 10 ’portraits of the insane’ (The Madwoman, 1819-1822; Fig. 12) depicting physical attributes that were thought to be associated with specific psychological disorders—five of the paintings which still exist (Woman Addicted to Gambling, A Child Snatcher, Woman Suffering from Obsessive Envy, Kleptomaniac, Man Suffering from Delusions of Military Command). Although it is difficult to determine how physical features could reveal a ’child snatcher’ or someone with ’military delusions,’ it is noteworthy that mental illnesses were starting to be categorized in terms of specific abnormalities (ie, physical and psychological).

_______________

Figure 11: Frans Hal’s Malle Babbe, 1633-1635, Gemaodegalerie, Berlin, Germany. (File:Frans Hals 021.jpg – Wikimedia Commons).

_______________

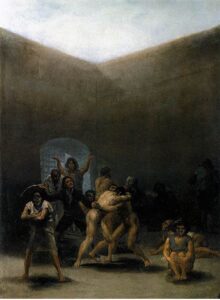

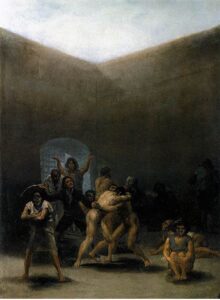

Art from other historical periods also offers insight into the manner by which individuals with mental disabilities were segregated and isolated from their communities. Bosch’s Ship of Fools (1490-1500; Fig. 13) depicts the practice during the 15th century and beyond of rounding up the disabled and unwanted and placing them in a wagon with promises of goods, in order to remove them from society.27 This practice changed in the beginning of the 18th century when individuals with mental and sensory disabilities began to be institutionalized in hospitals or asylums, but without prescribed care or interventions.2,3 Goya illustrated such a lunatic asylum in the 1700s (Fig. 14), but incredibly, this representation differs little from the demeaning conditions depicted in the infamous 1970s documentary about the Willowbrook Mental Institution in New Jersey (Fig. 15). These works of art show how individuals with mental illnesses from the Middle Ages until the 1970s were removed from society and deemed unworthy of treatment, which differs considerably from current societal understanding and increasing acceptance of mental illness.

_______________

Figure 12: Theodore Gericault’s The Madwoman, 1819-1822, Museum of Fine Art, Lyon, France. (File:The mad woman-Theodore Gericault-MBA Lyon B825-IMG 0477.jpg – Wikimedia Commons).

Figure 13: Hieronymous Bosch’s Ship of Fools, 1494 – 1510, Louvre, Paris, France. (https://collections.louvre.fr/en/ark:/53355/cl010062860; https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Jheronimus_Bosch_011.jpg).

Figure 14: Francisco de Goya y Lucientes’s Yard with Madmen, 1794, Meadows Museum, Dallas, Texas. (https://meadowsmuseumdallas.org/collections/pages/objects-1/info/?query=Artist_Maker%3D%2239%22&page=7).

_______________

Although artists throughout history have generally depicted individuals with intellectual disabilities in a negative manner (eg, village idiots, fools), several works of art illustrate how some societies had positive and accepting views of individuals with intellectual disabilities. For example, The Adoration of the Christ Child (circa 1515) offers a powerful message about the acceptance of individuals with developmental disabilities in Northern Europe in the 16th century (Fig. 16). In this painting, medical professionals have suggested that two of the angels surrounding the manger have Down’s syndrome (although the syndrome was not known as such at that time).28,29 This painting likely reflects the longstanding and continued willingness of communities in northern Europe to be inclusive of individuals with intellectual disabilities.

_______________

Figure 15: Willowbrook Asylum. Photograph by William Bronston, 1979, from unpublished book (Public Hostage: Public Ransom – Inside Institutional America; online Archive of California: Finding Aid to the William Bronston Papers, 1961-2008 (cdlib.org)).

Figure 16: School of Jan Joest, The Adoration of the Christ Child, 16th century, Museum of Modern Art, New York, New York. (File:The Adoration of the Christ Child MET DT8852.jpg – Wikimedia Commons).

_______________

PART 3: The Representation of Sensory Disability in Art History

Misperceptions and prevailing attitudes of individuals with sensory disorders date back to the biblical era. In its most dramatic fashion, select scriptures led many to believe that God used deafness and blindness as retribution for sin: “Who gave man his mouth? Who makes him deaf or mute? Who gives him sight or makes him blind? Is it not I, the Lord?” (Exodus 4:11); “…if you do not carefully follow His commands and decrees…all these curses will come upon you and overtake you: the Lord will afflict you with madness, blindness, and confusion of the mind. At midday, you will grope around like a blind man in the dark.” (Deuteronomy 28:15). This demonization of the blind carried on through the Middle Ages and into the Renaissance.

