This case reflection is presented by an interprofessional rehabilitation team at a private, outpatient rehabilitation practice as an example of a humanistic, person-centered approach to treating pain that emphasizes a biopsychosocial (BPS) framework, including exploration of and reconceptualization of the meaning of pain within a personal and social context. The authors used reflections from multiple stakeholders to attain a deeper understanding of a patient’s pain experience and explored barriers and challenges to the delivery of care within this BPS approach. This reflective learning experience provided an opportunity for professional growth for the members of this interprofessional team with the goal of improving future experiences of healthcare for people suffering from painful conditions.

Background

Persistent pain has tremendous personal and financial impacts on the lives of those suffering, as well as on their friends, families, and society as a whole.1 In response to the ongoing opioid epidemic, the American College of Physicians has made changes to their Clinical Practice Guidelines to emphasize non-pharmacological interventions for persistent pain.2 Considerable evidence supports a biopsychosocial (BPS) approach, including pain neuroscience education (PNE), for individuals experiencing persistent pain.3–6 However, perceived challenges with the application of a BPS model, such as concern over engaging in difficult conversations about the impact of thoughts or emotions on pain experiences, may hinder implementation of PNE. PNE forces a paradigm shift toward a humanistic focus of care in which both the provider and patient are confronted with changes in relative roles, assumptions, and expectations. PNE necessitates collaboration around potentially difficult conversations that explore complex BPS factors.

Evidence-based approaches, such as Explain Pain and PNE, are emerging for how to engage in challenging conversations related to the multifactorial BPS elements of a persistent pain experience.5,7,8 The purpose of this narrative is to uncover and illuminate the personal reflections of a patient with multifactorial persistent pain, and of individual interprofessional rehabilitation team members who delivered the therapeutic intervention that featured PNE within a BPS framework. The aim is to deepen our understanding of how patients and interprofessional rehabilitation teams engage in PNE within a BPS model.

Interprofessional Team

Care for the following patient was delivered by an interprofessional team that consisted of physical therapists (Christina Malone, with consultation later provided by Marc Broberg), an occupational therapist (Pierre Clay), and a speech language pathologist (Tamara Backer). The reflections emphasized in this piece are those of the treating clinician authors (Broberg and Backer) with consultation provided by author Benjamin Boyd. A brief introduction of each team member follows.

At the time of this intervention, the evaluating physical therapist (CM) had over one year of experience working in the outpatient neurological setting in which the care for the present case was provided. Her experience and clinical interests in that setting included treating individuals with a variety of neurological problems including stroke, movement disorders, traumatic brain injury (TBI), and vestibular/balance disturbances. Working within an interprofessional setting was a relatively new experience for her, but she was interested in collaborative clinical care.

Prior to joining this interprofessional rehabilitation team, the occupational therapist (PC) had three years of experience working in an inpatient psychiatric setting and one year of experience working in both the inpatient and outpatient settings with patients who had neurological involvement, including TBI. Both of these settings involved an interprofessional clinical team. His clinical interests include vision therapy, stroke, and TBI.

TB, the speech-language pathologist (SLP), has been practicing since 2000. Much of her experience has been in the area of neurological rehabilitation, with an emphasis in TBI.

The consulting physical therapist (MB) had 14 years of clinical experience that included working within an interprofessional team in an inpatient setting with patients with a variety of neurological diagnoses, including TBI. For five years prior to engaging in the present case, his clinical focus had been on working with individuals who experience dizziness, often as a result of TBI. Just prior to the present case, he had become aware of contemporary pain science concepts and was interested in applying these concepts for his patients who experience both pain and dizziness.

BB has been a physical therapist since 2002, with clinical experience in a variety of outpatient orthopedic settings. He is currently an associate professor teaching in a physical therapy program and conducting research in neuropathic pain. In addition, he teaches continuing education for healthcare practitioners on treatment for neuropathic pain and pain neuroscience education.

