Physical Therapy at Bath War Hospital: Rehabilitation and Its Links to WW1

By Heide Pöstges, MSc, PT

The development of rehabilitation medicine accelerated during and immediately after the First World War (WW1). The war’s unprecedented scale of casualties, in combination with an increased survival rate of the severely injured due to medical advances, left a high number of soldiers with both mutilated bodies and minds—and posed a major challenge to orthopaedic medicine at the time. Rehabilitation practices attracted increasing interest in Great Britain when the War Office requested support for soldiers to regain the highest possible level of functioning—to either return to the battlefields or, at least, to reintegrate as productive civilians back into society.1

The watercolor painting Physical Therapy at Bath War Hospital (Fig. 1), by the artist Sarah Elizabeth Roberts Horton (E. Horton), depicts one of the very first physiotherapy departments in England. The following analysis of this painting puts early developments in rehabilitation practices into historical context, in order to take a critical look at underlying principles of rehabilitation that are often taken for granted today. Using rehabilitation as the analytical point of departure provides a new way to see and understand this work of art.

The Painting: A Unique Historical Record

Fig.1: Physical Therapy at Bath War Hospital. Watercolor by E.Horton, ca.1918. Wellcome Trust Library[ii].

The Artist

Sarah Elizabeth (Ettie) Horton (E. Horton) (1862-1959), the artist who had the keen insight to paint Physical Therapy at Bath War Hospital, was born in Australia of English parents. Her father was a mining engineer; her mother died when she was 11 years old. Horton was sent to England, where she was brought up by an aunt, received education, and became an artist. Horton established herself as an artist in London and moved later to Bath.3 She specialized in architectural watercolors of Bath and other towns; and, later in life, developed expertise working with gesso (a white paint base to prepare surfaces for paint). Horton’s work was regularly seen at exhibitions at the Bath Society of Artists; she also had paintings accepted for exhibitions at the Royal Academy and the Royal Institute of Painters.4 The Victoria Art Gallery in Bath currently holds 13 of Horton’s watercolors. The Watchman’s Box, Norfolk Crescent, Bath (Fig.2) is typical of her work.

Fig. 2: The Watchman’s Box, Norfolk Crescent, Bath. Watercolor by E. Horton. Victoria Art Gallery, Bath & North East Somerset Council. Image permission: Victoria Art Gallery, Bath & North East Somerset Council.

Analysis From a Rehabilitation Perspective

My initial viewing of the painting, Physical Therapy at Bath War Hospital, was through the eyes of a curious maverick with a professional background in both medical anthropology and physiotherapy. In my day job, I facilitate knowledge exchange between rehabilitation practitioners and their patients to support critical reflection and change in clinical practice. This explains my somewhat different point of departure compared to an art historian who would traditionally begin the research with a focus on objects and aesthetic principles.

At first, I was puzzled by the considerable difference between this painting and the artist’s architectural paintings that make up her body of work. Curious to find any hints as to what might have motivated Horton to paint one of the first physiotherapy departments in Britain, I tried to understand who she was as a person—including her social circumstances and life in Bath.

Secondly, my background in medical anthropology sparked my interest in investigating conceptualizations of healing and the body. I was intrigued to learn about the everyday experiences of those working in the Q Block and their patients, and how these experiences related to the wider social and political context of that time.

Thirdly, my current role as facilitator of change in rehabilitation urges me to think practically, which motivated me to explore what the history of rehabilitation can reveal about issues related to how rehabilitation is practiced today.

In this article, I show how these three points are related. I demonstrate that rehabilitation practices are socially situated, and that the concept of rehabilitation, with its origins in war medicine, is of a highly political nature.

