Through the Lens of Positive Aging

By David W. M. Taylor, PT, DPT, Leslie F. Taylor, PT, PhD, MS, N. Beth Collier, PT, DPT, EdD, and Susan W. Miller, B.S. Pharm, PharmD

Introduction

The number of older adults seeking quality healthcare continues to increase in the United States and globally.1 Contemporary professional health sciences education should prepare future providers to meet this need using evidence-based approaches in didactic and experiential learning experiences that mitigate barriers to care and promote optimal outcomes. The need for competent healthcare providers to provide quality care for older adults (persons > 65 years of age) is not new, and emphasis on the care of older adults varies across health sciences education programs and disciplines.2,3 This brief report will describe a humanities-based Interprofessional Education (IPE) activity intended to support health professions students’ abilities to think about and see older adults as people first, not patients. Promoting students’ empathy toward older adults and contemplating ageism in a safe space were additional considerations.

Age-Friendly Health Systems and Care

Quality healthcare for older adults is complex and requires a competent and engaged interprofessional team.3 To address this need, the “age-friendly health system” initiative and “4Ms” framework were developed by the John A. Hartford Foundation and Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI), in partnership with the Catholic Health Association of the United States.4 IHI defines age-friendly care as healthcare that focuses on an older person’s specific needs and wants. This evidence-based framework considers a set of essential elements known as the 4Ms in each healthcare encounter to enhance the older adult’s quality of life.4 The initiative seeks to better meet the healthcare needs of an aging society across settings where healthcare is delivered. Central to the initiative is that value is delivered to patients, families, caregivers, healthcare professionals, and systems.

The 4Ms Framework

Provision of age-friendly care requires consideration of the 4Ms framework at each healthcare encounter:

- What Matters

- Medication

- Mentation (now Mind)

- Mobility

What Matters is to know and align care with each older adult’s specific health outcome goals and care preferences including, but not limited to, end-of-life care, and across settings of care.

Medication, if medications are necessary, includes using Age-Friendly medications that do not interfere with What Matters, Mentation (Mind), or Mobility.

Mind (Mentation) focuses on the prevention, treatment, and management of depression, dementia, and delirium across settings of care.

Mobility ensures that older adults move safely every day in order to maintain function and do What Matters.

Adoption and application of the evidence-based 4Ms framework and the age-friendly health system initiative show beneficial outcomes for older adults, their families, care delivery systems, and providers. Preparation for practice in an age-friendly health system as a member of the interprofessional team necessitates introduction of age-friendly care and the 4Ms in health professions education. Awareness of modifiable barriers to the delivery of age-friendly care should also be addressed, such as ageism and reduced empathy in healthcare.

This project endeavored to apply the 4Ms framework to an IPE activity using a health humanities approach.

Addressing Ageism

Ageism is stereotyping, prejudice, and discrimination against individuals, groups, or ourselves based on age.5 It is a paradoxical construct, in that younger people may discriminate against their future selves.6 Ageism can take many forms, including prejudicial attitudes, discriminatory practices, or institutional policies, laws, rules, and practices that perpetuate stereotypical beliefs and disadvantage individuals because of their age.7 Other types of discrimination interact with ageism, including ableism, sexism, and racism, compounding disadvantage for older persons and compromising their health and well-being.8

According to the World Health Organization (WHO) Global Report on Ageism, one in two people are ageist against older people. Ageism results in negative consequences across multiple sectors of society including the workplace, media, the legal system, and healthcare.8 Risk factors associated with ageism in healthcare include higher rates of illness, lower life expectancy, poverty, and higher healthcare spending5,9 Individuals with ageist beliefs, decisions, or actions may or may not be conscious of their own biases. Everyone has implicit biases that occur automatically as the brain makes judgments based on past experiences, current concerns, education, and background.10