Case Description

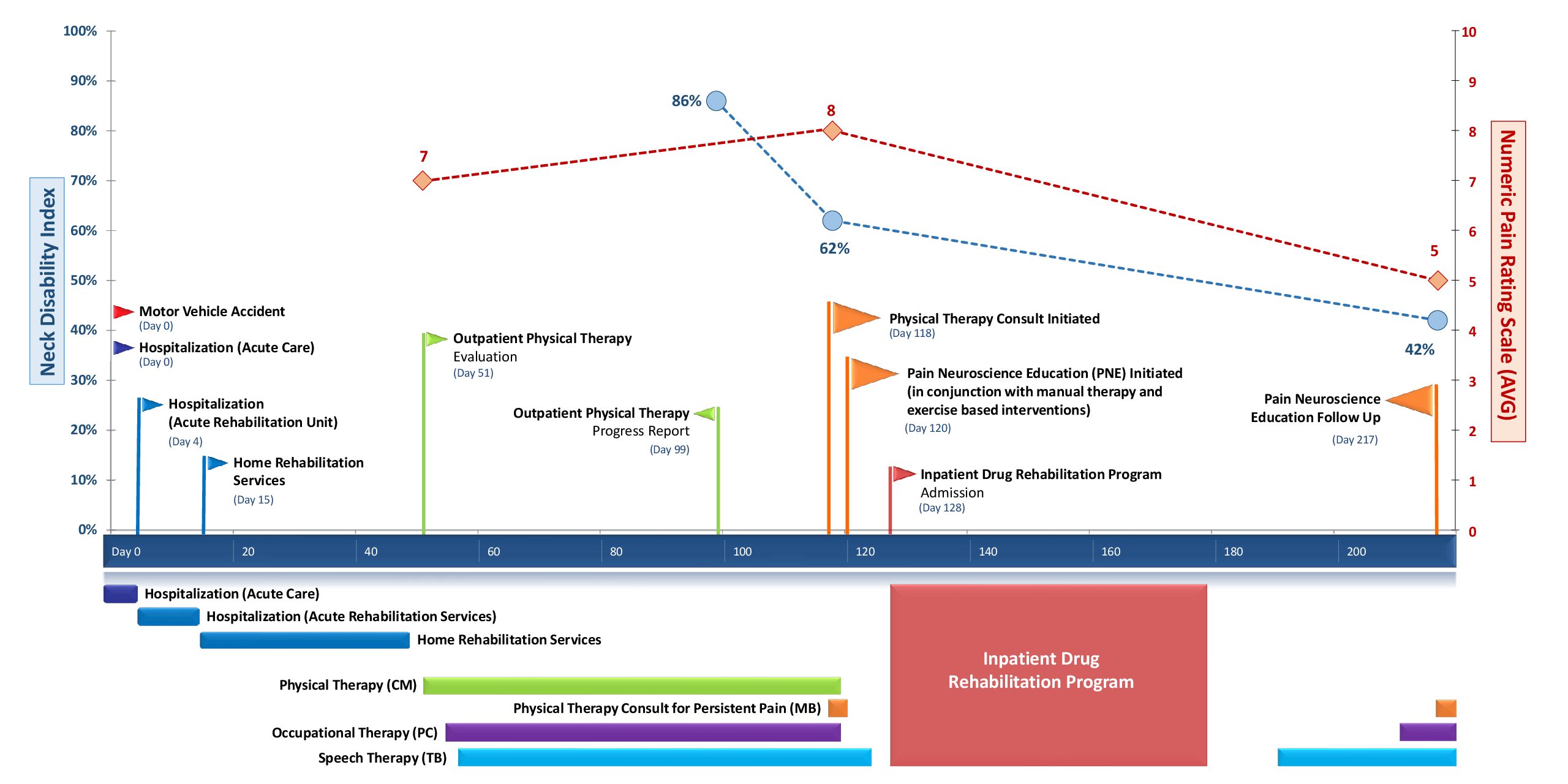

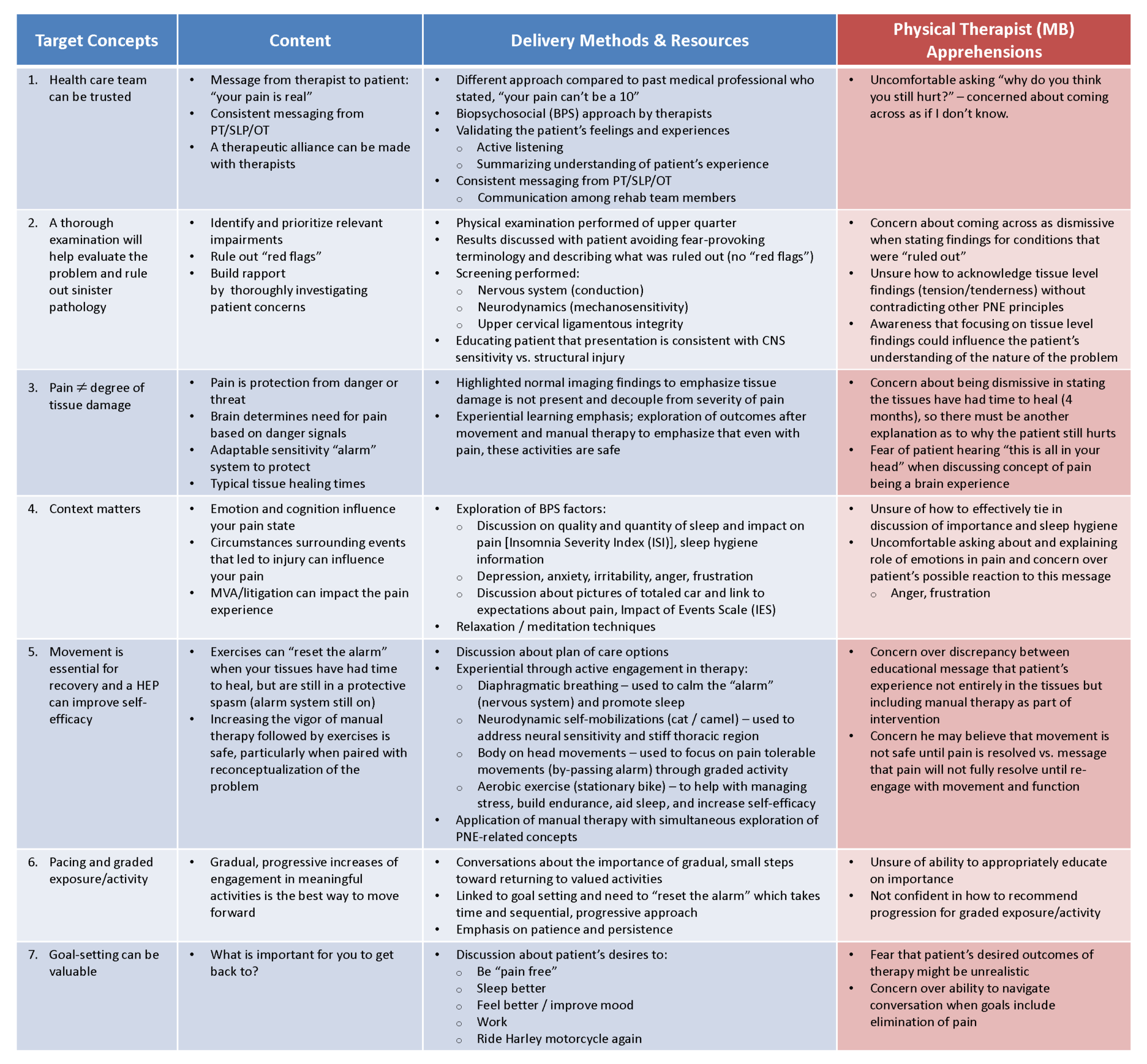

The patient whose case prompted this clinical reflection was a 24-year-old male with multiple traumas (TBI and multiple fractures) incurred during a “hit and run” automobile accident. He had a complex course of care that is illustrated in the Figure. Following his discharge from acute rehabilitation, pain emerged as a significant problem, with the patient reporting 12-15 intensity on the 0 to 10-point Numeric Pain Rating Scale (NPRS) during his home-based rehabilitation. His past medical history included: treatment for opioid and benzodiazepine addiction one year prior to this accident; multiple TBIs dating from a young age, with difficulties in school; post-concussive syndrome; and multiple orthopedic injuries and surgeries.

Upon discharge from inpatient and home-based rehabilitation, the patient began receiving outpatient physical, occupational, and speech therapies. The reflections that follow are related to this outpatient care.

The patient’s primary complaints were neck pain with associated sleep disruption and learning difficulties. His Neck Disability Index (NDI) score was 86%, indicating severe to complete disability.9 After approximately 2 months of physical, occupational, and speech therapy, an additional physical therapy consultation (performed by MB) was requested to address the patient’s persistent pain. Findings at that time included an improved NDI score (62%); however, the patient was still experiencing significant pain (averaging 8 on the 0 to 10-point NPRS). Additionally, the patient had poor posture (rounded shoulders, forward head), a provocative slump neurodynamic test (increased neck pain with seated slump coupled with unilateral knee extension), painful cervical and shoulder motion, hypomobility of the thoracic spine, and restricted soft-tissue mobility in the cervical and thoracic regions. Upper cervical ligament stability and a neurological exam of sensation and strength in the upper limbs were normal.

Pain Neuroscience Education Within a Biopsychosocial Care Approach

The speech language pathologist (TB) was familiar with PNE and provided initial education to address the patient’s pain. An additional consultation—requested by multiple members of the team and conducted by the physical therapist (MB)—indicated that the patient would benefit from a deeper understanding of his condition and associated biopsychosocial factors that were positively and negatively influencing his recovery. At this time, PNE was initiated to augment the patient’s ongoing therapies; he had received no prior therapy focused solely on PNE.