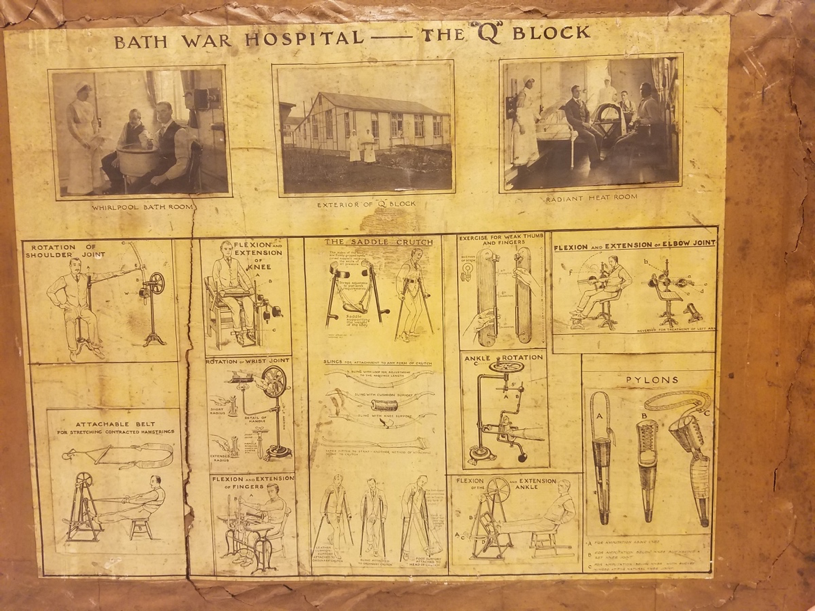

Bath War Hospital

The back of the painting (Fig. 3) provided a clue worth tracking down in my quest to figure out the artist’s motive for capturing this moment at Bath War Hospital. At the very top of the reverse side of the image are three photos stuck onto the frame, titled: Whirlpool Bath Room, Exterior of Q Block, and Radiant Heat Room. Below them are 13 workshop drawings of gymnasium equipment with the following descriptions: Rotation of shoulder joint; Attachable belt for stretching contracted hamstrings; Flexion and extension of knee; Rotation of wrist joint; Flexion and extension of fingers; The saddle crutch; Slings for attachment to any form of crutch (2x); Exercise for weak thumb and fingers; Ankle rotation; Flexion and extension of the ankle; Flexion and extension of elbow joint; and Pylons.

Fig. 3: Reverse of Physical Therapy at Bath War Hospital. Watercolor by E.Horton. Wellcome Trust Library.

Local newspaper articles from the period during and after the war offer insight into the possible source of the workshop drawings and photos, but also shed light on the social and political circumstances around the establishment of the hospital’s Q Block.

Bath had a longstanding reputation for innovative medical treatments, including hydrotherapy.5 The town’s geographical positioning and railway connections to the South coast were also ideal to transport convoys of wounded and sick soldiers from the British Expeditionary Force to the town for treatment. Due to a shortage of medical and nursing staff in the British army, the War Office was in need of civilian practitioners.1 In May 2015, the Mayor of Bath received a telegram from the War Office to provide additional hospital accommodation for wounded soldiers. After consulting with Bath hospital authorities, a committee was formed to negotiate with the War Office.6 The War Office agreed to fund the basic infrastructure of a new hospital, while the costs for its upkeep, and for more specialized and advanced facilities, were to be funded locally through volunteers and donations from residents.7

A local businessman, Alderman Cedric Chivers, paid for the entire cost of the building that became known as the Q Block, and sponsored the electrical and mechanical equipment inside it. Most of the appliances were manufactured by local engineers in Bath.8 The Bath Surgical Requisites Association, supported by 290 volunteers and temporarily housed in Chiver’s premises near the hospital, made many appliances for injured soldiers, including artificial limbs.9 The workshop drawings that are stuck to the reverse of the frame might be copies of drawings used in the Association’s workshops. Bath War Hospital was a local initiative, which makes it less surprising to find this painting in the body of art from a local artist who was concerned with motifs representing the town.