A systematic review from 2015 showed at least moderate levels of implicit bias for most healthcare providers.11 Healthcare providers may have an implicit bias against older adults due, in part, to the presumed increased frequency and complexity of providing care.12 Ageism in healthcare can have significant negative effects on the quality of life experienced by older adults.13,14 Implementation of effective interventions aimed at reducing or preventing ageism toward older adults, including addressing policies and laws, education, and intergenerational contact, support the delivery of age-friendly healthcare.14

Strategies using educational interventions across all levels of education have been shown to support empathy and mitigate prejudice and discrimination. Intergenerational contact interventions may be the most effective for reducing ageism against older people by fostering positive attitudes towards ageing, improving empathy between age groups, facilitating greater ease in being with older people, and decreasing younger persons’ anxiety about their own aging.8

Encouraging Empathy

Empathy is the ability to connect with another person’s emotions and to accurately perceive or understand their perspective. Empathy is the key to understanding What Matters to the patient and other members of the interprofessional team.15 Improved patient outcomes are reported in clinicians with higher levels of empathy.16,17

Habits of the Heart. Habits of the heart are those involving professional ethical and moral responsibilities, such as empathy, and are one of three apprenticeships of professional education (habits of the head, hands, and heart).18

Visual Art Instruction. A 2019 narrative review of visual art instruction in medical education identified five focus domains: observation and diagnosis, empathy, team building/communication, wellness/resilience, and cultural sensitivity.13 These focus-domains align with the provision of age-friendly healthcare and the application of the 4Ms. Incorporating health humanities into age-friendly healthcare learning experiences may enhance student preparation and provide opportunities to develop habits of the heart, such as empathy, to better serve older adults.

Evidence-based Initiatives. Evidence-based initiatives, such as the 4Ms framework—intended to enhance the quality of healthcare provided to older adults by explicitly supporting What Matters most—should be included in professional training, including exploration and assessment of their utility to develop habits of the heart.

We contend that the use of health humanities with application of the 4Ms framework may enhance development of habits of the heart in health sciences students and work to address ageism and promote empathic awareness. Following is a description of an activity conducted by our team to address this goal.

Storytelling Through Photographs: the Pilot Project

A visual-arts health humanities interprofessional education (IPE) activity was developed using the 4Ms framework through health professions students’ original photographs of the lived experience of older adults. The goals of the activity were to: (1) develop students’ awareness of the 4Ms framework for age-friendly healthcare; (2) promote students’ empathy toward older adults; (3) provide an opportunity for students to consider personal ageist thoughts and perceptions in a safe space.

This pilot project utilized education and intergenerational contact, specifically a variation of storytelling through photographs, to address the goals of the activity.19 The modality of photography was chosen for this project based on support for use of visual arts in enhancing empathy in health professions students, ease of submission, and effective use of participant time. This brief report includes a sample of the photographs used in the IPE activity, student photographers’ narratives of alignment with the 4Ms framework, and lessons learned from implementing the activity. The full description of the IPE activity is being reported separately.

Methods of Instruction

Volunteer student participants (n=33; mean age of 25.7 years; age range 21-45) were recruited from five graduate health professions programs at one university, including clinical psychology (n= 14), pharmacy (n=4), physician assistant (n=3), and physical therapy (n=12). Students were introduced to the age-friendly healthcare initiative and the 4Ms framework at the initial session and provided informed consent.

Students were instructed to take and submit an original digital photograph of the lived experience of an older adult and encouraged to take photographs outside of healthcare settings. A brief narrative reflection on why they took the photograph and how it demonstrated alignment with age-friendly care and the 4Ms accompanied each photograph. The students had four weeks from the initial session to submit the photograph and narrative. A selection of photographs was used in a group IPE activity six weeks after the introductory session.

Photographs in this report are included based on two criteria: (1) the subject(s) in the photographs provided signed consent for the use of the photographs; (2) the student photographer provided a narrative reflection.

Photos and Reflections

The following photographs include the complete reflections and identify the professional disciplines of the student photographers. The narratives reflect the student photographers’ perceived representation of the 4Ms, which are bolded. The authors provided the photograph titles.