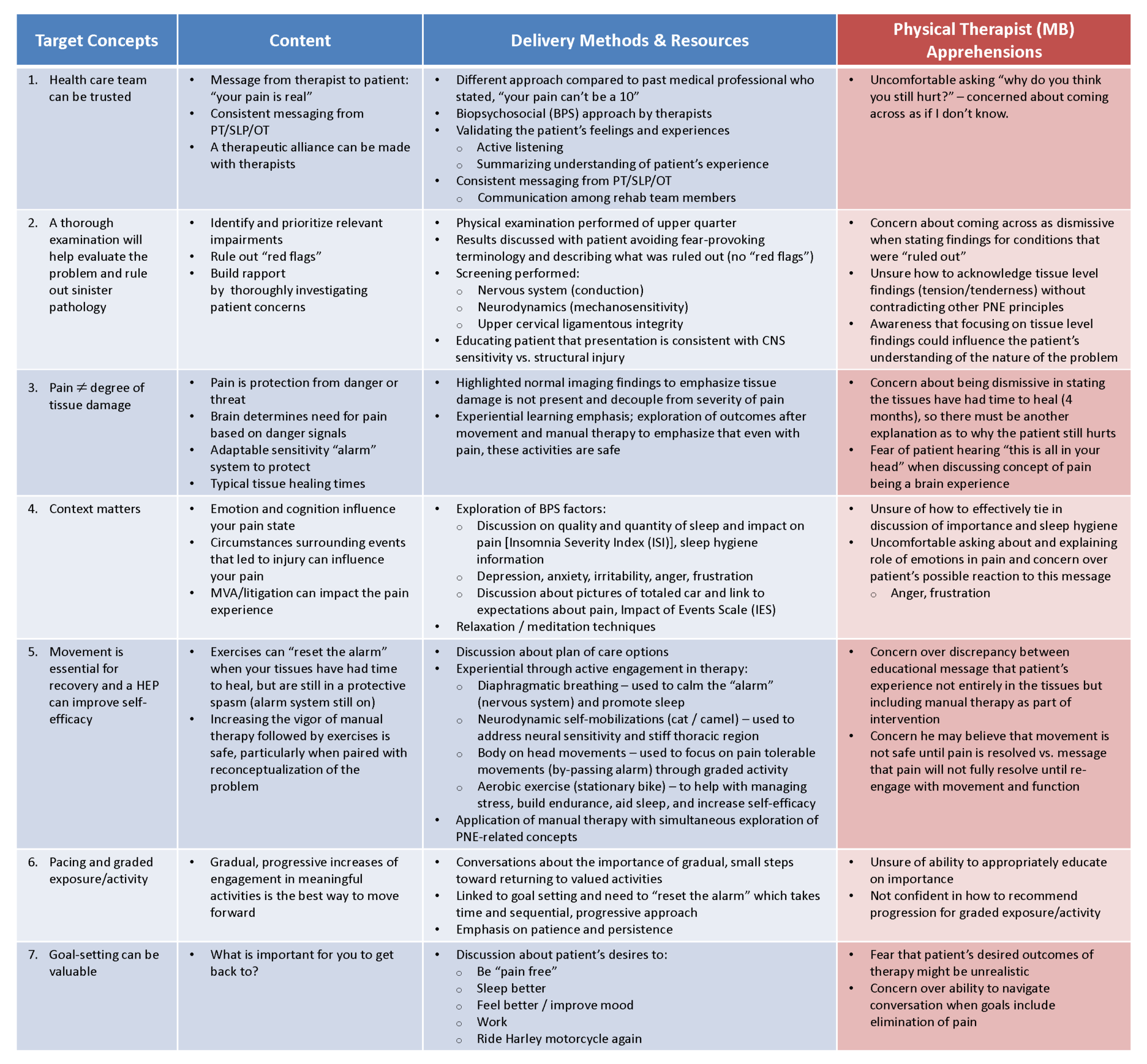

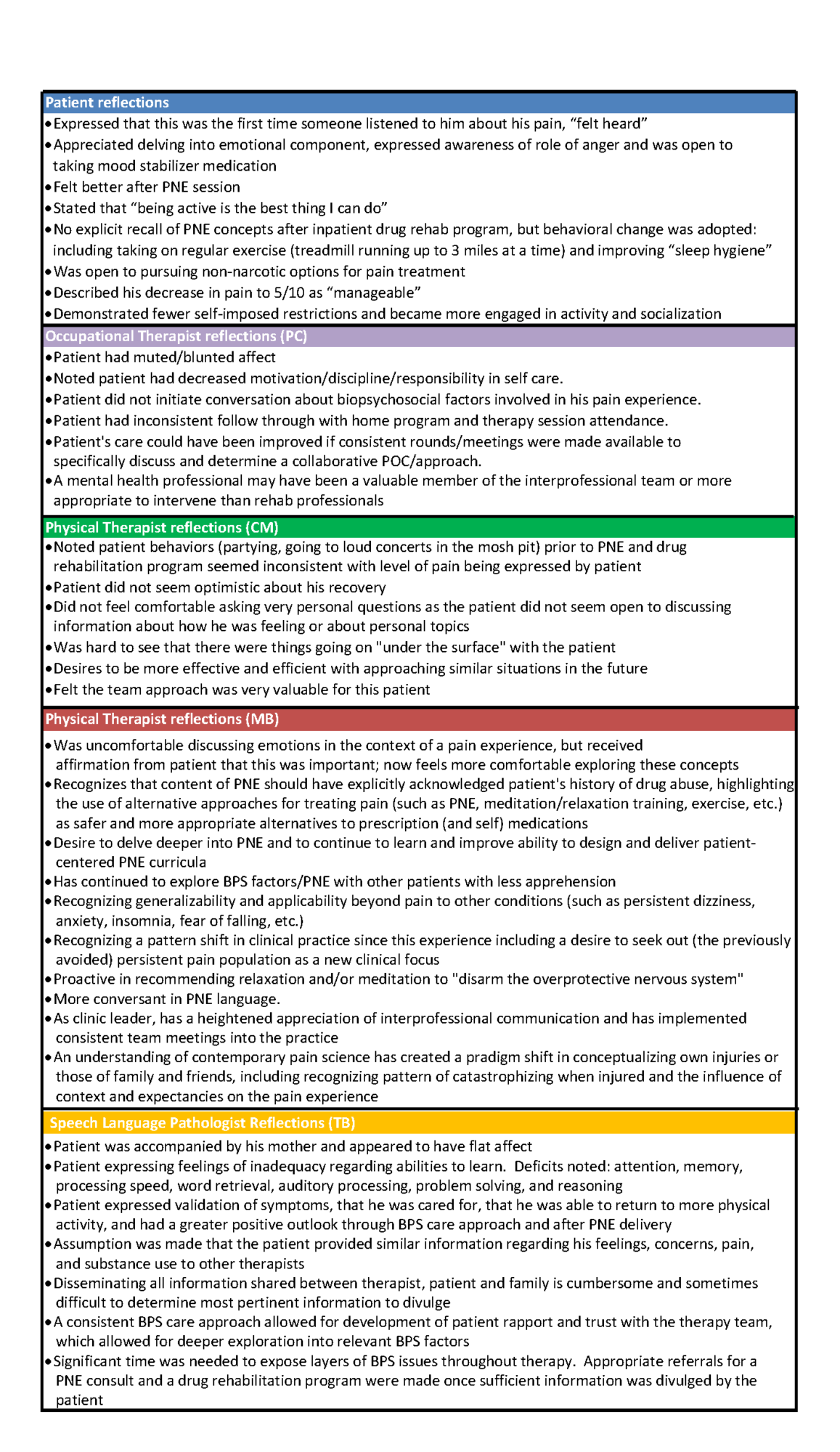

Key PNE themes, delivery methods, and additional resources utilized are delineated in Table 1. The physical therapist, MB, was an experienced clinician, newly familiar with PNE literature, but was a novice regarding implementation of PNE with patients. Both before and after patient interactions, MB self-reflected on his apprehensions about being able to deliver PNE content clearly, effectively, and efficiently (Tab. 1). The authors feel that the list provided from MB’s self-reflection (Tab. 1, Column 4) also represents common apprehensions among rehabilitation practitioners for the delivery of PNE within a BPS framework.

Table 1: Pain Neuroscience Education

Reframing Pain

Biopsychosocial factors involved in the patient’s condition were addressed through open discussions with him that explored and validated the patient’s perspective of his pain experience. PNE concepts were then introduced in an attempt to establish a BPS framework by which the patient’s pain experience could be reconceptualized. For example, pain was redefined as the body’s protective response to perceived threat, functioning as an “alarm” that does not directly reflect a state of tissue damage. The lack of physical abnormalities on the patient’s MRI findings was used to support this concept. This “alarm” metaphor, explaining how the body was reacting to his initial injury, was utilized for further conversations regarding other examination findings and patient experiences. Tissue responses, such as spasms and sensitivity to touch, were framed within the PNE narrative as evidence of this protective state.

The influence of emotion and expectations on the pain experience were acknowledged and discussed. Specifically, there was an acknowledgement of the emotional “charge” from the road rage incident in which the patient perceived he was deliberately run off the road. Photographs that the patient shared showing the severity of damage to his vehicle were used as examples for the patient of the relationship between expectations, perceived threat, and pain. The patient’s prior pain experiences and previous opioid abuse were not discussed at this time. A reflection of this omission along with other aspects of the patient’s PNE intervention are included in the Individual Team-Member Reflections section later in this article.

Multifaceted Therapy