The hospital was opened in April 1916—the Q Block in November 1916. When the management transferred from the Ministry of War to the Ministry of Pensions, the facility was renamed the Bath Ministry of Pensions Hospital in 1919; it closed in 1930.10 Local journalists were only allowed to enter the facility after 1918. In March 1919, a local newspaper published four photos illustrating orthopaedic treatment carried out in the former Bath War Hospital.11

A Rehabilitative Moment Frozen in Time

The scene depicted in the left section of Horton’s painting, featuring a man exercising with a sculling apparatus in the front, a person on an exercise bike directly behind, and two men using mechanical handles fixed to the wall for forearm rotation, is almost identical with one of the published photos. The depiction of the masseuse in the center of the painting is remarkably similar to a masseuse in another photo; even the clock in the center back of the painting resembles the clock in the photo. These images served the artist most likely as models.

Since Horton could have only had access to the images after the end of the war, the painting came most likely into being in 1919 or later. Whether the three photos stuck to the back of the painting are part of the same series of images published in the newspaper is unclear. While the workshop drawings titled Flexion and extension ankle, and Flexion and extension of fingers resemble the images on the right side of the painting, it is possible that a previous owner or commissioner rather than Horton added them to the frame. This person probably had close links to the hospital, and also attached the label to the front of the wooden picture frame that honors J.Y.W. Macalister, Esq.— the Secretary and librarian of the Royal Society of Medicine who suggested investing in the electrical and mechanical equipment—and the donor of that equipment, Cedric Chivers.

Hospital as Military Machine

Horton’s painting depicts a spacious room with high ceilings and three large windows. The room serves as a physical therapy department for wounded soldiers, and holds electrotherapy equipment, whirlpool baths, mechanical exercise machines, and therapy beds. The main conditions treated in the Q Block were “wasted muscles, stiff joints, painful scars, in consequences of injuries received,” shell shock, and trench foot.12

Five men at the right side, two men at the left, and two at the center back of the image exercise using mechanical exercise machines. In the center, a masseuse mobilizes the hip and knee of a man lying on a therapy bed; behind her stands another woman in nursing uniform who seems to support a man using one of the mechanical exercise machines. Three men, seated in the back center left of the picture, wait for their turn. They appear engaged in activities even while they wait. One is depicted reading, and one is looking into the center of the room with a booklet on his lap; the third is half hidden behind a dividing wall.

Behind the therapy bed in the center right, a man is seated with his arm in a whirlpool bath resembling the bath in one of the photographs stuck to the back of the painting. On the wall to the right is a panel for control of magnitude and type of electric current. Most of the men are fully dressed wearing blue suits, white shirts, and red ties. War and military hospitals provided recovering soldiers in Britain with these blue, often ill-fitted, hospital suits that became known as “hospital blues.”13 The uniforms identify the men in the painting as soldiers still subject to military discipline, and give a sense of institutionalization. The following lines from a poem written by a soldier for the hospital’s magazine that was published by the soldiers themselves, confirms this reality:

When the M.O. makes a visit,

Silence! Do not make a din,

Keep the bedclothes nice and tidy –

All the ends tucked nicely in;

Keep your locker neat and shining,

Don’t drop paper on the floor,

When you get your daily ration,

Do not ask for any more.14

The male figure facing the viewer in the middle right section of the painting is Dr. King Martyn, the physician in charge. He overlooks the application of light therapy for a man who seems so severely injured that two nurses are needed to carry out the treatment—one to prop him up on a chair and the other to apply the bath. A dominant vertical post frames the scene.

Dr. Martyn considered good treatment outcomes for wounded soldiers as “being able either to rejoin their units or perform munition or other work.”12 These therapy aims reflected the then overriding military agenda of rehabilitation. The increase in the number of wounded soldiers leading up to 1916 encouraged the War Office to boost investment in therapies that promised to restore function in wounded bodies, enabling men to either re-join the military forces or find long-term employment as civilians.13 Bath War Hospital was built as a result of this additional investment.