Figure 1. Walking Through Life (Pharmacy)

“This picture means many things to me, it shows being healthy, Mobility, and love. Every day the subjects go for a walk around their yard and I think it’s a great picture to represent Mobility. The couple in the photograph have been together for 71 years and still make time to go for walks together.”

Figure 2. The Solver (Clinical Psychology)

“This is a photo of my grandmother working on a puzzle and I think it relates to Mentation (Mind). The activity requires her focus and provides a mental challenge to solve.”

Figure 3. The Swimmer (Physical Therapy)

“The individual represented in the photograph is a 94-year-old retired pediatrician. She attends the gym daily to swim and use the sauna and loves swimming and socializing with her friends at the pool. She always has a smile on her face and we talk each time we see each other. She is a joyous friend to have and I was genuinely shocked when I learned her age. She is everything I could hope to be at her age and so much more.”

Figure 4. The Hiker (Clinical Psychology)

“The Mobility “M” best represents my photo. The individual is physically active, as shown by her happily walking her dog outside on a trail. I would also argue that this activity relates to the Mentation (Mind) “M” by being a part of nature as a stimulating activity. That being said, the physical activity involved does seem to be the overarching symbol here.”

Figure 5. The Boxer (Physical Therapy)

“This photograph depicts a man in his 70s who enjoys boxing. Despite the progressive condition that limits his Mobility and strength, he has worked hard to maintain his range of motion and muscular endurance so that he can continue to perform activities of daily living without being completely dependent on others. One way he chooses to stay active every week is by attending boxing classes with his friends at LDBF Boxing, where he has been a proud Gladiator for many years. He takes Medications for his condition and continues to have limitations with balance, strength, and coordination. However, he is always alert and excited for the chance to box and put any frustrations onto the bag. This photograph represents the aspect of his physical fitness that is the most important to him: Mobility. Although he uses a rolling walker to get around and struggles with the loss of balance while walking, boxing allows him the support of the bag for balance while working on Mobility, endurance, power, and self-efficacy.”

Figure 6. The Teacher (Physical Therapy)

“I believe that Mobility is most represented because the subject described how teaching water aerobics has allowed her to be more active and live a more fulfilling life.”

Figure 7. Art Appreciation (Clinical Psychology)

“The photograph was taken at a book release event at the Black Art In America Museum, located in East Point, GA. Attendees were able to meet the authors of the book, “I Wish My Dad: The Power of Vulnerable Conversations between Fathers and Sons” and enjoy a Black art exhibition. The individual photographed engaged in conversation about the importance of mental health (Mentation (Mind)) in the black community with me after learning I am a doctoral student.”

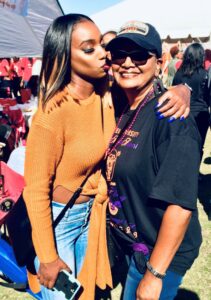

Figure 8. Generations (Clinical Psychology)

“The M present in the uploaded picture is What Matters. The picture shows a grandparent with his grandchild. It is an essential bond that has to be created using all the other Ms. It’s important to be healthy and mobile to spend time with a young one. In the picture, everyone seems happy and that clearly shows What Matters.”

Figure 9. Together (Physical Therapy)

“What Matters: In this photo, you can see that family togetherness matters. This is a photo of my mother, aunt, and grandmother. They are all together because my grandmother had her hip replaced. You can also see the cross necklace on my aunt, indicating that religious faith matters to her. Medication: It is very hard to see, but my grandmother is in a hospital gown in a hospital room, due to her recent THA. While Medication is not obvious, she was on medicine following her surgery. Mentation (Mind): This is not quite as obvious in the picture. You can tell, however, that each person in the photo was cognitively aware enough to either recognize that it was a photo and smile, as well as understand the verbal, to smile and look at the camera. My mother is also cognitively aware enough that she can work her phone to take a nice photo. Mobility: While my grandmother is sitting, you can see my mother and aunt are mobile enough to lean over and together to all fit into the photo frame. I think What Matters is most represented in this photo.”