PNE was delivered in conjunction with other therapies that included manual therapy, relaxation techniques, exercise interventions, cognitive and communicative strategies, and activities of daily living (ADL) retraining. The manual therapy was coupled with an explanation to the patient that despite the state of “protective spasm” (whereby his muscles were increasing their activity as a means of protection), it was safe and even beneficial to proceed with a more vigorous approach as these tissues were structurally robust upon physical examination. At this initial PNE-focused session, the patient was encouraged to actively engage in relaxation strategies, including diaphragmatic breathing and guided relaxation to help reset the “alarm.” Education on sleep hygiene was also provided (i.e., establish regular sleep/wake times, avoid caffeine after noon, engage in regular exercise, perform guided relaxation strategies at bedtime, limit the use of technology prior to bedtime). Active movement and postural exercises were provided in a graded manner to focus on progressive movement and self-efficacy. Self-mobilizations to address neurodynamic impairments and stiff thoracic tissues included quadruped whole-spine flexion-extension motions, progressing toward larger movements with graded increases in loading as tolerated. Cardiovascular exercise (stationary cycling) was utilized to help increase the patient’s activity level while managing pain and stress. During this initial PNE session, he was encouraged to engage independently in these strategies in a daily home-exercise program. These treatment approaches were paired with a consistent PNE message that movement was both safe and effective as a means of resetting the “alarm” and therefore decreasing his pain. The speech language pathologist (TB) was present throughout this physical therapy session and performed a subsequent debriefing with the patient during the ensuing SLP session.

Early in the outpatient rehabilitation process, the patient disclosed to TB that he had recently relapsed into substance abuse as a means of self-managing his pain. TB was intricately involved in conversations with the patient and his family regarding recommendations for seeking additional support for drug rehabilitation. The course of his outpatient therapy was subsequently disrupted by his admission to a 6-week inpatient drug rehabilitation program (Day 128 after initial injury; Figure).