Dr. Martyn lamented “the shell-shock element producing the unconscious malingerer, and by the fact that whereas the civilian is, as a rule, most anxious to get back to his work, many of these poor soldiers do not, or cannot, co-operate with the physician.”12 His ideas about the necessity of active engagement in therapy stood in sharp contrast to the soldiers’ common belief in well-deserved rest.13

Horton’s watercolor serves as a visual record of the entanglement of medicine in warfare, which was also a concern in the local media at the time. Critical voices associated the rehabilitation provided in the Q Block with war politics: the “war hospital was under war office control and the war office was essentially a military machine.”15

Masculinity in Crisis

Advancements in technology had paved the way for modern industrial warfare, causing devastation and violence of unprecedented scale during WW1. Technologies producing injury and death rather than improvements seemed a huge setback for modern life often defined by “development” and “progress.” Mutilated male bodies and shell shock exacerbated long-held concerns of mental and physical degeneration.16 Alongside economic and social upheavals,17 fears about racial degeneration and a decline of heroic manliness—which was thought to be needed to fulfill imperial purposes—appeared to shatter the dream of the British Empire. Medicine had long contributed its part to these public debates by advocating for compulsory military training and health programs for the poor to ensure adequate manpower for the army.18 The emphasis on normative heroic ideals of manliness through militarized medicine at Bath War Hospital is evident from another verse of Ellerton’s poem:

You must shave before nine-thirty –

You’ve an awful dirty face;

Visitors will soon be coming,

Please do not be a disgrace:

When you get your daily dressings,

Just be silent as you can,

Do not jump if it should hurt you,

Be a soldier, be a man!!14

Here, the nurse questions his masculinity should he disregard her standards of cleanliness and openly express pain. Her expectations of manliness represent regulations from eighteenth-century hygiene movements and a Victorian and Edwardian ideal of masculinity defined by military heroism.18 This poem illustrates how wounded soldiers struggled with the incompatibility between social expectations of manliness and their physical and mental injuries.16

While medical agendas shaped normative ideals in society, the very same ideals informed the culture of medicine. Medicine had, historically, allied itself, for the most part, with the military as a means to gain recognition as a profession and to preserve medicine as a male domain. As a result, medical practice followed a masculinized vision of medicine based on values framed in military language—such as active, brave, and courageous.18

A Painter’s Statement

Horton, however, puts two women wearing nursing uniforms into a central position in her painting. The woman who mobilizes a soldier’s leg in the foreground of the picture is the chief nurse and masseuse Marjorie Cook. Her expertise in electro-mechanical therapy—and her adaptations to electrical appliances that helped optimize their effects—were regarded highly in Bath.8 The depiction of Cook and the men she is treating in the painting is identical with a photo from inside the Q Block published in a local newspaper. The journalist describes the image as follows: “the sister-in-charge (Miss M. Cook, A.R.R.C.) is shown exercising the patient’s weak leg.”11 The photo and the artist represent Cook as active, while the man lies in a passive position. The image challenges traditional power relations by contradicting the notion of Victorian masculinity, according to which the attributes active and strong are associated with men, while women are considered passive and weak.18

By placing two women at the center of the painting, Horton presents them as having a pivotal role in war medicine, which contradicts more common views of the nursing discipline as a profession of considerably lower social status than the higher (male-dominated) stratas of medicine. The image suggests that expanding their expertise in new therapy methods that restore the physical functioning of soldiers enabled them to secure a higher reputation by acting more “man-like,” highlighting their invaluable contribution to the war. The image can, therefore, be perceived as a feminist painting.

Building a Modern Future on Classical Ideals

The vast number of wounded soldiers in WW1 accelerated the development of new rehabilitation methods.1 The most pressing issue at the time, besides finding pragmatic solutions to overcome the tremendous human suffering caused by industrial warfare, was the need to identify ideals for a better future. Common concerns about racial degeneration and the decline of masculinity prepared the ground for a return to ancient Greek beauty ideals of the male body that seemed a promising response to the desire to reconstruct the wholeness of bodies and restore stability in society.16 Horton’s painting of the Q Block at Bath War Hospital embodies these very ideals for a better future and reveals how gender concepts framed early developments in rehabilitation, particularly the newly emerging discipline that is known as physiotherapy today.