Figure 10. Identity (Clinical Psychology)

“T is enjoying food from her favorite Vietnamese restaurant. What Matters to her the most is her Vietnamese identity. Ever since she left [Vietnam] in the 1970’s she has always tried to connect with the Vietnamese community in the US.”

Figure 11. Heart & Spirit (Clinical Psychology)

“I think this photo relates to the 4Ms because it shows Mentation (Mind). My dad (who is 66 years old) is with my brother (who is 44) and they were just goofing around and making jokes. My dad will play basketball and play pranks on my brother. My dad does not act like he is 66 years old. To me, because his heart and spirit are young and he stays active – his age is just a number and this picture shows that.”

Figure 12. Siblings (Clinical Psychology)

“As these siblings attend the wedding of a family member, they show us that even aging adults still desire to attend more upbeat and lively family functions. This demonstrates the Mobility aspect of the 4Ms Model, as they’ll tell anyone they meet that they swear by the law of inertia — just keep moving. They’re also endorsing the What Matters piece of the 4Ms model by continuing to engage in their social supports and getting out and about with people who matter to them.”

Figure 13. Sewing Joy (Physical Therapy)

“My grandmother moved in with us after my grandfather passed away in 2020. Throughout my lifetime, she has sewn beautiful quilts and blankets that she gifts to family and friends. It seemed like she was always working on a new project, and I have many fond memories of her teaching me how to sew and crochet. She first put down the needle when it became too taxing on her hands. However, she soon forgot how to sew as her Alzheimer’s disease (Mentation (Mind)) progressed. In the last few months, she tried it again and found herself able to sew. Now she has made quite a few smaller projects like towels and pillowcases that decorate our home. It brings joy to my entire family to see her enjoying her favorite hobby again.”

Figure 14. Best Friends (Clinical Psychology)

“I believe this photograph represents What Matters and Mobility as an aging adult. This is my dad and my son. They are the best of friends and my son loves my dad so much. Spending time being active with my son is something very important to my dad; they both love the outdoors and my dad is passing on his love of flowers, gardening, bugs, and animals to my son. Being mobile is another important aspect of aging for my dad. He is able to carry my son around his yard, take him on strolls through the neighborhood, and now he is walking and my dad can chase him around outside. He can lift him up and carry him on his shoulder and wrestle with him and do all the rough and tumble things little boys like to do. He prioritizes lifting weights and walking, gardening, and yard work as ways to stay fit into his 70s.”

Figure 15. The Farmer (Clinical Psychology)

“This photo highlights several of the 4Ms. First, it touches on What Matters. This picture displays someone who is proud of the business she created and the land she bought for herself. Her farm is something that began in her head and was translated into the world through her hard work. Mobility is another topic this photo hits on. Pictured is Farmer S on her tractor holding one of her favorite chickens. This highlights mobility because it shows her active living and participation in her everyday life. When she hosts parties, field trips, etc., she always cranks up and drives the tractor pulling the hay ride around the farm displaying the epitome of Mobility.”

Figure 16. Partners (Clinical Psychology)

“In this photograph, the representation of What Matters is the social support / spousal support. When asked the most important part of aging, the couple identify each other as What Matters most. Due to a recent fall that the wife had during Covid-19, this prevented her from a lot of activities; however, with the support of her very active husband, her recovery has been successful. Although both are 80 y/o neither has ambulation issues and limited Medication use. They were pleasant and happy with their current lifestyle. The photograph represents healthy aging and alignment to Mobility, What Matters, and Mentation (Mind).”

Figure 17. Little Moments (Physical Therapy)

“In this picture with my sister and grandmother, Mobility, Mentation (Mind), and things that Matter are most important. They were able to enjoy each other’s company at Mercer University’s homecoming a few years ago. My Grandmother enjoys the little moments! She always states that these are the moments that Matter Most. By using the 4 M’s, What Mattered most is spending time with her friends and family at the game, the ability to move around freely and without assistance, and the emotional and mental joy she received because of it.”