Figure: Timeline and Outcomes

Outcome and Reflections

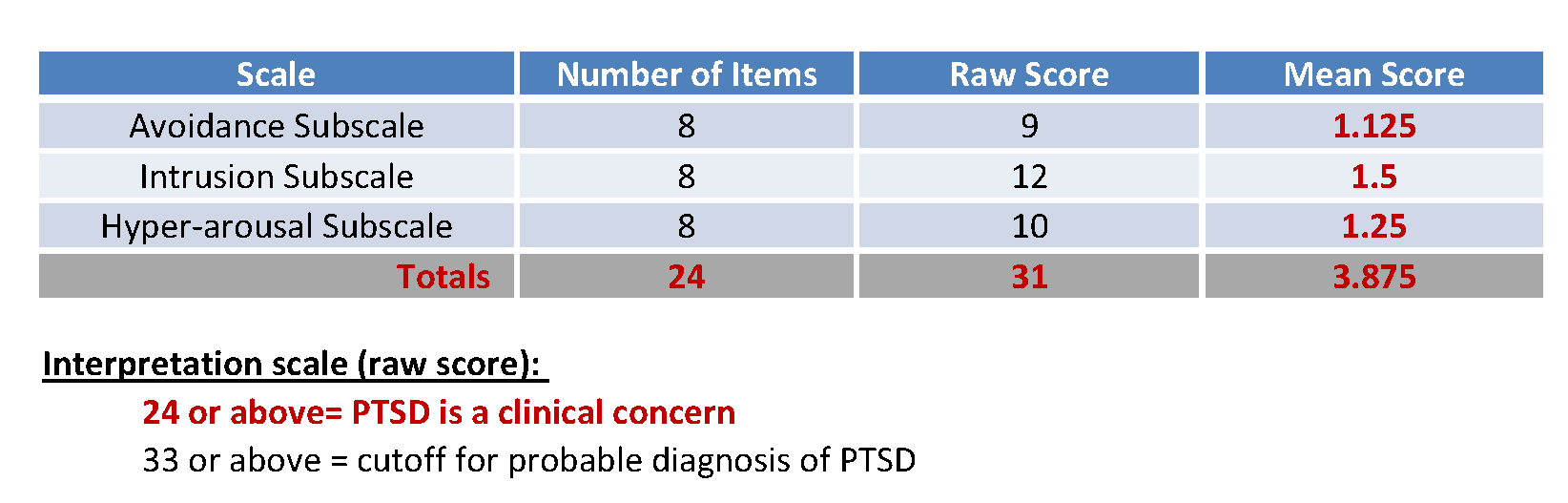

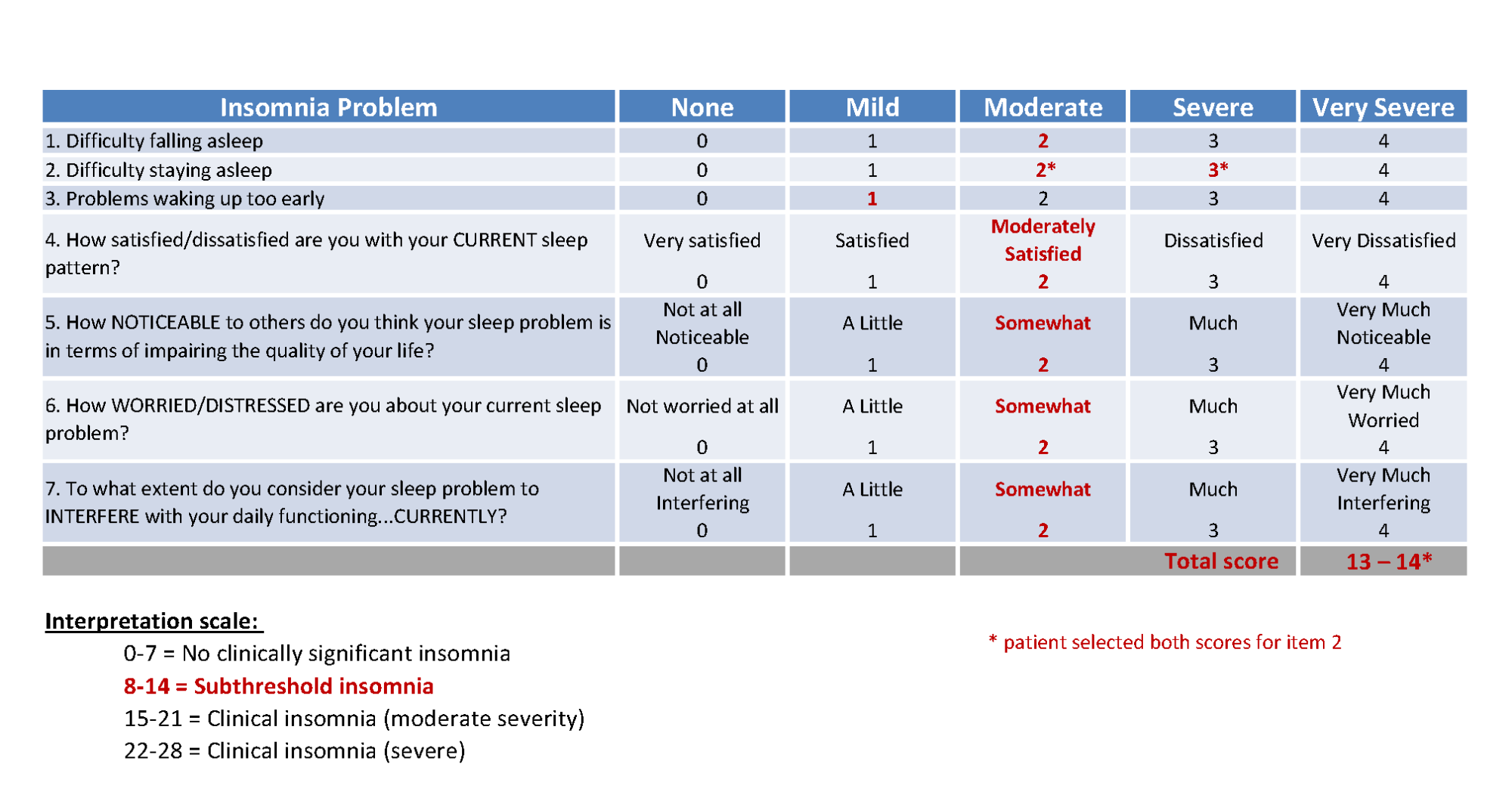

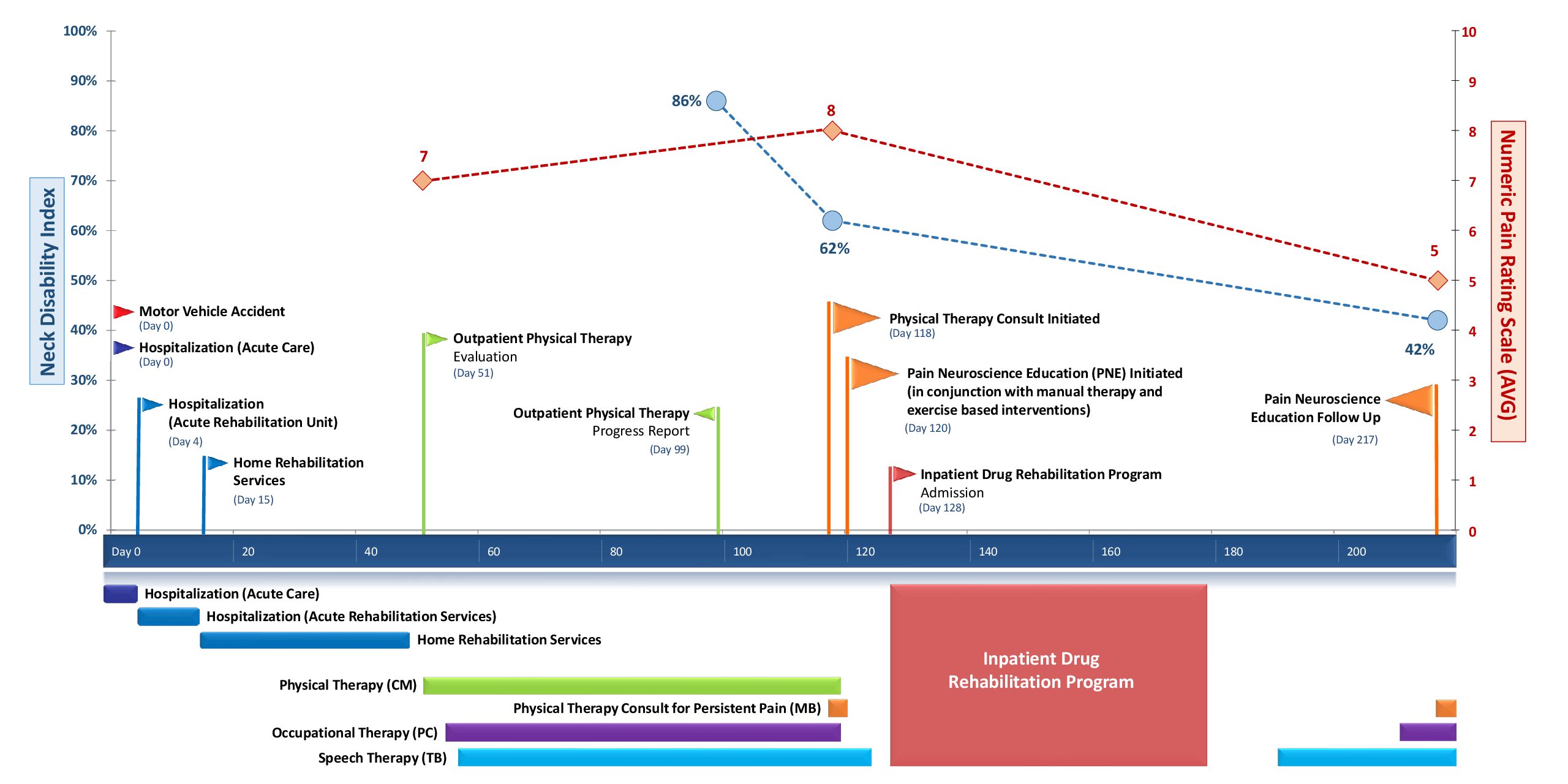

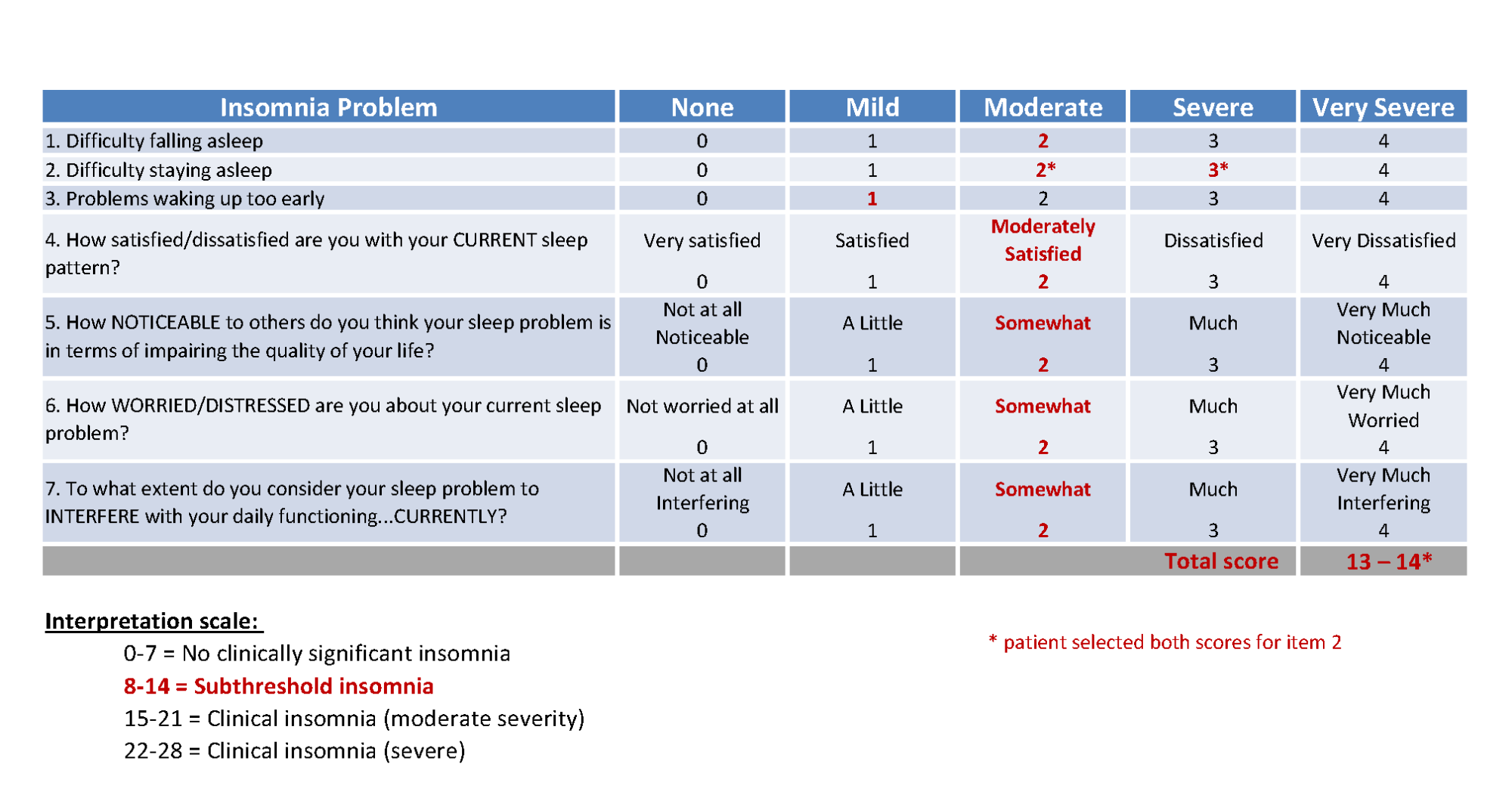

Upon discharge from the inpatient drug rehabilitation program, the patient returned to outpatient therapy, which included a PNE follow-up visit with physical therapist MB (Day 217). During this visit, the patient expressed that he was continuing to experience significant distress associated with his original injury, as demonstrated by the Impact of Events Scale – revised (IES-r)10 (Tab. 2), and significant sleep disturbances, as quantified by the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI)11 (Tab. 3). This information guided further PNE content and reinforcement of previous strategies that involved exercise, relaxation, and sleep hygiene.

Table 2: Impact of Events Scale (IES)

Table 3: Insomnia Severity Index (ISI)

Patient Impact

The patient’s feedback after the initial PNE session suggested that he valued the approach (Tab. 4). He reported a reduction in pain and expressed that he “felt heard” because this was the first time someone had listened to him about his pain. He reported that he appreciated delving into the emotional component of his situation. Interestingly, upon returning to outpatient physical therapy for PNE follow-up (Day 217) after discharge from his inpatient drug rehabilitation program, he was unable to directly recall any of the core PNE concepts; however, his behavioral changes were consistent with the aims of the PNE content. Specifically, his sleep hygiene and sleep quality had improved (although ongoing subthreshold insomnia was revealed by ISI), and he was actively engaging in exercise and relaxation techniques. He expressed that he was running on the treadmill for up to three miles at a time and stated, “Being active is the best thing I can do.” (Tab. 1, patient reflections.) His NDI had improved to 42% and he described his pain as “manageable” (averaging 5 on the 0 to 10-point NPRS – Figure.)

The patient also had been working with a psychiatrist to explore non-narcotic medications for pain and to address mood and anger issues. He was willing to continue exploring biopsychosocial aspects of his pain, stress, and sleep difficulties with his ongoing therapies. He indicated that he was participating in social events with his family, with improved dynamics, for the first time since his injury. He also exhibited greater participation in ADLs, expressed a desire to return to school, and was exploring new career pathways.