Horton’s use of muted, warm colors creates a harmonious effect. All the attending professionals are bathed in sunlight coming in from the large windows, as if the war had never happened. The sunlight coming through the windows is perhaps a visual reference to healing attributed to the three natural remedies of air, sunlight, and water—a concept that originated in the Alps and found supporters among the British middle-class in the years leading up to WW1.5 The electrical appliance for light therapy to the right in front of the doctor was a modern way of extending this approach.

Applying natural remedies from outside the body, as opposed to relying on the therapeutic effects of intervening inside the body, have been popular in Greece, Rome, and other parts of the world since ancient times.5 In keeping with the classical ideal of harmony, the aim of these physical therapies was to reconcile tension between body and mind. The focus on the person as a whole made the application of these therapy forms attractive for the treatment of soldiers with permanent injuries, since the medical emphasis on improving the function of individual body parts failed to deliver satisfying outcomes.16

European Innovations

In European towns where medical doctors had a strong influence on the spa culture, a systematic approach to physical therapies that included a combination of bathing, electrotherapy, exercising, and massage had become part of the treatment provided in hospitals by the end of the 19th century. In the 1880s, the British Medical Journal (BMJ) began to publish articles on the clinical effectiveness of massage; hospitals across Great Britain employed an increasing number of masseuses. The first masseuses were nurses who completed additional training provided by physicians or senior masseuses at mainly London-based training schools.

In 1895, the Society of Trained Masseuses was formed as a branch of the Midwives’ Institute and Trained Nurses’ Club. This organization was the precursor of the Incorporate Society of Trained Masseuses (1900), the Chartered Society of Massage and Medical Gymnastics (1920), and the still-existing Chartered Society of Physiotherapy (1944). While early members were predominantly nurses, an increasing number of women began to take up massage—including the application of various physical therapies—as a career on its own. Electrotherapy became increasingly popular to treat symptoms attributed to nervous ailments, which were believed to be a side-effect of industrialization and modern life. During the war years, the scope of its application broadened rapidly to include, for instance, testing and stimulating muscles.5

Advances in exercise programs and massage therapy were strongly influenced by the “movement cure” developed by the Swedish physical educator Dr. Pehr Henrik Ling, who distinguished between active movements encountering resistance and passive movements performed on the body, such as rubbing—a precursor to massage. Swedish physician Dr. Jonas Gustaf Wilhelm Zander took Ling’s approach a step further by developing the first mechanical equipment to control the exact weight-resistance needed to optimize development of individual muscles. He created gymnastic appliances for different movements; his equipment collections became internationally known as Zander Institutes.19 Bath War Hospital was one of the few hospitals in Britain in possession of an almost complete Zander Institute.12 Some of these machines are shown in the painting.

Innovation at Bath War Hospital

Many soldiers came to Bath War Hospital with severe injuries that caused muscle weakness and limited mobility. Zander machines enabled them to gradually improve their physical strength and range of movement, easing the transition to outdoor team sports, which were closely connected to national identity in Britain and believed to reconnect soldiers with their civilian lives.1 Dr. Martyn said the participation in regular sport activities at Bath War Hospital “give[s] free play to the arm and shoulder muscles” and noted the soldiers’ willingness to get involved.12 The hospital also organized annual public sports contests for patients and staff, which were attended by large crowds of Bath citizens.20

The painting helps viewers see early developments in rehabilitation as attempts to restore damaged masculinity through providing opportunities for men to get active and rebuild their physical strength. Horton depicts all soldiers, including those waiting for their turn, as engaged, which contradicts Dr. Martyn’s perception of uncooperative patients.12 In so doing, Horton creates an idealized version of soldiers recovering from injuries during WW1, which bears a certain resemblance to ancient Greek sculptures that represent male bodies as physically strong and in motion.21 Both active and passive movements helped to heal the body and mind as “muscles became markers of men’s rehabilitation and civilian reintegration, showing that the fragmented man could be restored through classical ideals of wholeness.”16