Figure 18. The Active Exerciser (Physical Therapy)

“This photo captures P in one of her favorite places and most-frequented places: her local country club. At 80 years old, P is one of the most active and energetic people I know. She does yoga, HIIT classes, swims laps, plays pickleball and tennis, and works out with a personal trainer. Sometimes she spends all day at the country club taking different fitness classes, and enjoying lunch or dinner with friends. Before her husband died, P used to come to work out at the country club with her husband. Since his passing, she has leaned more into the social and community aspects of the country club. I believe this photograph represents What Matters to P, in addition to Mobility and Mentation (Mind).”

Figure 19. The Builder (Clinical Psychology)

“This photo is of BP doing one of the things he loves most and grew up doing as a kid: building. After spending a year in rehabilitation for his back surgery, he is finally almost fully off of his pain Medication and able to walk and lift (Mobility). For someone who was always physically fit, being on bed rest and then requiring lots of support to heal did a number on his mental health. Now he is grateful to be able to walk, take care of himself, and even remodel his fireplace on his own.”

Figure 20. Waterfall (Physician Assistant)

This picture fully encompasses Mobility. She is still able to hike and reach beautiful sites such as the waterfall behind. What Matters to her is being able to maintain her Mobility and be in nature with her family.

Discussion

The inclusion of health humanities in health professions education supports and enhances an understanding of the human condition, fosters the development of habits of heart, and has a direct correlation to skills needed in clinical practice.20 The activity referenced in this report used visual art, reflection, interprofessional education, and intergenerational contact to develop students’ understanding of the IHI age-friendly 4Ms framework, promote empathy, and allow for consideration of ageism in a safe space. The use of narrative allowed students to reflect on a photograph of an older adult engaging in their lived experience in the context of the 4Ms.

Pedagogical approaches for integrating health humanities into professional health sciences curricula include narrative, visual art, poetry, critical research and perspectives, film, and literature.21

- Narrative includes “sharing of narratives, close reading of literature, and reflective writing”21(p887) and supports the ability “to listen for story within the therapeutic relationship and to facilitate patient-centered care”21(p887)

- Visual art can be integrated into curricula to develop “visual acuity, visual literacy, and observation skills beyond simple movement analysis, toward seeing individuals more holistically.”21(p887)

In this project, narratives provide insight into the meaning of the photograph to the photographer and an avenue to share the story with others. Visual art was used to capture the holistic lived experience of older adults.

The 4Ms in This Context

Analysis of how the 4Ms were represented in the photographic images in this project shows Mobility (n=13) was most commonly cited in narratives of the 20 photographs shown, followed by What Matters (n=10), Mentation (Mind) (n=9), and Medication (n=4). A single 4Ms category was reported in eight photos, two 4Ms in seven photos, three 4Ms in two photos, and two with all 4Ms in the narrative. One photograph narrative did not identify 4Ms categories and inferred Mobility (Figure 3.)

Three considerations may have influenced the distribution of the 4Ms represented in the photographs. The first is the health professions discipline of the photographer. This voluntary activity included students enrolled in clinical psychology, pharmacy, physician assistant, and physical therapy programs. Profession-specific implicit biases may have influenced the framing of the photographs and the narrative interpretations. The relationship of the photographer to the subject may have also influenced the 4Ms narrative. Family members are captured in 10 of the images shown. The personal connection to the subject may have influenced the narrative reflection of what matters to the photographer. The final consideration is that students were asked to take photographs outside of the healthcare experience. The authors believed that this stipulation would support respect for the lived experiences of older adults beyond healthcare interactions and provide students an opportunity to capture and reflect on What Matters for a moment in time. Students found it challenging to categorize their photographs by a single 4Ms category. This is a positive finding, as the implementation of the 4Ms framework is built around a multifaceted approach and not siloed.