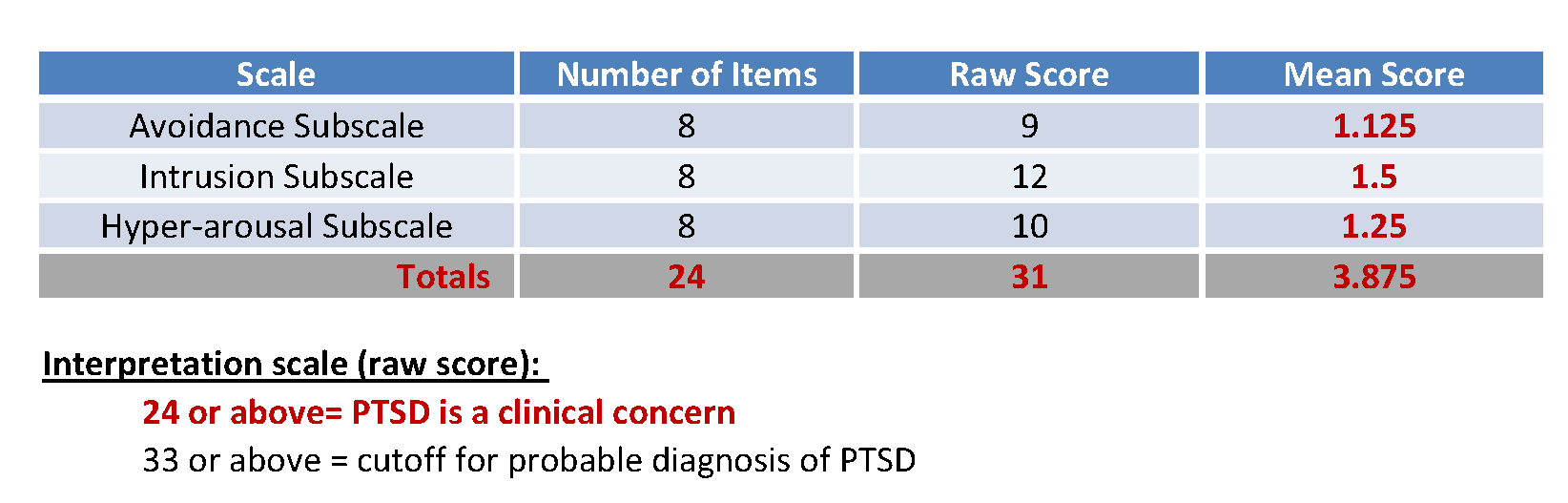

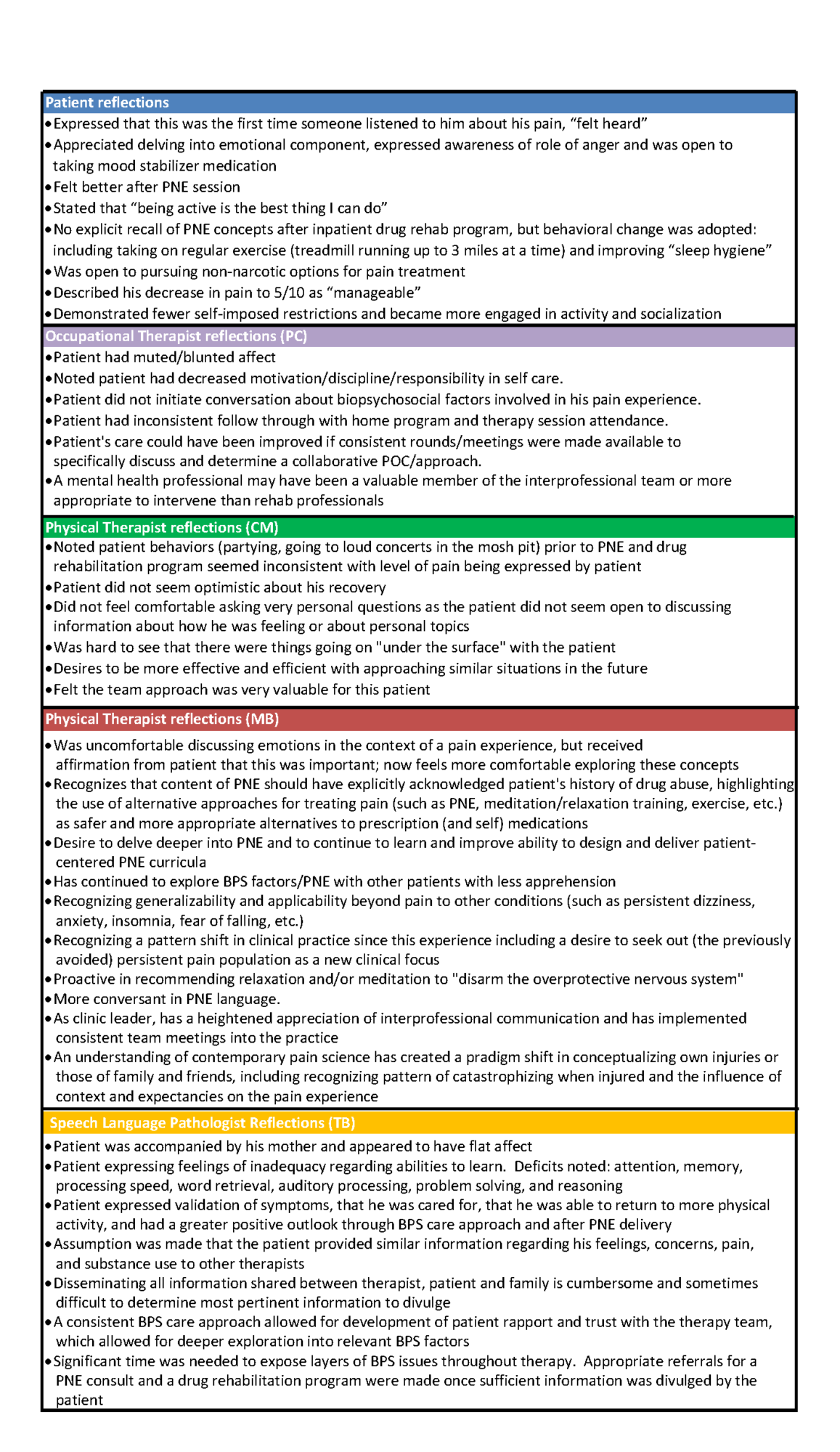

Individual Team-Member Reflections

Through evaluation of individual team-member reflections, the authors identified several themes regarding the patient’s need for a BPS approach that included PNE (Tab. 4). Multiple practitioners noted that while the patient reported significant pain, he did not seem very communicative in general, and particularly about any psychosocial factors of his situation. It should be noted that initial physical therapy and occupational therapy treatments focused on common post-TBI impairments, such as balance, dizziness, and function. The primary impetus to focus on PNE came from the speech language pathologist (TB).