The similarities between the photos published in the local newspaper and the painting reveal the meticulous care the artist took to achieve a realistic representation of the electrical and mechanical equipment in use at the hospital. While her quest for realism represents classical ideals, the painting itself shows the potential of technology to heal as opposed to causing destruction and violence. Here, reconstructing the body is aligned with modernity.22 During the war, the Q Block and its then state-of-the art equipment, received many visits from respected experts—and royalty, including King George V and Queen Mary, who were impressed with the innovative treatments provided.6 The artist merges classical and modern values to create aesthetics of movement that counteract the brutal reality of warfare and turn efforts to restore the male body into a symbol for healing the nation.16

Rehabilitation as Sacrifice

Horton painted the soldiers’ uniforms in a strikingly strong blue, perhaps identifying them as “Tommies”—patriotic heroes. The image of recovering soldiers actively exercising or having their limbs exercised by masseuses draws attention to their resilience as well as to their weakness and, ultimately, to their continuing sacrifice for the nation. Horton’s painting combines imagery of passive movement with heroic images that hide any form of strain or discomfort. The facial expressions of all figures in the image are shown in an emotionally neutral way, which idealizes the beauty of restoring and re-activating the male body. The image can be interpreted as an example of attempts at the time to re-evaluate endurance as courageous, softening the concept of heroism without posing a serious challenge to the normative masculine ideal.23 In so doing, Horton contributes to the nation’s collective memory of overcoming devastation by returning to classical ideals of the male body.

At the same time, the imagery of heroic sacrifice provides meaning to the suffering not depicted in the painting. Many soldiers admitted to the hospital were, for instance, Australians with little or no previous connection to the residents of Bath.10 The hospital, however, only existed due to the remarkable efforts of local residents who funded, equipped, and staffed it following an appeal to the public that read, “…local help must supply these men, who have sacrificed themselves for their country.”7 Many local people sacrificed their own health as a result. Although Bath War Hospital was one of the best equipped hospitals in the country,8 the Royal United Hospital in Bath lacked resources to provide the most basic care to the general public.24 The remarkable achievement of establishing one of the best rehabilitation facilities in the country came at considerable cost to the local population. The civilian contribution to Bath War Hospital was, nevertheless, a chance for civilians to become heroes themselves. A review of the hospital’s history in the local media at the time reads: “The Combe Park Institution…has had associated with it a degree of self-sacrifice and enthusiastic, sustained voluntary service by almost every class of the community that has not been equalled within living memory.”10 The many civilian volunteer hospitals across the country enabled civilians to contribute to the war efforts, which made medicine—with its newly developing specialization to help reconstruct soldier’s bodies—a main driver behind mobilizing the whole nation for war.13

Rehabilitation as a Means to ‘Return to Order’

Horton’s painting is part of a wider societal trend throughout the western world of reviving classicism as a form of expression and guidance for modern life at the beginning of the 20th century. The French artist and poet Jean Cocteau is believed to have coined the term, “return to order” (retour à l’ordre), which has become widely used to describe the European art movement following WW1.25 Avant-garde artists such as Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso returned to forms of realism and classicism as an artistic means to restore a sense of reassurance in times dominated by feelings of distress in the aftermath of WW1.26 Greek ideals of masculine beauty manifested in the numerous war memorials erected across Britain. The notion of heroic self-sacrifice helped to make the irreparable harm industrial warfare had done to body, mind, and civil life more bearable and meaningful. At the same time, the idealized active and reconstructed male body helped to put an end to the devastation by rendering individual suffering invisible, thereby avoiding the feared decline in masculinity.16 Horton’s painting and its aesthetics of movement can be understood as an early form of images depicting what Carden-Coyne calls “healing aesthetics,”16 in which male beauty is defined as white – marble – muscular. Idealized imagery of such bodies intended to help the nation as a whole come to terms with the consequences of the war and reconstruct a civilization thought to be lost.

Conclusion

Early developments in rehabilitation, particularly physiotherapy, took place against this background of war and recovery. Due to medicine’s strong entanglement with the military, rehabilitation as practice helped to mobilize the nation for war. It was mainly grounded in a masculinized vision of medicine framed around activity, courage, and bravery, as opposed to domestic values such as peace, compassion, and care.18 The return to classical forms of the male body in art further reinforced the paradigm of normalization in accordance with stereotypes of manhood—which helped promote physical rehabilitation as an emerging discipline. Physical Therapy at Bath War Hospital urges us to take a closer look at how political developments and social expectations have informed rehabilitation practices.