The 4Ms Approach to Combating Ageism

This activity addressed ageism through the application of best-practice strategies including education using the age-friendly healthcare framework, and intergenerational contact using storytelling through pictures of older adults. Educational and intergenerational activities are two of the three strategies recommended by the WHO to reduce Ageism.8 Effective and best-practice intergenerational activities include use of storytelling, promoting empathy, intergenerational cooperation, development of friendships, and documentation of the process.8,19

Ageism is a global problem that exists at societal, organizational, and individual levels. In healthcare, ageism occurs at the institutional level when organizations perpetuate it through actions and policies.22 At an individual level it may manifest in an interpersonal context during social or formal healthcare interactions, with negative outcomes for older adults.13

Efforts to reduce or prevent ageism should occur at societal and individual levels. Educational and intergenerational contact have been reported as effective interventions to combat ageism. Interventions combining educational and intergenerational contact have been shown to have a greater effect on attitudes (empathy) toward older adults.14

Health sciences education appears to be an optimal time to address ageism, as students are developing their professional identities and encountering older adults during experiential education. Like clinical skills, thinking and acting in a non-ageist way can be developed through practice. Change can occur through listening to personal stories, reading research and narrative, engaging in advocacy efforts, and actively correcting ageist stereotypes, jokes, and discrimination.22

Photograph vs. Stereotype

In this project, the photographs provided a contrast to stereotypical ageist views of older persons. Ageist stereotypes have been reported to include assumed physical and mental illness, cognitive impairment, weakness, fragility, dependence, isolation, inability to perform activities, and being short-tempered or irritable.23 However, the narratives that accompanied some of the photographs of older adults engaging in their lived experiences may have reflected implicit bias. The lived experiences of the individuals captured in the photographs in the context of the 4Ms framework provide opportunities for reflection on the importance of the moments, and consideration of What Matters to the individuals.

Extrapolating to healthcare, we hope that students will remember these vivid images when recommending treatments or providing healthcare in the future. The impact on healthcare delivery to the subjects of the photographs was not a component of the activity; however, opportunities to use the narratives and photographs as foundational components of interprofessional case studies were identified by the authors.

The Figure 9 “Together” narrative addresses each of the 4Ms and is the only photograph taken in a healthcare setting. The narrative identifies opportunities for delivery of age-friendly care including attention to detail “the cross necklace…indicating religious faith matters” and availability of caregiver support.

The narrative for Figure 5 “The Boxer” identifies self-management activities for a man with an unidentified progressive health condition.

Knowing What Matters to the patient, family, and caregivers living with a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease (Figure 13. Sewing Joy) may support management strategies throughout the progression of the disease. The ability to visualize an individual engaging in their lived experience may enhance case-based learning activities.

Conclusion

The authors contend that viewing photographs like those in this activity may promote the delivery of age-friendly care using the 4Ms framework for older adults.

Future iterations of this activity may include providing clinical scenarios based on the individuals in the photographs to assess their impact on the clinical application of the 4Ms. Taking and viewing photographs of older adults like these may prove to be a useful way to develop an understanding of age-friendly care and mitigate ageist stereotypes. Viewing images of older adults outside of healthcare encounters may be an avenue to humanize the lived experiences of older adults. Including images outside of and within healthcare encounters in the context of the 4Ms may further prepare students to deliver age-friendly care.

The use of student-generated photography of older adults may be an effective way to integrate the humanities into health professions education and develop knowledge of age-friendly care and habits of the heart for the provision of quality care for older adults and their families.

References

- US Census Bureau. Older people projected to outnumber children for the first time in U.S. history. March 13, 2018. Available at: https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-releases/2018/cb18-41-population-projections.html. Accessed April 28, 2023.

- Bardach SH, Rowles GD. Geriatric education in the health professions: are we making progress? Gerontologist. 2012;52(5):607-618. doi:10.1093/geront/gns006

- Institute of Medicine. Retooling for an Aging America: Building the Health Care Workforce. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2008. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK215401/

- Institute for Healthcare Improvement: What is an Age-friendly Health System? IHI. Age Friendly Health Systems. Available at: http://www.ihi.org/Engage/Initiatives/Age-Friendly-Health-Systems/Pages/default.aspx. Accessed February 3, 202 3.