Multiple factors may have influenced the decision to pursue a BPS approach. First, there is an inherent expectation of a communicative emphasis in SLP sessions that promotes dialogue, which could lead to a natural discussion of BPS elements of his pain experience. In contrast, he may have assumed physical therapy and occupational therapy interactions would not include discussing pain beyond its typical physical manifestations such as location and intensity. A lack of expressiveness by the patient may have served as a barrier for gaining a deeper understanding of the patient’s pain experience. Although TBI can create cognitive and communicative impairments, the patient was able to express to one member of the team (speech language pathologist TB) that his pain was a significant barrier to his recovery. This variability in the patient’s willingness to open up to different team members about the BPS elements of his experience may have led to the variance in therapeutic emphases for him.

Several barriers to engaging in both a BPS approach and PNE were identified by the physical therapist CM and the occupational therapist PC, including apparent inconsistencies between the patient’s behavior and his reported pain intensity. For example, on one occasion, the patient mentioned that he had been out “partying” and attended a concert where he engaged in dancing in the “mosh pit” the previous night despite reporting high levels of pain the next day. Additionally, there was a noted lack of follow-through with the patient’s home program.

The initial therapeutic approach may have been influenced by the physical and occupational therapists’ expectations of behaviors exhibited by patients with high levels of pain. These team members reflected that they did not feel equipped to manage the complexity of this patient’s psychosocial issues, and that he would have benefited from a psychologically-based intervention. In contrast, the speech language pathologist TB was experienced in the BPS approach and in nurturing the therapeutic alliance that allowed the patient to feel comfortable expressing psychosocial factors surrounding his pain experience. This therapeutic alliance facilitated the identification of the patient’s need for PNE.

During the initial PNE session, the physical therapist MB noted the patient’s flat affect, which he interpreted as the patient being disinterested or not valuing the approach. This contributed to further apprehension on the part of the physical therapist regarding the actual delivery of PNE content (Tab. 1). Despite the physical therapist’s perception, the patient recounted in a session with the speech language pathologist (TB) that he valued the PNE content and the BPS approach.

These reflections underscore how therapists’ expectations, apprehensions, and approaches to understanding the patient’s perspective can introduce bias that influences plan-of-care decisions. Humble self-reflection on the presence and influence of bias and therapists’ apprehensions is therefore recommended to ensure these factors do not ultimately affect patient outcomes.

This case also prompted team members to explore their PNE knowledge, fluency in PNE delivery, ability to individualize content, and their comfort with the challenging conversations related to a BPS approach and PNE interventions. Table 4 summarizes some key reflections from each therapist related to the PNE approach. This case prompted a desire for the consulting physical therapist (MB) to delve deeper into PNE design and delivery, while facilitating an interest in expanding engagement with patients affected by persistent pain. The experience of engaging in and reflecting upon the nuances of this case has led MB to recognize the generalizability of the PNE themes to other areas of rehabilitation (e.g., patients with persistent dizziness).

Reflection on this patient’s course of care, in light of the latent discovery of the patient’s relapse that occurred around the time of the first PNE session, led MB to realize he should have explicitly addressed the patient’s history of opioid abuse. MB did not initially engage the patient in a conversation about his past drug history because of a lack of comfort in broaching this potentially sensitive topic and a concern over the level of established patient rapport. Moreover, MB did not feel he had the background or resources to be effective in addressing this aspect of the patient’s history. As a result of this experience, MB has developed an interest in learning how to effectively address the complex nature of substance abuse within the scope of physical therapy practice.

Upon reflection, TB felt that the outcome of the case was successful in many areas. She agreed that the communicative nature of SLP practice coupled with cognitive exercises targeting executive function allowed natural opportunities for engagement in PNE. Despite the progress achieved, TB felt that hurdles remained between balancing trust with the client and divulging sensitive information to the rest of the team.

Table 4: Reflections on Pain Neuroscience Education (PNE), Biopsychosocial (BPS)

Reflections on Interprofessional Teamwork

Overall, the patient appeared to benefit from an interprofessional team approach. The approach included a BPS framework that led to the initiation of PNE and ultimately influenced the patient’s admission into an inpatient drug rehabilitation program. However, there were areas where communication and role delineation among the team could have improved team dynamics to better serve this patient. For example, not all members of the team were aware of the extent of the patient’s substance-abuse history and that a relapse occurred prior to the initiation of PNE. Enhanced team communication surrounding the patient’s substance abuse may have led to a more prompt referral to drug rehabilitation and integration of related content into the PNE discussions.

This case encouraged a deep exploration of team dynamics, facility infrastructure, and policy at this private, outpatient rehabilitation practice. For example, there was no formal relationship with a medical director, case manager, social worker, or psychologist within the setting of care surrounding this case. Moreover, the lack of reimbursement for team meetings or rounds in this setting, as exists in hospital-based inpatient rehabilitation facilities, places considerable pressure on the team and the facility. Most members of the rehabilitation team (TB, PC, and MB) had experience in hospital-based rehabilitation with a formal infrastructure that facilitates interprofessional teamwork.

For this patient case, team members had to communicate concerns with other team members on their own time, which was challenging given the variability of their schedules. Pursuant to this case, clinic leadership has implemented regular interprofessional team meetings in which team members are provided with a venue and structure that promote and encourage collaborative case discussions. This particular case was discussed by the team in an open and non-judgmental manner as a means to identify areas of improvement for the interprofessional team process. A culture that promotes mutual respect, openness, and professional humility has been promoted and modeled by the more senior-level therapists (TB, MB) through open discussion and vulnerable reflections on the current case.

These reflections are consistent with themes identified by Kvarnstrom12 regarding the difficulties within interprofessional teamwork—specifically, team dynamics, the knowledge contribution of each profession, and the influence of the surrounding organization.

Conclusion

The patient described in this study experienced significant reductions in pain and disability that exceeded the Minimally Clinically Important Difference (MCID) for NPRS (>1.3 points) and for NDI (>19%).13 He was more engaged with his family, work, and school after this course of care. Multiple factors were likely responsible for his positive outcome, including an interprofessional rehabilitation team approach, an inpatient drug rehabilitation program, patient commitment, family support, and possible spontaneous recovery. The addition of PNE within a BPS framework appeared to be a valuable component of this patient’s care and contributed positively to his ongoing recovery. Despite limited explicit recall of early PNE content, the patient appeared to value this approach, which possibly served to prime him for the behavioral changes emphasized in his drug rehabilitation program and the subsequent adoption of a healthier lifestyle.

Initiating PNE within a BPS framework in clinical practice is fraught with potential barriers and challenges associated with patient and therapist expectations and apprehensions. Acknowledgement of these apprehensions when engaging in PNE, paired with sound self-reflection that incorporates the patient perspective, can facilitate therapist growth in delivering PNE-based therapy within a BPS model, enhance interprofessional teamwork, and improve patient outcomes.

Member since 2019 | JM14274

Member since 2019 | JM14274

NO COMMENT