For example, a manuscript from the 14th century, The Romance of Alexander,30 includes illustrations, in the margins, of the daily customs, work, dress, leisure activities, and social norms that existed in Medieval Europe at that time. Of interest, one border illustration shows how individuals with visual impairments were paraded before communities as a form of entertainment at times of festival (Fig. 17), similar to Bruegel’s The Cripples (Fig. 4). Writings from 1425 describe a similar event:

“Note, the last Sunday of the month of August there took place an amusement at the residence called d’Arminac in the Rue Saint Honore, in which four blind people, all armed, each with a stick, were put in a park, and in that location there was a strong pig that they could have if they killed it….and there was a very strange battle, because they gave themselves so many great blows with those sticks that it went worse for them, because when the stronger ones believed that they hit the pig, they hit each other, and if they had really been armed, they would have killed each other. Note, the Saturday evening before the aforementioned Sunday, the said blind people were led through Paris all armed, a large banner in front, where there was a pig portrayed, and in front of them a man playing a bass drum” (as cited in Wheatley26( p1)).

_______________

Figure 17: Illustration from The Romance of Alexander (artist Jehan de Grise), Flanders, Belgium, 1338-1344 (permission from the Bodleian Library).

_______________

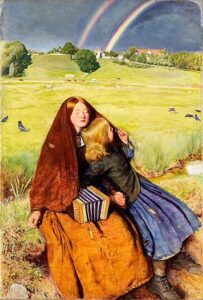

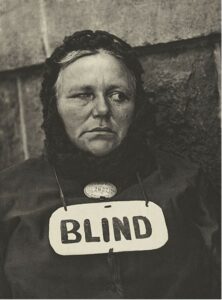

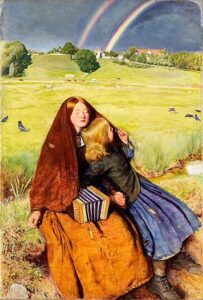

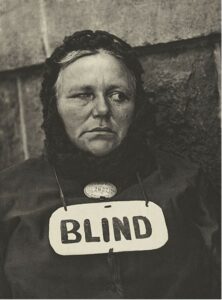

Throughout history, images of the blind beggar have rendered public perception of blind individuals as helpless, useless, and passively dependent. Given the social, vocational, and financial difficulties associated with blindness and marginalization, some blind individuals have succumbed to accepting this role. For example, Millais (1856) portrayed a young blind girl relegated to beg for money by playing her concertina while wearing a sign on her neck displaying the words, “Pity the Blind” (Fig. 18). This was also depicted in a notorious photograph by Strand in 1916 of an impoverished blind woman in New York City, identifying her disability with a sign around her neck saying “Blind,” below the metallic license she needed to obtain to legally beg31 (Fig. 19).

_______________

Figure 18: John Everett Millais’ Blind Girl, 1856, Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery, Birmingham, England. (File:Millais-Blind Girl.jpg – Wikimedia Commons).

Figure 19: Paul Strand’s The Blind Woman, 1916. (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Blind_Woman.jpg).

_______________

Beginning in the 17th century, the perception of individuals with visual disabilities as defective, expendable, and intellectually disabled led to the social control movement of institutionalization for the disabled. In fact, one of the first institutions for disabled individuals was intended for the deaf and the blind, as depicted in Goya’s Yard with Madmen (1794; Fig. 14), which represented scenes of institutions he personally witnessed, and was said to be painted at a time when he feared similar consequences from his own mental illness and deafness. The emotional toll of the blind and deaf, due to marginalization and social stigma, can also be seen in Goya’s Two Old Men (from his Black Painting series; Fig. 20), capturing the darkness and isolation felt during his years plagued with deafness and physical ailment. Similar sentiments are aroused in Degas’ Madame René de Gas (1872/1873; https://www.nga.gov/collection/art-object-page.46599.html), a portrait of his blind sister-in-law’s vacant gaze representing her solitude and isolation, and Picasso’s The Old Guitarist (1903), both depicting tones of sorrow and loneliness. The sorrow and frustration were a product of living in a society that deemed them incapable and blemished, therefore discounting their intact capabilities that could benefit from accommodation.