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to thank Dr. Francis Duck for being so generous in sharing his historical resources and knowledge about Bath War Hospital. A big thanks is offered as well to Jon Benington, manager at Victoria Art Gallery, for his useful guidance.

References

- Anderson J, Perry HR. Rehabilitation and restoration: orthopaedics and disabled soldiers in Germany and Britain in the First World War. Medicine Conflict Survival. 2014;30(4);227-251.

- Wellcome Trust Library. Physical Therapy at Bath War Hospital. Watercolour by E. Horton (no. 44761i). Available at: https://search.wellcomelibrary.org/iii/encore/record/C__Rb1202573. Accessed January 10, 2019.

- [Anonymous reporter.] Bath Artist. An Appreciation of Late Miss E. Horton. Bath Wilts Chronicle. 1959;April 14.

- [Anonymous reporter.] Bath artist’s success. Picture accepted by Royal Academy. Bath Chronicle Herald. 1934;May 5.

- Barclay J. In Good Hands: The History of the Chartered Society of Physiotherapy, 1894-1994. Oxford, England: Butterworth-Heinemann; 1994.

- Bannatyne GA, ed. The Bath Bun. The Book of the Bath War Hospital. Bath, England: The Herald Press Bath; 1917.

- Bath War Hospital. An appeal. Bath Chronicle. 1915;Dec 25.

- Healing the wounded. Electrical equipment at Bath War Hospital. Bath Chronicle.1917;Apr 21.

- Bath Surgical Requisite Association. Bath Chronicle. 1919;Apr 5.

- Nearly 40.000 patients. The great work of the Bath War and Pensions Hospital ending early next month. Bath Chronicle Herald. 1928;Dec 29.

- Series of photos illustrating orthopaedic treatment carried on at Bath War Hospital. Bath Chronicle. 1919;Mar 22.

- Martyn K. D. King Martyn (Bath). Proc Roy Soc Med; Section of Balneology and Climatology. 1917;10:19-21.

- Reznick JS. Healing the Nation: Soldiers, Caregivers and British Identity. During World War I. Manchester, England: University of Manchester Press; 2005.

- Ellerton HW. (1917). United Verses. Life in Hospital. In: Bannatyne, GA, ed. The Bath Bun. The Book of the Bath War Hospital. Bath, England: The Herald Press Bath; 1917:123.

- Bath local tribunal. Bath Chronicle. 1916;Mar 18.

- Carden-Coyne A. Reconstructing the Body: Classicism, Modernism, and the First World War. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press; 2009.

- Ledger S. In darkest England: the terror of degeneration in fin-de-siecle. Britain Lit History. 1995;1:71-86.

- Brown M. “Like a devoted army”: medicine, heroic masculinity, and the military paradigm in Victorian Britian. J Brit Studies. 2010;49(3):592-622. doi: 10.1086/652000.

- Ueyama T. Capital, profession and medical technology: the Electro-Therapeutic Institutes and the Royal College of Physicians, 1888-1922. Medical History. 1997;41:150-181.

- Bath War Hospital Sports. Large crowd witnesses keen contests. Bath Chronicle;1919:Aug 2.

- Jenkins I. Defining Beauty: The Body in Ancient Greek Art. London, UK: British Museum Press; 2015.

- Zweiniger-Bargielowska I. Managing the Body: Beauty, Health and Fitness in Britain, 1880-1939. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press; 2012.

- Mosse GL. The Image of Man. The Creation of Modern Masculinity. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1997.

- Royal United Hospital. Bath Chronicle. 1917:Feb 3.

- Cocteau J. Le Rappel à L’ordre. Paris, France: Stock; 1948.

- Tate Museum. Art term: return to order. Available at: https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/r/return-order. Accessed Jan 22, 2018.

Member since 2019 | JM14274

Member since 2019 | JM14274

NO COMMENT