- World Health Organization. Questions and answers Ageing: Ageism. https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/ageing-ageism. Accessed February 23, 2023.

- Jönson H. We will be different! Ageism and the temporal construction of old age. 2013:53:198-204.

- World Health Organization. Global Report on Ageism: Executive Summary. 2021. Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240020504? Accessed November 13, 2024.

- World Health Organization. Global Campaign to Combat Ageism: Toolkit. 2021. Available at: https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/campaigns-and-initiatives/global-campaign-to-combat-ageism/global-campaign-to-combat-ageism—toolkit—en.pdf. Accessed November 13, 2024.

- American Psychological Association. Age and Socioeconomic Status. 2010. Available at: https://www.apa.org/pi/ses/resources/publications/age. Accessed February 3, 2023.

- Project Implicit. About Project Implicit. Available at: https://www.projectimplicit.net/. Accessed February 23, 2023.

- Fitzgerald C, Hurst S. Implicit bias in healthcare professionals: a systematic review. BMC Med Ethics. 2017;18(1). Doi:10.1186/s12910-017-0179-8

- Kearney N, Miller M, Paul J, Smith K. Oncology healthcare professionals’ attitudes toward elderly people. Ann Oncol. 2000 May;11(5):599-601. doi: 10.1023/a:1008327129699. PMID: 10907955.

- Ben-Harush A, Shiovitz-Ezra S, Doron I, et al. Ageism among physicians, nurses, and social workers: findings from a qualitative study. Eur J Ageing. 2016 Jun 28;14(1):39-48. doi: 10.1007/s10433-016-0389-9. PMID: 28804393; PMCID: PMC5550621

- Burnes D, Sheppard C, Henderson CR Jr, et al. Interventions to Reduce Ageism Against Older Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Am J Public Health. 2019 Aug;109(8):e1-e9. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2019.305123. Epub 2019 Jun 20. PMID: 31219720; PMCID: PMC6611108.

- Mukunda N, Moghbeli N, Rizzo A, Niepold S, Bassett B, DeLisser HM. Visual art instruction in medical education: a narrative review. Med Educ Online. 2019 Dec;24(1):1558657. doi: 10.1080/10872981.2018.1558657. PMID: 30810510; PMCID: PMC6394328.

- Davis MH. Empathy. In: Stets JE, Turner JH, eds. Handbooks of Sociology and Social Research. New York, NY: Springer; 2006:443-466.

- Everson N, Levett-Jones T, Pitt V. The impact of educational interventions on the empathic concern of health professional students: a literature review. Nurse Educ Pract. 2018;31:104-111. doi:10.1016/j.nepr.2018.05.015

- Colby A, Sullivan W. Formation of professionalism and purpose: perspectives from the preparation for the professions program. U St. Thomas LJ. 2008;5;404-426.

- World Health Organization. Connecting Generations: Planning And Implementing Interventions for Intergenerational Contact. 2023. Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240070264? Accessed November 13, 2024.

- Hojat M, Louis DZ, Maio V, Gonnella JS. Empathy and health care quality. Am J Med Qual. 2013;28(1):6-7. doi:10.1177/1062860612464731

- Blanton S, Greenfield BH, Jensen GM, et al. Can reading tolstoy make us better physical therapists? the role of the health humanities in physical therapy. Phys Ther. 2020;100(6):885-889. doi:10.1093/ptj/pzaa027

- Villines Z, Castiello L. What is ageism, and how does it affect health? Types, examples, and impact on health. Medical News Today. 2021. Available at: https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/ageism#examples. Accessed February 23, 2023.

- Rosell J, Vergés A, Torres Irribarra D, Flores K, Gómez M. Adaptation and psychometric characteristics of a scale to evaluate ageist stereotypes [published correction appears in Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2020 Nov – Dec;91:104248]. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2020;90:104179. doi:10.1016/j.archger.2020.104179

Member since 2019 | JM14274

Member since 2019 | JM14274

NO COMMENT