_______________

Figure 20: Francisco de Goya y Lucentes’ Two Old Men, 1821-1823, Prado, Madrid, Spain. (File:2 alte Männer, um 1821-23.jpg – Wikimedia Commons; https://www.museodelprado.es/en/the-collection/art-work/two-old-men/cde9bf01-7535-4a62-8f73-a22d6a68d9a5?searchid=433a4

______________

During the mid-20th century, Americans with visual impairments described the impact of the beliefs, superstitions, and the social/physical environment as the primary obstacle to the emotional and physical adjustment to their disability, as cited in The War Blind in American Social Structure:

“All too frequently the great tragedy of a blind person’s life is not primarily his blindness, but the reactions of the family and social group toward him as a non-typical member.”32

Today, while ambiguous perceptions of those with sensory impairment still exist, knowledge, technological innovation and accommodations leading to expansive and ready access of support helps afford these individuals education and greater independence. Interpreters are more readily available in health care and educational facilities, along with the transcription of texts to Braille or auditory recordings. With these supports and greater public knowledge, individuals with sensory disabilities have disproved past perceptions of being passive, dependent, helpless, unproductive, or intellectually disadvantaged.

PART 4: Modern Artistic Representations of Disability

Although beyond the scope of this article, it is noteworthy how primary art forms of today (ie, movies, TV) have played a substantial role throughout the 20th and 21st centuries in shaping societal attitudes toward disability. Thus, it is not surprising that the manner by which disability is represented in media art today has also led to greater acceptance of disability. Such realistic and positive representations of disability will continue to teach people who are secure in their beliefs and perceptions of ‘normalcy’ that individuals with disabilities are not subjects to be gawked at or marginalized.

For example, children today are exposed to positive images of disability and representations of characters with disability as leaders, such as those portrayed in the Disney movie Finding Nemo (2003). X-Men is a popular comic magazine that has been made into a series of movies (2000-2019). Of note, Charles Xavier, the leader of this band of individuals with superhuman powers, is confined to a wheelchair. Similarly, the critically acclaimed Murderball (2005) is a documentary film that shows individuals with various forms of paralysis engaging in full-contact rugby in the Paralympic Games in Athens, Greece.

The depiction of mental illness in film has also improved over the past 50 years, with individuals with mental illnesses and sensory disabilities portrayed more realistically and empathetically (One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975); Rain Man (1988); Children of a Lesser God (1986)). Rehabilitation trainees and professionals can watch these and other movies that show the human experience of disability with subsequent discussion at scheduled training opportunities (Table 2). These movies offer opportunities to discuss differences in how individuals with disabilities have been portrayed and treated in the past and currently, and how more positive portrayals can lead to the development of better skills for rehabilitation professionals—and ultimately greater understanding and acceptance of the personal experience of disability.

PART 5: Disability Training Through the Arts

It is suggested that rehabilitation training guidelines promote opportunities for both students and professionals to become aware of the “cognitive, affective, and societal sources of handicapped myths about disability and ways to counteract them” (see APA Division 22 training guidelines) through the study of disability in the visual arts. It is recommended that rehabilitation students and professionals review and discuss the visual arts (and literature) relating to the personal experiences of, and societal perceptions of, disability in existing didactics, grand rounds, and journal clubs. Students and professionals can easily review paintings and articles presented in this article for discussion, and particularly those presented in articles from traditional medical journals and art history journals and textbooks (see References below).

Training directors can also find appropriate topics and offerings on art and disability through many websites and organizations (Appendix 1). Review of the representation of disability in the visual arts can also be discussed based on academic sources that provide contextually-relevant cultural information related to specific eras, as well as autobiographies, novels, and collections of short stories that provide examples that relate the personal experiences of persons with disabilities, the challenges they have faced, and the successes they have had in becoming full members of society (Appendix 2).

Conclusion

In conclusion, this article reflects the benefits and necessity of training in the health humanities (versus medical humanities) for both rehabilitation professionals and those individuals with disabilities they serve. Specifically, the health humanities apply transdisciplinary practices that draw on the humanities, fine arts, and social sciences to bring meaning to human experiences of health and illness, to increase social justice for individuals with illness and disabilities.34 Training in the health humanities can complement training in the medical humanities—which focus on the use of the humanities in service to medicine—to help practitioners learn attributes such as empathy, communication, and compassion.

Member since 2019 | JM14274

Member since 2019 | JM14274

NO COMMENT